Oxyhalogenation of Alkenes

Oxyhalogenation of alkenes is a useful reaction for synthesizing halohydrins, adding a halide and a hydroxyl group to an alkene in a single step. Its mechanism closely resembles halogenation, and just like halogenation, it is stereospecific, yielding an anti-product where the OH and the halide are positioned on opposite sides of the molecule.

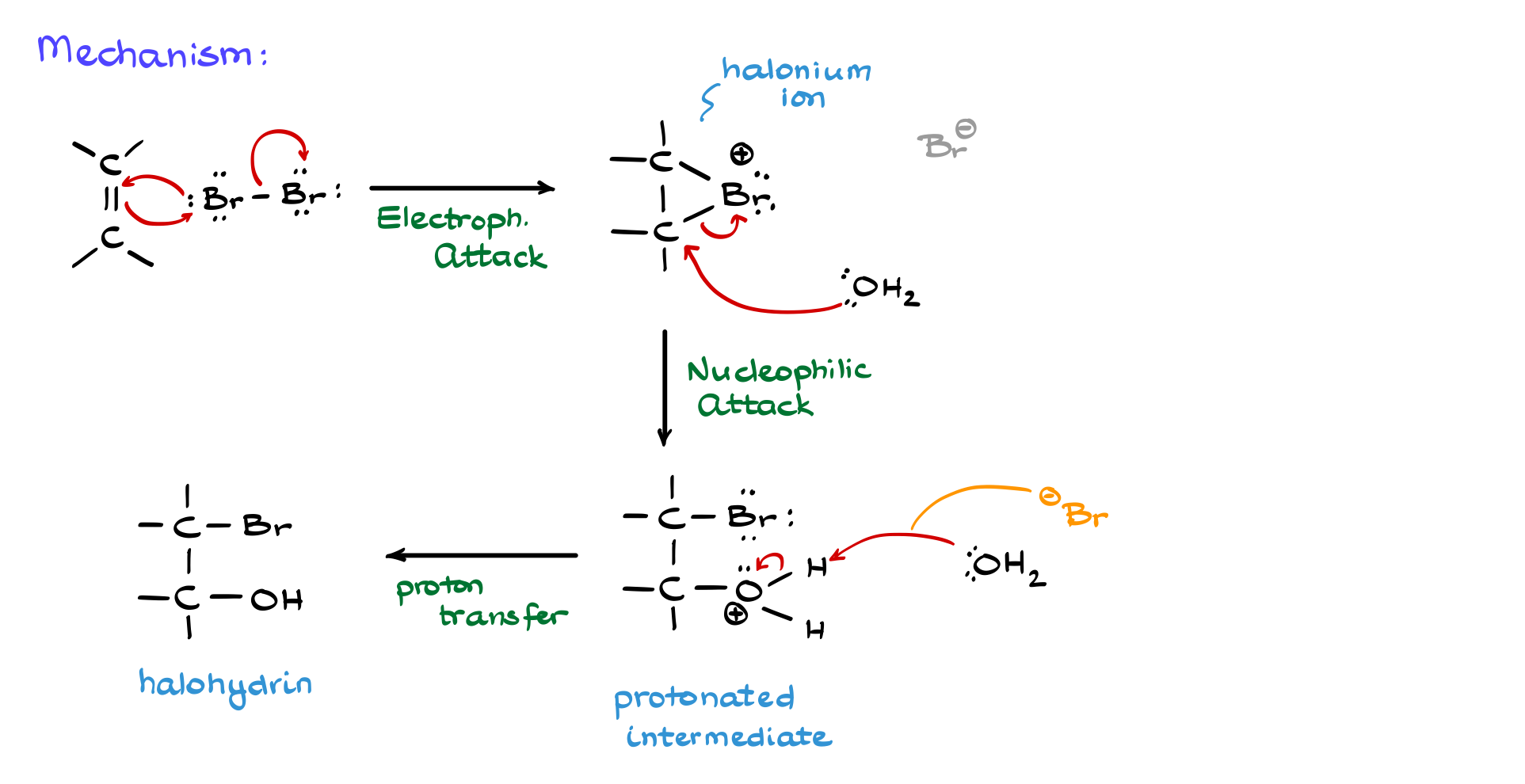

Mechanism of Oxyhalogenation of Alkenes

We begin with a generic alkene reacting with Br₂. In this case, the alkene acts as a nucleophile, donating electrons to bromine. This breaks the Br-Br bond, and the bromine atom that accepts the electron density simultaneously back-attacks one of the alkene’s carbons. This first step is identical to a standard halogenation reaction, forming a three-membered halonium ion, which is highly electrophilic. The next step is the nucleophilic attack, and here we have two potential nucleophiles: Br⁻ and water. However, because oxyhalogenation is performed in an aqueous medium with an excess of water, water is the dominant nucleophile.

You might wonder why water, a neutral molecule, outcompetes Br⁻, which is negatively charged and generally a stronger nucleophile. The answer lies in sheer probability. Since water is present in overwhelming excess, the likelihood of a water molecule being near the halonium ion is much greater than that of a Br⁻ ion. Consequently, water performs the nucleophilic attack, opening the halonium ion and forming a protonated intermediate.

The final step is deprotonation to neutralize the intermediate. Water, now acting as a base, removes a proton, yielding the final halohydrin product. Some textbooks and instructors may alternatively show Br⁻ performing this deprotonation. While this is statistically less likely (as water is more abundant and more basic than Br⁻), it is not entirely incorrect, as the coproduct of the reaction is HBr. Showing Br⁻ as the deprotonating species simply emphasizes the formation of HBr as a coproduct.

