Wolff-Kishner Reduction

In this tutorial, I want to talk about the Wolff-Kishner reduction, a reaction in which we take a carbonyl compound, such as an aldehyde or ketone, and completely remove the carbonyl, reducing it all the way to the corresponding alkane. This reaction occurs in two distinct phases. In the first phase, we form the hydrazone intermediate, and in the second phase, we eliminate nitrogen, yielding the final product. Let’s go through each of these steps in more detail.

Hydrazone Formation

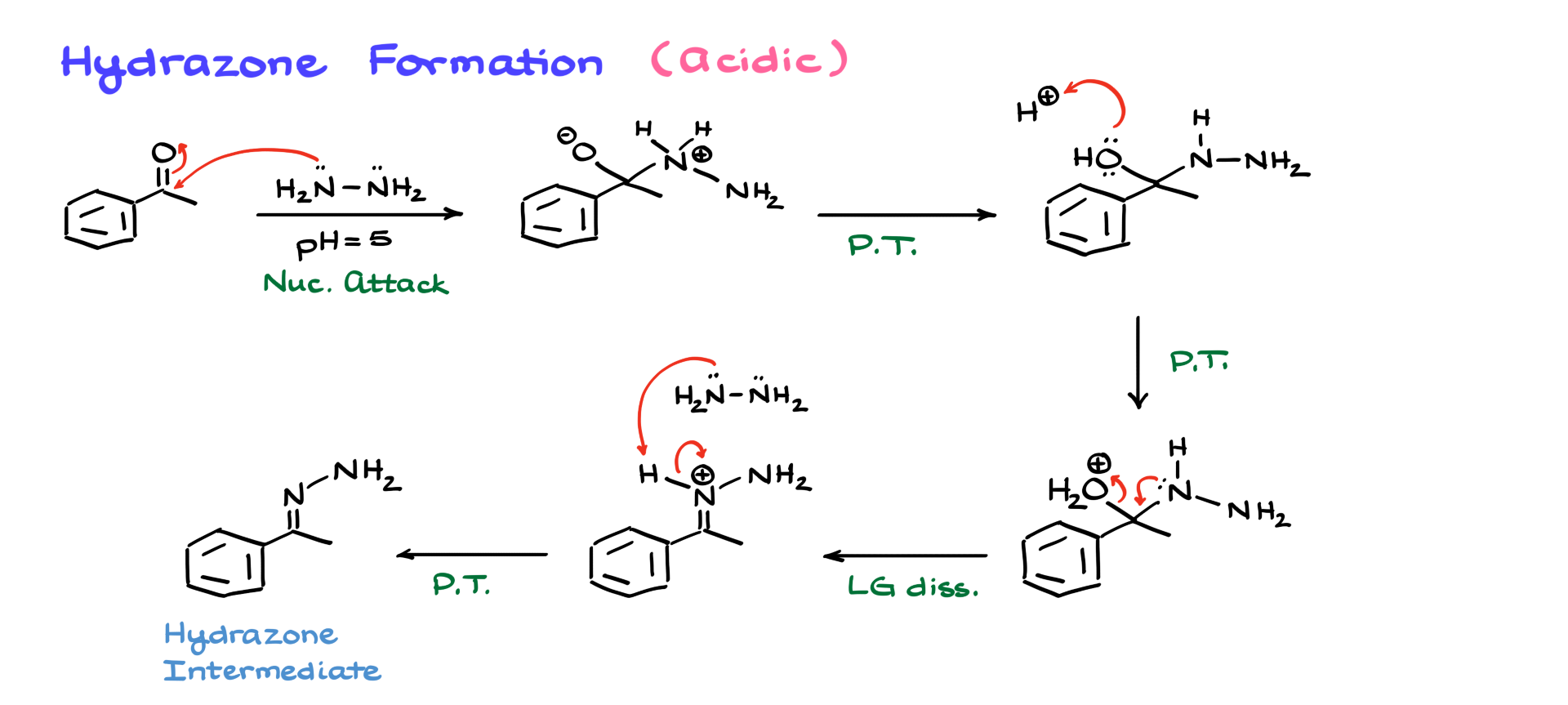

Naturally, we’ll begin with hydrazone formation. This reaction can take place under both acidic and basic conditions, so let’s first discuss the acidic conditions.

