Nomenclature of Carboxylic Acids

In this tutorial, I want to talk about the nomenclature of carboxylic acids.

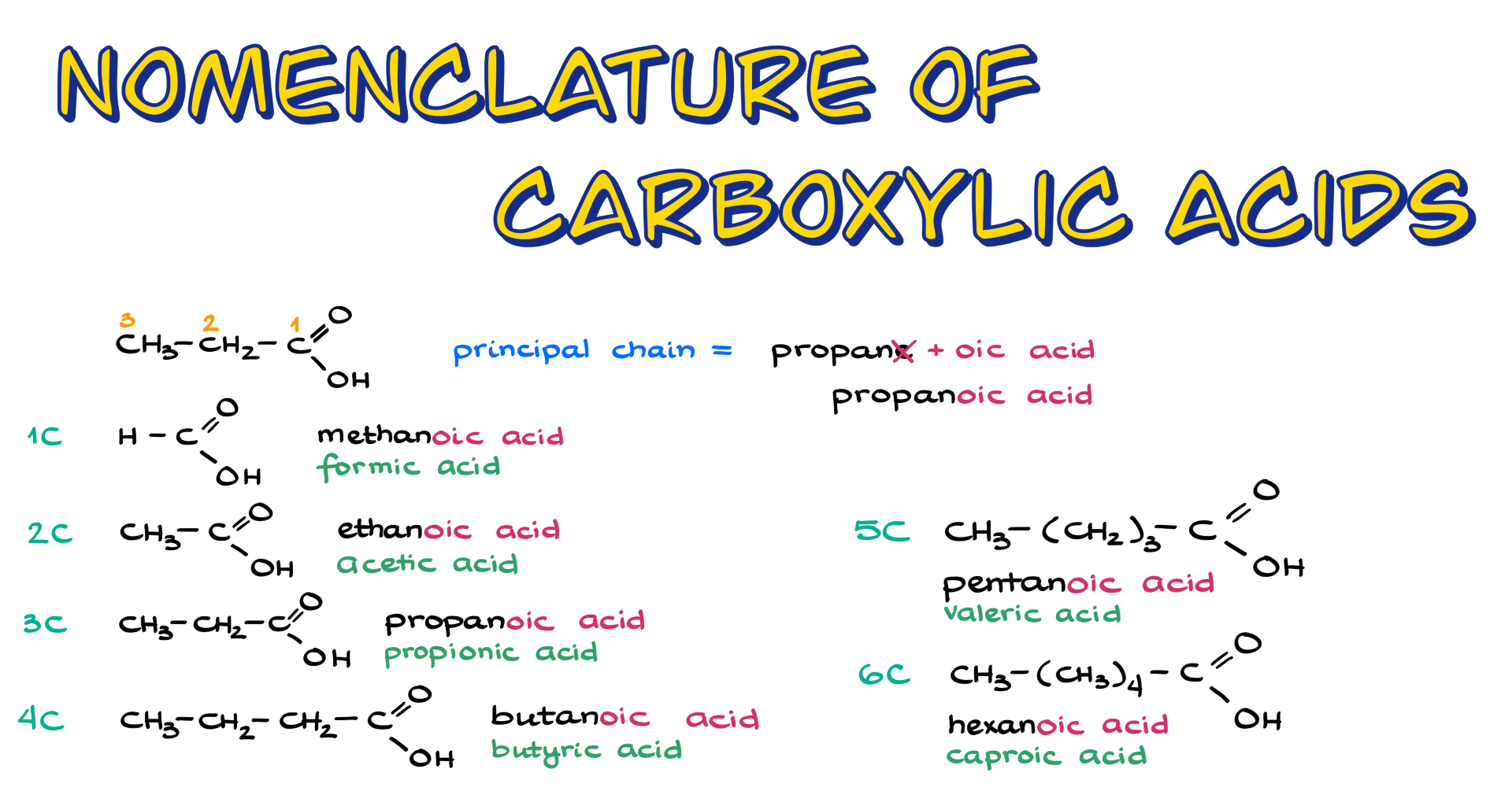

Let’s start by looking at this molecule over here. The molecule has one, two, three carbon atoms, which means that the parent name, or the principal chain, is going to be propane. To convert that into the name of a carboxylic acid, we remove the “-e” at the end and add “-oic acid.” That means the name of my molecule here is propanoic acid—pretty simple.