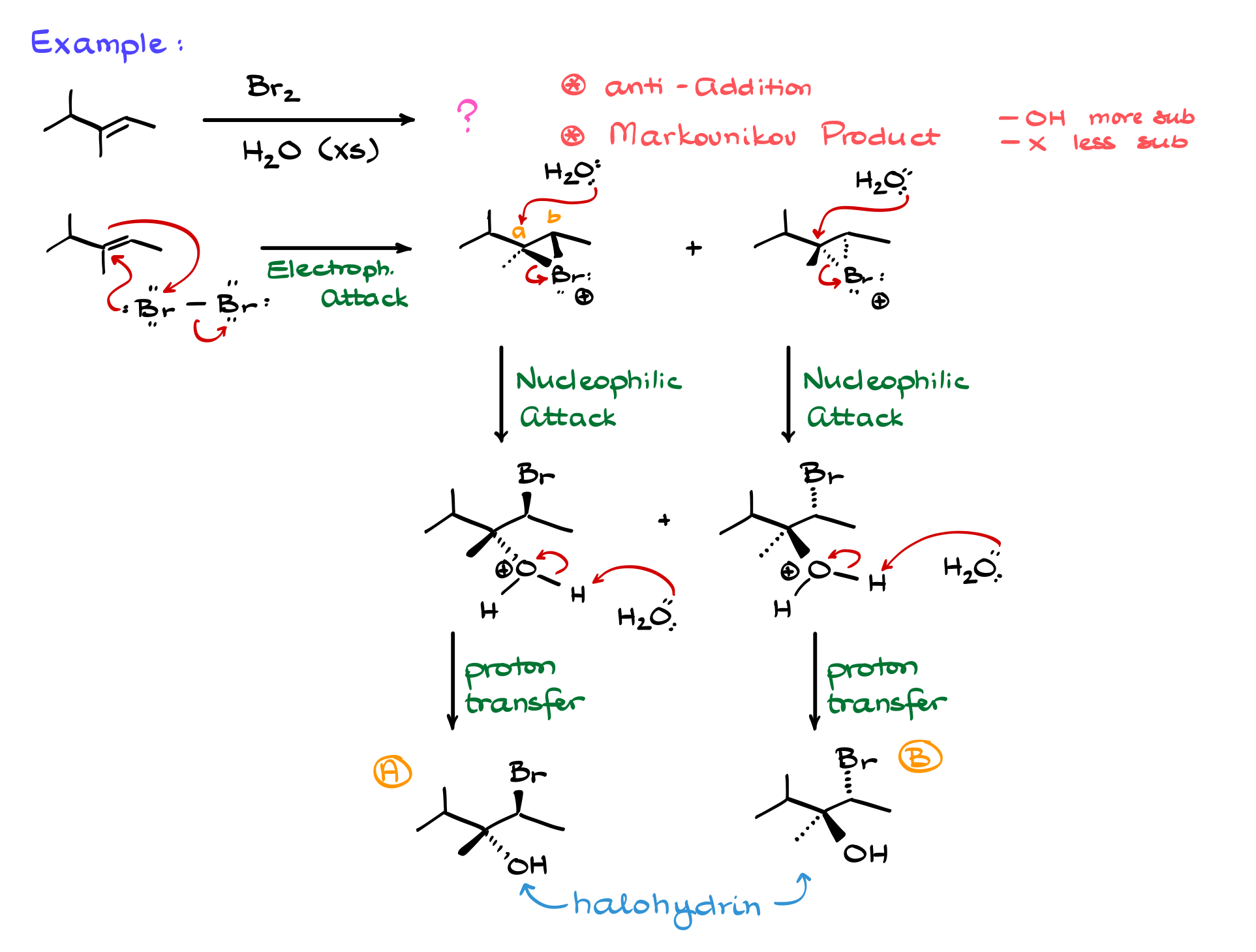

Example of Oxyhalogenation Reaction

Now that we understand the basic mechanism, let’s apply it to a real example. If we react an alkene with Br₂ in the presence of water, we must remember that water is in large excess—typically 10 to 50 times the amount of Br₂.

As in the generic mechanism, the first step is the electrophilic attack, where the alkene donates electrons to bromine, breaking the Br-Br bond. The resulting bromonium ion intermediate can form in two possible orientations: one where the bromine faces forward and one where it faces backward. Since Br⁻ is present only in trace amounts compared to water, we again see nucleophilic attack by water, which opens the bromonium ion at the more substituted carbon.

This regioselectivity is crucial. When a halonium ion forms, the more substituted carbon is more electrophilic due to partial carbocation character. As a result, nucleophiles (in this case, water) preferentially attack the more substituted carbon, just as they do in halogenation reactions. The resulting intermediate is then deprotonated, leading to the final halohydrin product.

Just like in halogenation, this reaction proceeds via strict anti-addition, meaning the OH and Br always end up on opposite sides of the molecule. No syn-addition occurs unless the molecule undergoes conformational changes after the reaction. The reaction is also highly regioselective, with the hydroxyl group attaching to the more substituted carbon and the halogen ending up on the less substituted carbon. Some sources describe this as following the Markovnikov rule, though it’s a slight stretch of the definition.