The first step in this mechanism involves a nucleophilic attack by hydrazine on the carbonyl. Hydrazine is a strong nucleophile, so there’s no need to protonate the carbonyl beforehand. As a result of this nucleophilic attack, we obtain a zwitterionic intermediate. From here, a couple of proton transfers occur, yielding a neutral intermediate, which we can technically refer to as a hemiaminal of sorts.

At this point, the acidic conditions come into play. We introduce H⁺ to protonate the OH group, converting it into a suitable leaving group. Then, nitrogen assists in expelling this leaving group, leading to an intermediate where we now have a protonated hydrazone. The last step in this stage is deprotonation to neutralize the molecule. To achieve this, we introduce another equivalent of hydrazine or any species with an electron pair to perform the final proton transfer, yielding the hydrazone intermediate. This is a fairly straightforward mechanism, similar to imine formation, except that instead of using a primary amine, we are using hydrazine.

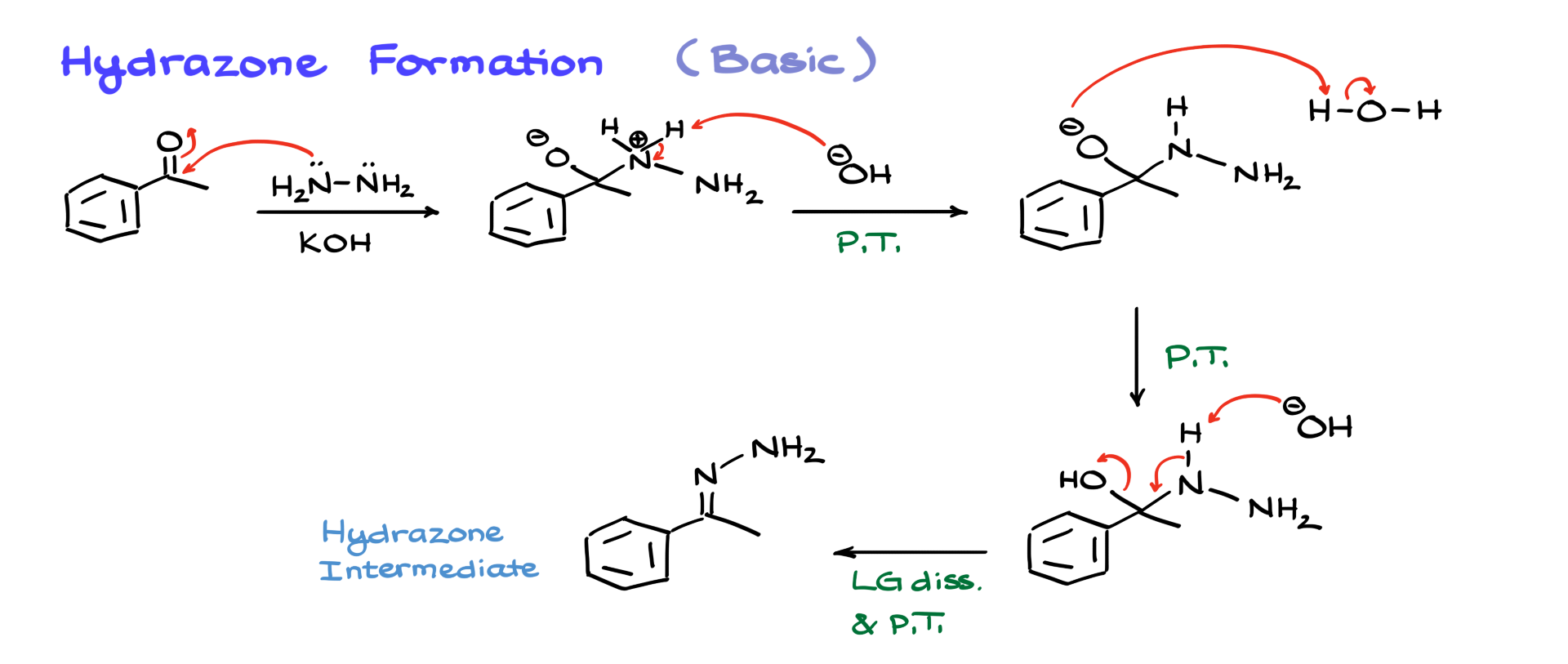

As I mentioned earlier, this reaction can also be conducted under basic conditions. In a basic medium, we start with the same reactants but introduce potassium hydroxide instead of maintaining a pH of 5. The initial step remains the same: hydrazine nucleophilically attacks the carbonyl. This leads to an intermediate, and at this stage, OH⁻ deprotonates the nitrogen, generating a negatively charged oxygen species. Water, which is present from previous steps, then protonates the negatively charged oxygen, restoring neutrality in the intermediate, similar to the acidic mechanism.

To remove the OH group in basic conditions, we introduce OH⁻ and proceed via an E2-style elimination. This leads to the formation of our final hydrazone intermediate. Now that we have the hydrazone, we can move on to the next step—eliminating nitrogen.