Following this pattern, if we have a molecule with only one carbon, that would be methanoic acid; with two carbons, it’s ethanoic acid; three carbons, as we just discussed, is propanoic acid; then we have butanoic acid, pentanoic acid, hexanoic acid, and so on. You get the idea.

Now, since carboxylic acids have been known for a long time, they also have common names, and some of these are used more frequently than their IUPAC names. For example, methanoic acid is commonly known as formic acid, while ethanoic acid is known as acetic acid. Propanoic acid is called propionic acid, and butanoic acid is known as butyric acid. For five-carbon carboxylic acids, pentanoic acid is sometimes referred to as valeric acid, though this name is less commonly used today. And for six carbons, we have caproic acid. However, you’re typically only responsible for memorizing the common names for the first four, and since the three- and four-carbon names are similar to their IUPAC counterparts, they’re easy to remember.

Substitutive Nomenclature

Of course, we won’t always be dealing with simple straight-chain carboxylic acids. So let’s discuss how substitutive nomenclature works.

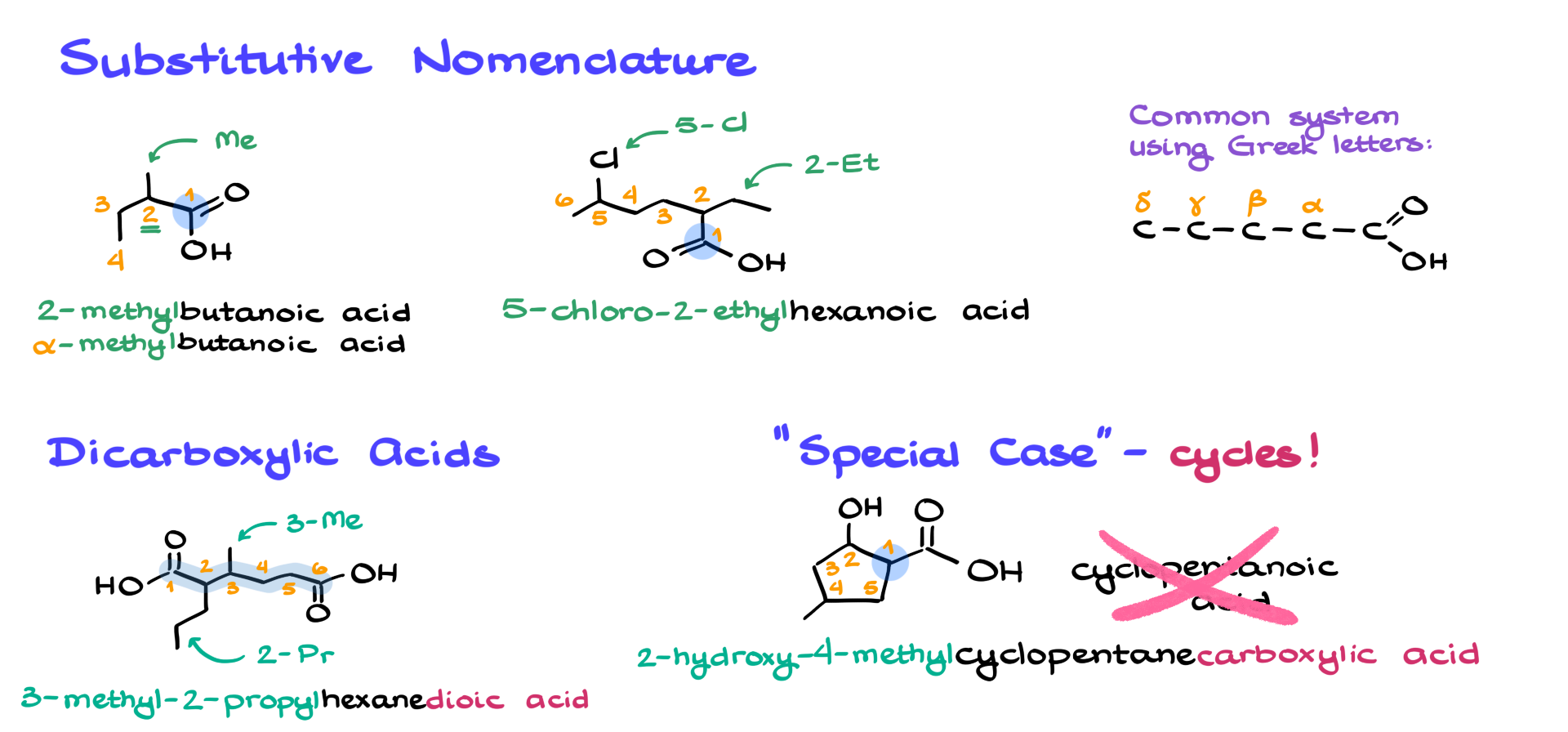

Let’s say I have this molecule here. The first thing to know about carboxylic acids is that the carboxyl functional group has the highest priority among all functional groups. That means numbering always starts from the carbon in the carboxyl group. From there, we determine the longest continuous chain, which in this case has four carbons. That means the parent name is butanoic acid. In this example, there’s a methyl group at the second carbon, so we need to indicate its presence in the name. The full name of this molecule is 2-methylbutanoic acid. Alternatively, if you prefer using the common name, you could call it 2-methylbutyric acid.