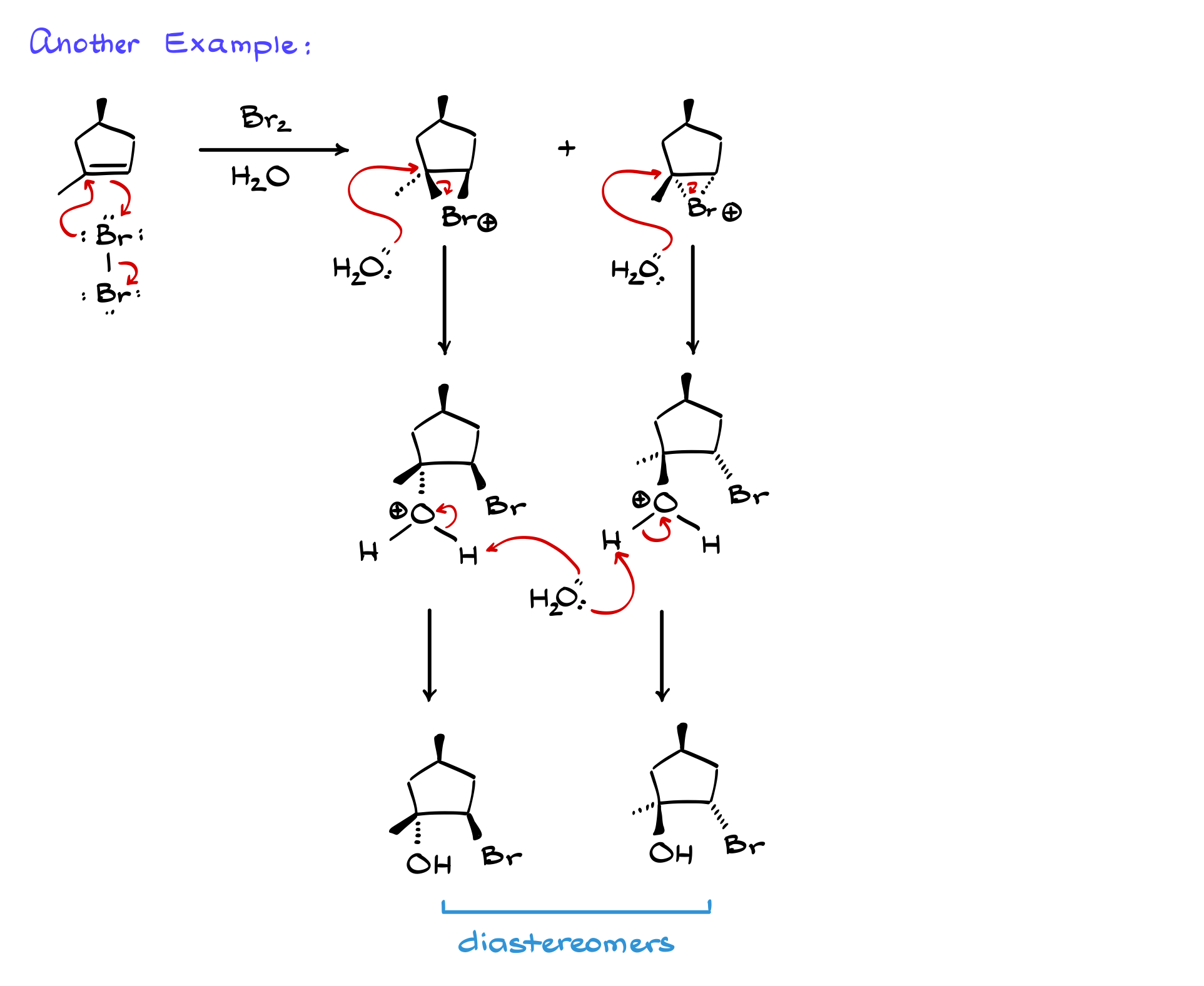

Another Example

Much like halogenation, oxyhalogenation doesn’t always yield a pair of enantiomers. Depending on the starting material, the products could be either enantiomers or diastereomers. For example, if we react a cyclic alkene with Br₂ in water, we may obtain a pair of diastereomers rather than enantiomers.

Let’s work through such a case. The first step remains the same—electrophilic attack by bromine, leading to two possible halonium ion intermediates. The second step is nucleophilic attack by water, which occurs at the more substituted carbon, opening the ring and forming the protonated intermediate. Finally, deprotonation yields the final halohydrin products, which in this case are diastereomers rather than enantiomers.

In summary, oxyhalogenation is a straightforward reaction that efficiently produces halohydrins, which are valuable intermediates for further synthesis. The two key principles to remember are:

- Regioselectivity – The OH attaches to the more substituted carbon, while the halide attaches to the less substituted carbon.

- Anti-addition – The OH and halide always end up on opposite sides of the molecule.

So, whether you’re working with simple alkenes or cyclic systems, paying attention to these two factors will help you correctly predict the product of an oxyhalogenation reaction!

