Stereochemistry of Hydration and Hydrohalogenation

In this tutorial, I want to talk about the stereochemistry of hydrohalogenation and catalytic hydration reactions of alkenes. There are a few common tricks that instructors like to sneak into tests, and I want to make sure you’re fully prepared for anything that might come your way. So grab a cup of coffee and a notebook, and let’s work through some problems together!

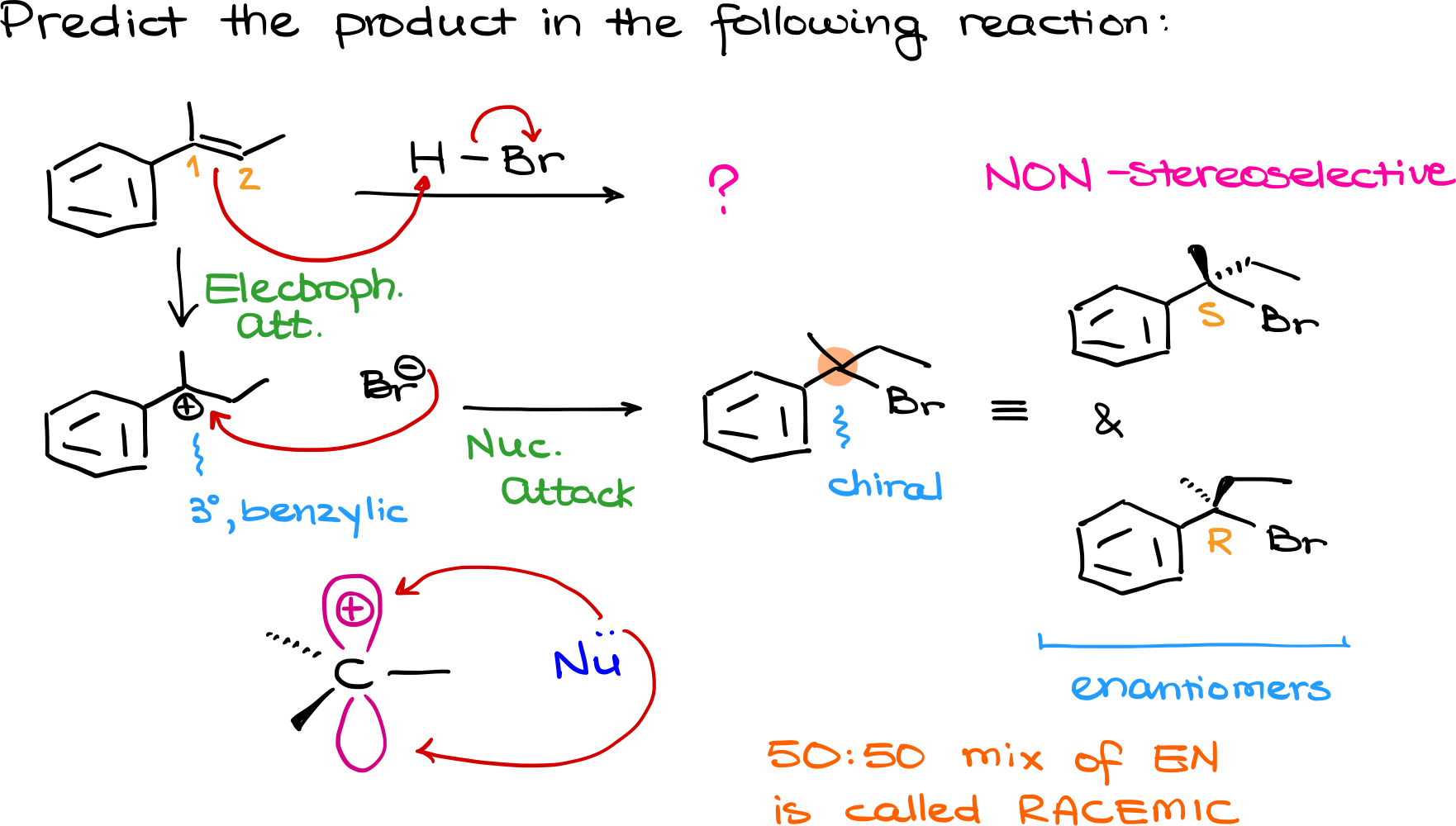

Our first question is to predict the product of this reaction. We know that hydrohalogenation begins with an electrophilic attack on the alkene. I’ll start by drawing the curved arrows, showing that the hydrogen from HBr adds to the double bond, leading to the formation of a carbocation intermediate.