Now, let’s look at a slightly more complex example. Like before, the carboxylic acid carbon is position 1, and we find the longest continuous chain from that carbon, which in this case is six carbons long. That makes the parent name hexanoic acid. This molecule has two substituents: an ethyl group at carbon 2 and a chlorine at carbon 5. When naming molecules with multiple substituents, we alphabetize them. Since “chloro” comes before “ethyl” alphabetically, we write the name as 5-chloro-2-ethylhexanoic acid. Alphabetization is a common exam trick, so always double-check that part.

Occasionally, you’ll see the common system using Greek letters. In this system, the carboxyl carbon itself is not counted. Instead, the carbon adjacent to it is labeled as the alpha (α) position, the next as beta (β), then gamma (γ), delta (δ), and so on. Using this method, our 2-methylbutanoic acid could also be called α-methylbutanoic acid. However, Greek letters are typically only used when there’s a single substituent. If there are multiple substituents, it’s better to stick with numerical naming.

Now, what happens when we have dicarboxylic acids—molecules with two carboxyl functional groups? Take this molecule, for example. The principal chain is always the one that connects the carboxyl groups, regardless of its length. Here, the chain is six carbons long, so the parent name is hexanedioic acid. Since we have two carboxyl groups, we use “-dioic acid” instead of just “-oic acid” to indicate their presence. In this case, we also have substituents: a methyl group at carbon 3 and a propyl group at carbon 2. As always, we alphabetize them, so the full name is 3-methyl-2-propylhexanedioic acid.

There’s also a special case for cyclic carboxylic acids. If we have a five-membered ring with a carboxyl group attached, we don’t call it cyclopentanoic acid—such a name does not exist. Instead, we name it cyclopentanecarboxylic acid. Yes, it has a somewhat awkward ending, but that’s the correct IUPAC name, so we follow it. When numbering in a ring system, position 1 is not the carboxyl group itself but the carbon to which it is attached. If the ring has additional substituents—say, an OH group and a methyl group—then we number accordingly. For example, if the OH is at position 2 and the methyl is at position 4, the name of the molecule would be 2-hydroxy-4-methylcyclopentanecarboxylic acid. Quite a mouthful, I know!