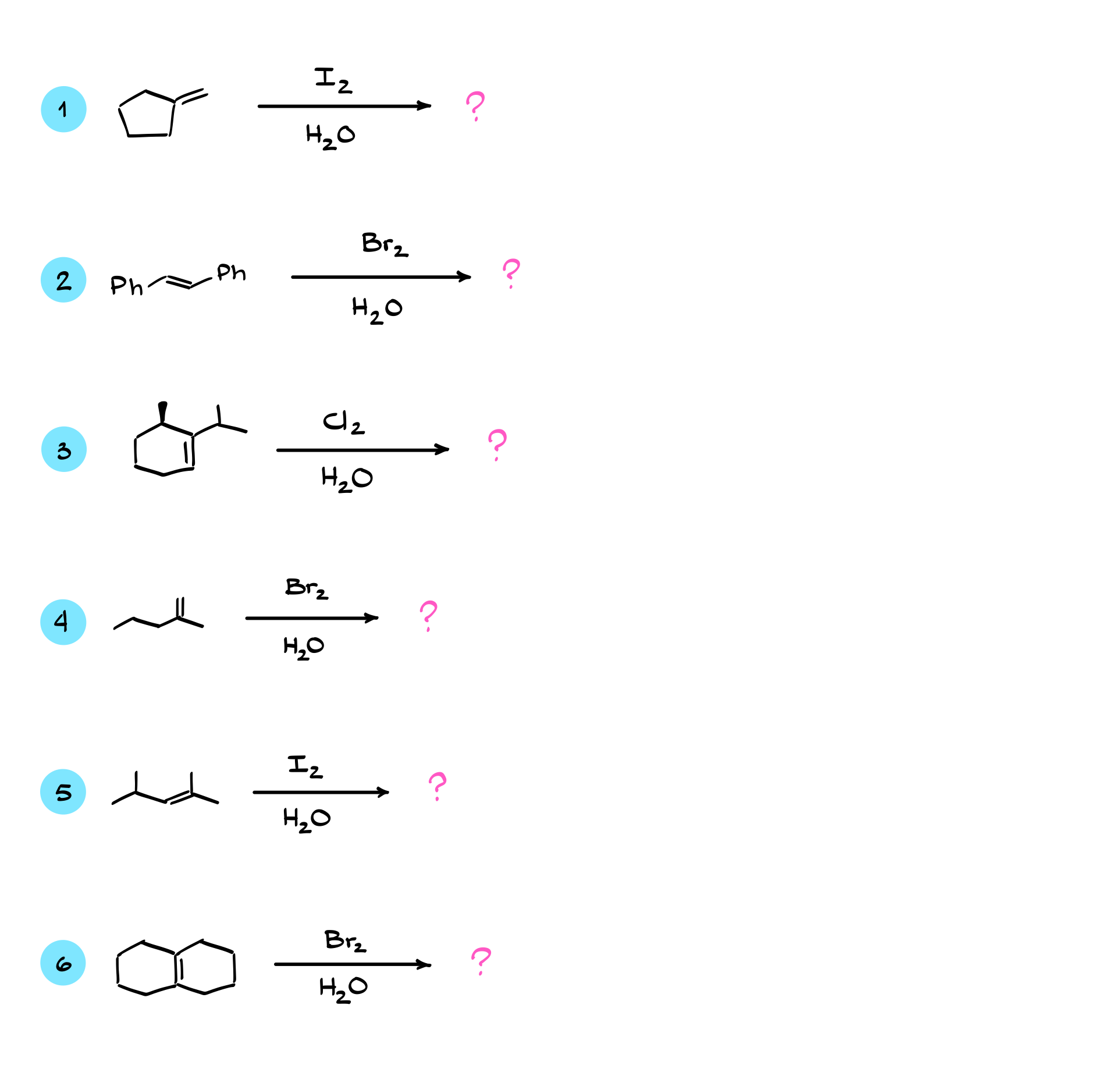

Practice Questions

Would you like to see the answers and check your work? Become a member today or login if you’re already a member and unlock all members-only content!