Now, this step can potentially give two different carbocations—one at carbon 1 and another at carbon 2 if we number them this way. However, carbon 1 is tertiary, meaning it forms a tertiary carbocation, which is significantly more stable than a secondary carbocation. Even better, this particular tertiary carbocation is also benzylic, making it incredibly stable. Since we always prefer the most stable intermediate, I’ll go with the tertiary benzylic carbocation.

The next step is the nucleophilic attack by Br⁻. The bromine ion attacks the carbocation, forming our product. However, here’s something very important: the carbon where the bromine attached is chiral, meaning we don’t just get one product—we actually form a mixture of two different molecules. One product looks like this, while the other is its mirror image.

The stereochemical relationship between these two molecules is enantiomers. We can confirm this by assigning R/S stereochemistry to the chiral carbon. The molecule on top has the S configuration, while the one on the bottom has the R configuration. These two molecules are non-superimposable mirror images, making them enantiomers.

But why do we get both enantiomers? The reason lies in the carbocation intermediate. A carbocation has a trigonal planar geometry, meaning it is completely flat. Because of this, a nucleophile like Br⁻ can attack from either side of the molecule. Since there’s no factor in the reaction that makes one attack direction more favorable than the other, we end up with a 50-50 mixture of enantiomers. A 50-50 mixture of enantiomers is called a racemic mixture.

When Do We Get a Racemic Mixture?

The term racemic applies only when we have a 50-50 mixture of two enantiomers. If the reaction gives a 50-50 mixture of diastereomers, a chiral molecule plus an achiral molecule, or any other combination, it is not a racemic mixture.

Do We Always Get Enantiomers?

Actually, no! Let’s look at another case.