Elimination and Formation of an Alkane

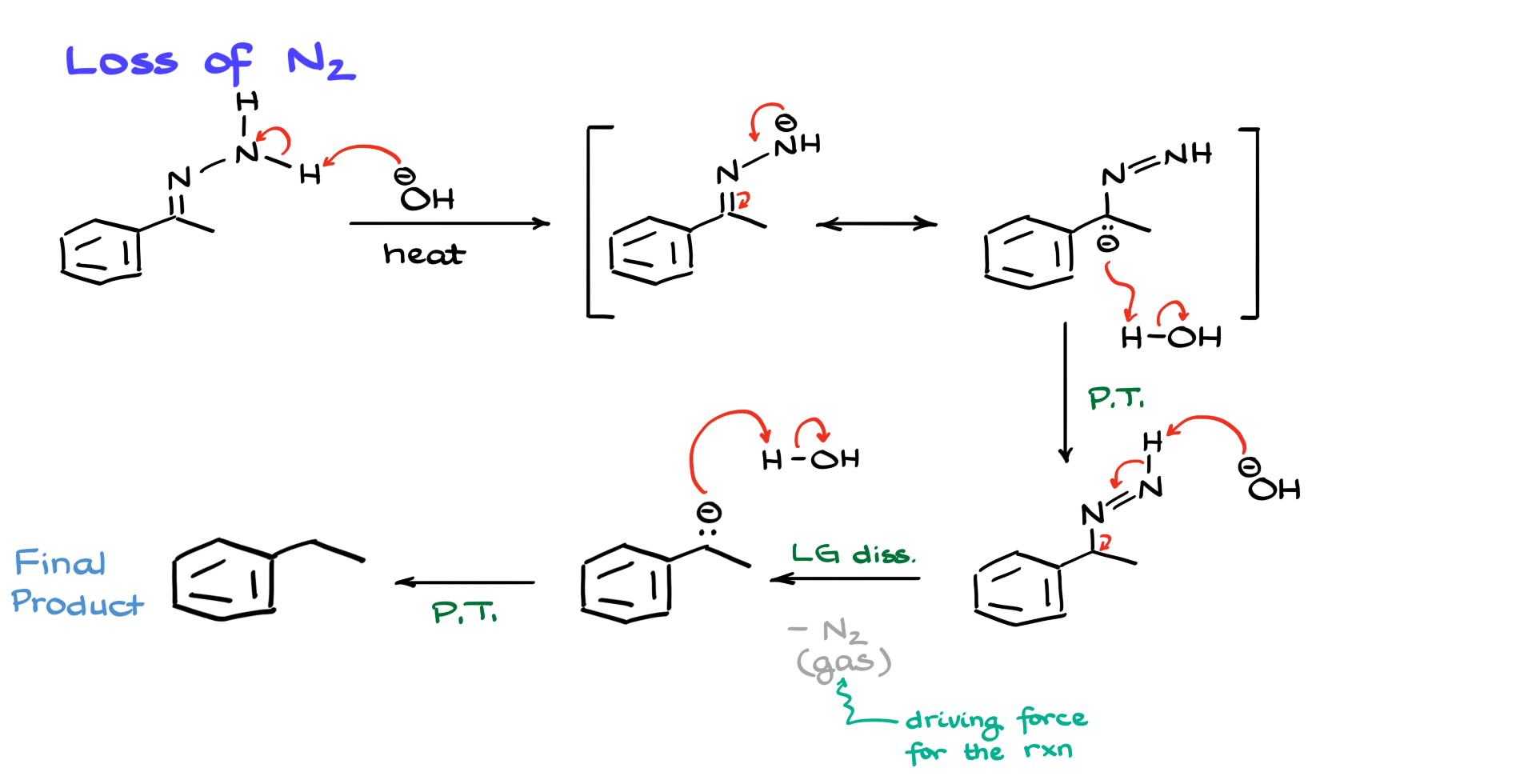

Once we have our hydrazone intermediate, we’ll proceed to the elimination part where we’ll get rid of nitrogen and make the final product−an alkane.

I’ll redraw the hydrazone, this time showing all the hydrogens, and introduce OH⁻ since the nitrogen elimination occurs under basic conditions. The first step here involves OH⁻ abstracting a proton from the hydrazone. Normally, a primary amine has a pKa around 36, but due to the presence of an allylic-like system, the pKa is somewhat lower—though not low enough to make this step highly favorable. The equilibrium constant for this reaction is not large, but the crucial aspect is that the resulting intermediate is stabilized by resonance. I can depict an alternative resonance structure by moving electrons, placing the negative charge on carbon.

This resonance contributor is important because it allows for reprotonation at that carbon position. Water in the medium provides the necessary proton, leading to the next intermediate. At this point, we are close to forming N₂ gas, which will eventually be eliminated. We introduce the base once more, and to simplify things, I’ll combine two steps by showing OH⁻ abstracting another proton and cascading electrons to form a negatively charged intermediate.

Research suggests that initially, a negative charge forms on nitrogen before nitrogen gas dissociates, but for simplicity, I’m combining these steps to avoid an excessively long mechanism. While forming the carbanion intermediate might seem unfavorable, it is not as unfavorable as one might think. The key driving force here is the evolution of nitrogen gas (N₂), which, once it escapes, makes this step effectively irreversible. Once the gas is gone, it’s gone. The only thing left is for the carbanion to pick up a proton from the surrounding environment. Water supplies this proton, yielding the final alkane product.

Overall, the reaction appears unfavorable until the very last step, where nitrogen gas is released and escapes. One of the biggest limitations of the original Wolff-Kishner reaction is the requirement for extremely high temperatures—typically 200–250°C. This is an impractically high temperature for many organic compounds, as they may decompose or simply evaporate along with the reaction mixture. Because of this, the original Wolff-Kishner procedure has a limited scope in terms of applicable molecules.

However, over the years, researchers have extensively studied this reaction, and methods have been developed to carry out the Wolff-Kishner reduction at room temperature with potentially good results. Another challenge with this reaction is that, in most cases, the hydrazone must be preformed, meaning it cannot be carried out as a single-pot reaction. Additionally, hydrazine, being a highly nucleophilic species, has low functional group tolerance, as it can react with many electrophilic functional groups, interfering with the intended transformation.

Despite its age—over a century old—the Wolff-Kishner reduction is still in use today. It has found applications in total synthesis and is even performed on a multi-pound scale in industry to produce certain important chemicals. Given the complexity of its mechanism, this reaction is a prime candidate for exam questions. Be sure to understand the mechanism well, including both the acidic and basic pathways and the final nitrogen elimination step.