Must-Know Common Names of Carboxylic Acids

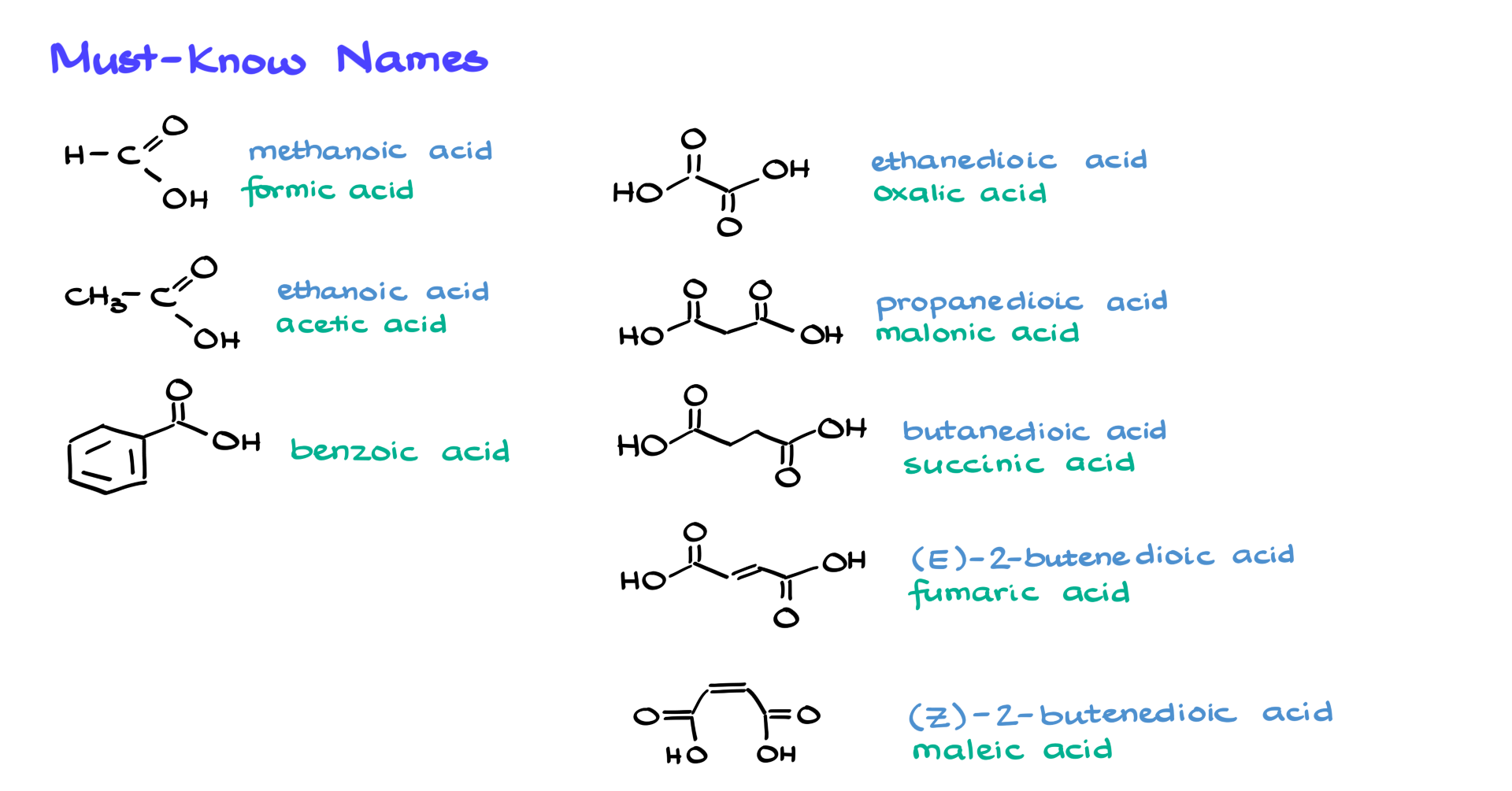

Finally, there are a few common names that you absolutely must know.

We’ve already covered methanoic acid (formic acid) and ethanoic acid (acetic acid), but in addition, you should be familiar with oxalic acid, malonic acid, and succinic acid when dealing with simple dicarboxylic acids. You’ll also encounter molecules with double bonds, such as fumaric acid, which appears in biochemical processes like the Krebs cycle, and malic acid, which is commonly used in organic synthesis.

One more essential name is benzoic acid. Unlike the other examples, benzoic acid does not have an alternative IUPAC name. There is no such thing as “benzene carboxylic acid”—it must be called benzoic acid. This is one of those common names that IUPAC has fully retained, so there’s no alternative.

And that covers everything you need to know about naming carboxylic acids!