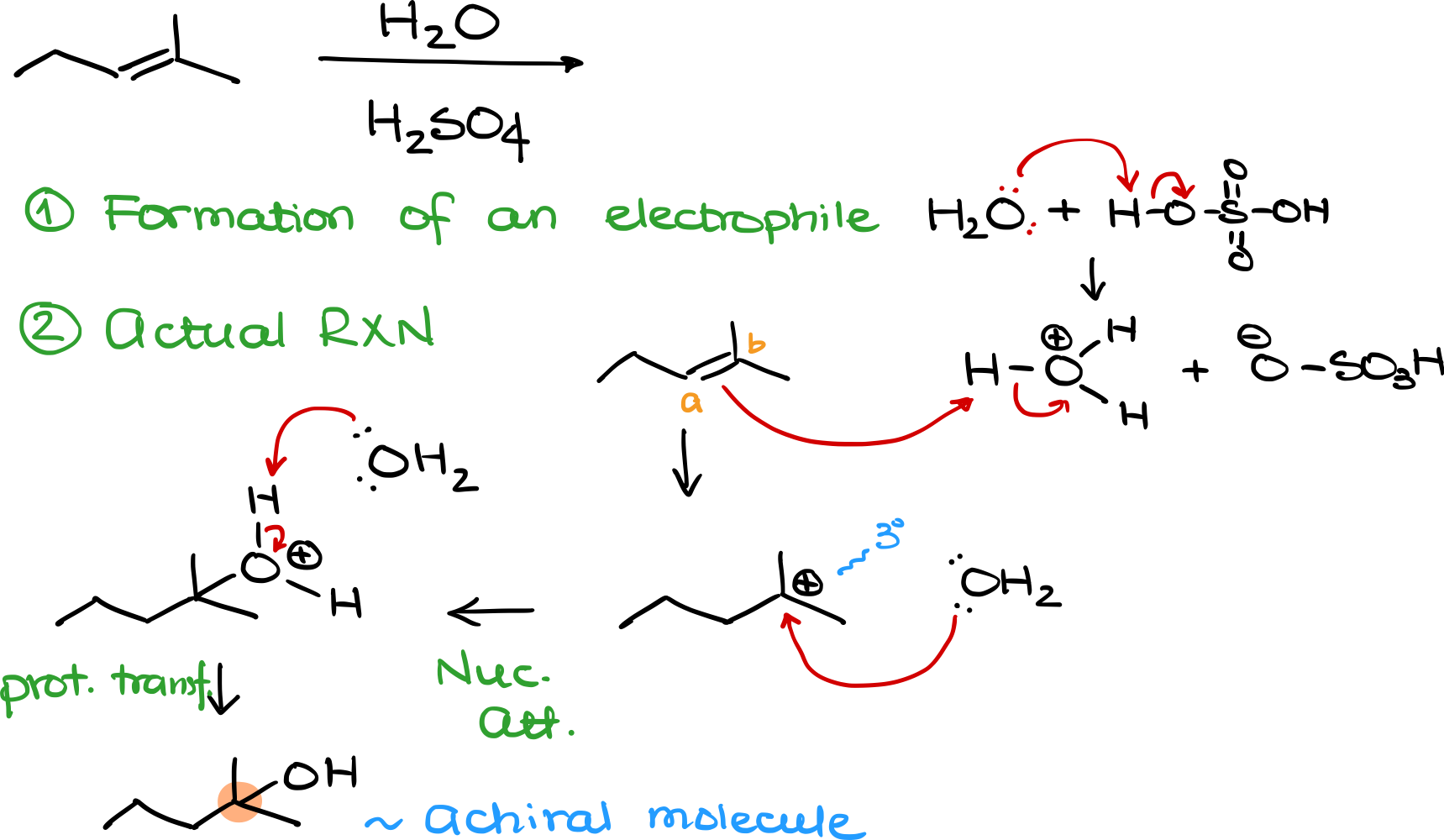

Consider this alkene reacting with acid-catalyzed hydration. In this reaction, water itself is not electrophilic enough, so the first step involves proton transfer between water (H₂O) and sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄). This gives us a hydronium ion (H₃O⁺) and the conjugate base HSO₄⁻.

Now, the actual reaction begins. The alkene reacts with H₃O⁺, which protonates the double bond, leading to carbocation formation. Again, there are two possible carbocations: one at carbon A (secondary) and one at carbon B (tertiary). Since tertiary carbocations are more stable, the positive charge goes on carbon B.

Next, water attacks the carbocation, forming a protonated intermediate. After deprotonation, we obtain the final alcohol product. However, if we examine the product, we see that the position where the OH attaches is not chiral. Since no new chiral center is created, we get only one product—not a pair of enantiomers.

What About Diastereomers?

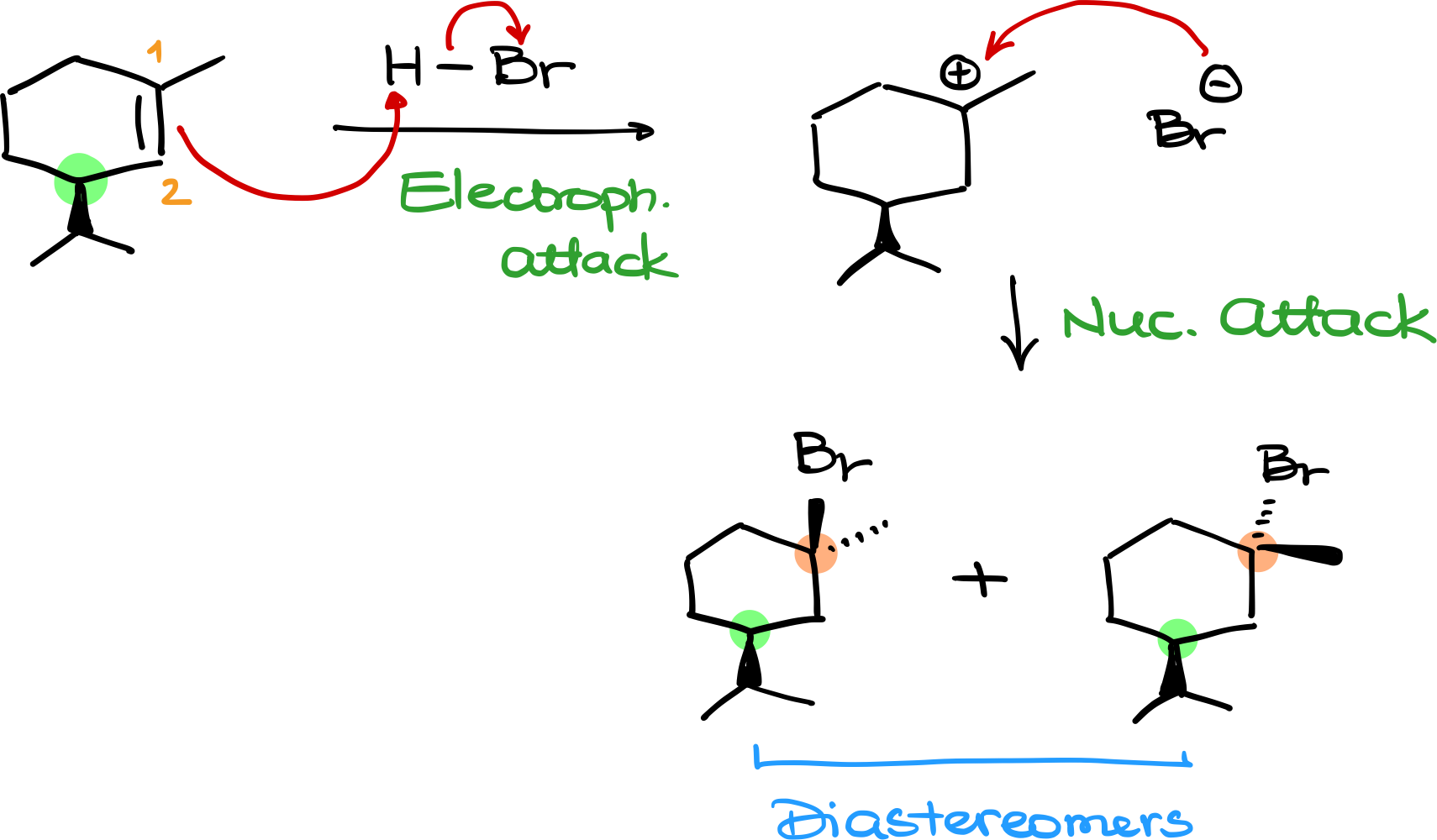

Let’s take another example. If we react a different alkene with HBr, the first step is again electrophilic attack, leading to the most stable carbocation intermediate. In this case, the most stable carbocation is tertiary.

Now, when Br⁻ attacks, it can do so from either face of the molecule—just like in our first example. However, here’s something new: this molecule already has a chiral center elsewhere in the structure. Since the nucleophile attack does not affect this existing chiral center, its stereochemistry remains unchanged.

This means that the two possible products are not enantiomers. Instead, they are diastereomers, since they differ at one chiral center while the other remains the same.

Key Takeaways:

1. If the reaction creates a single chiral center from a planar carbocation, you get a racemic mixture (50-50 of two enantiomers).

2. If no chiral center is created, you just get one product.

3. If an existing chiral center is present, the reaction can create diastereomers instead of enantiomers.

4. Never assume that these reactions always give enantiomers—carefully analyze the mechanism and stereochemistry!

So always make sure to carefully follow the reaction mechanism and analyze the stereochemistry of the products. Let me know in the comments if you’ve encountered any tricky stereochemistry questions—I’d love to hear your thoughts!