Molecular Orbitals of the Conjugated Systems

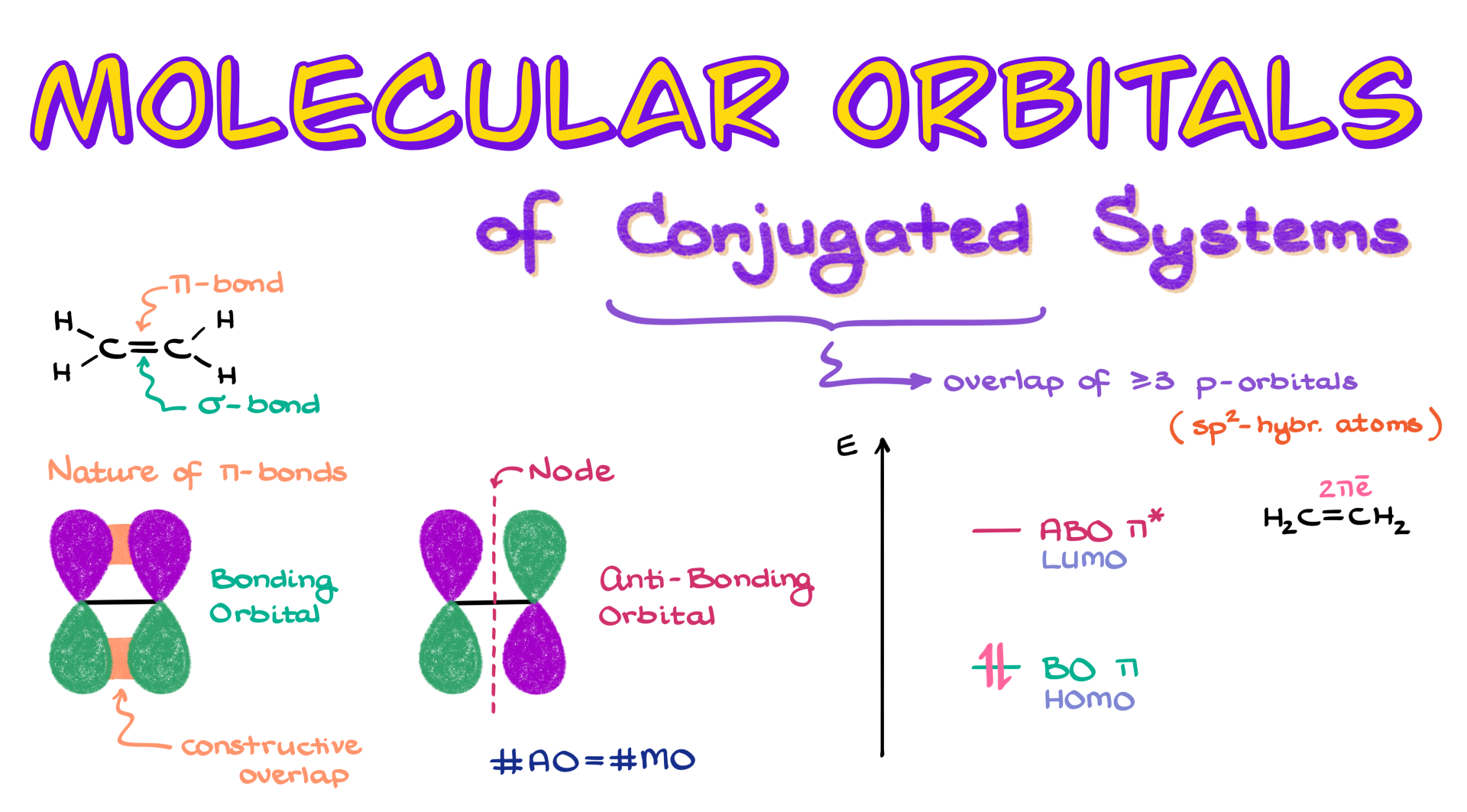

In this tutorial, I want to talk about the molecular orbitals of conjugated π systems. And if we’re going to dive into π systems, let’s quickly review the nature of the π bond.

Take the simplest example—a double bond in ethylene. That double bond consists of both a σ bond and a π bond. The π bond forms through the overlap of two atomic p orbitals. This overlap can be constructive, where both lobes of the p orbitals are in the same phase, or destructive when the orbitals are in opposite phases. In the destructive case, we get a node—a region with no overlap—which leads to an anti-bonding orbital. The original constructive overlap gives us the bonding orbital.

So, putting electrons into a bonding orbital promotes bond formation, but placing them into an anti-bonding orbital does the opposite—it destabilizes the bond. For every bonding orbital in a molecule, there’s always an “evil twin”—an anti-bonding orbital. These pairs always go hand-in-hand. And since the total number of molecular orbitals always equals the number of atomic orbitals, if we start with two p orbitals (like in a π bond), we end up with two molecular orbitals: one bonding and one anti-bonding.

Energetically, the bonding orbital lies lower than the anti-bonding one. So, electrons will always fill the lower-energy bonding orbital first because that’s the more stable option. Looking at ethylene again, we have two π electrons, and we place them in the bonding π orbital. In molecular orbital language, the highest occupied molecular orbital is called the HOMO, and the next available unoccupied orbital is the LUMO. These two—the HOMO and the LUMO—will differ depending on the specific molecule.

Examples of the Conjugated Systems

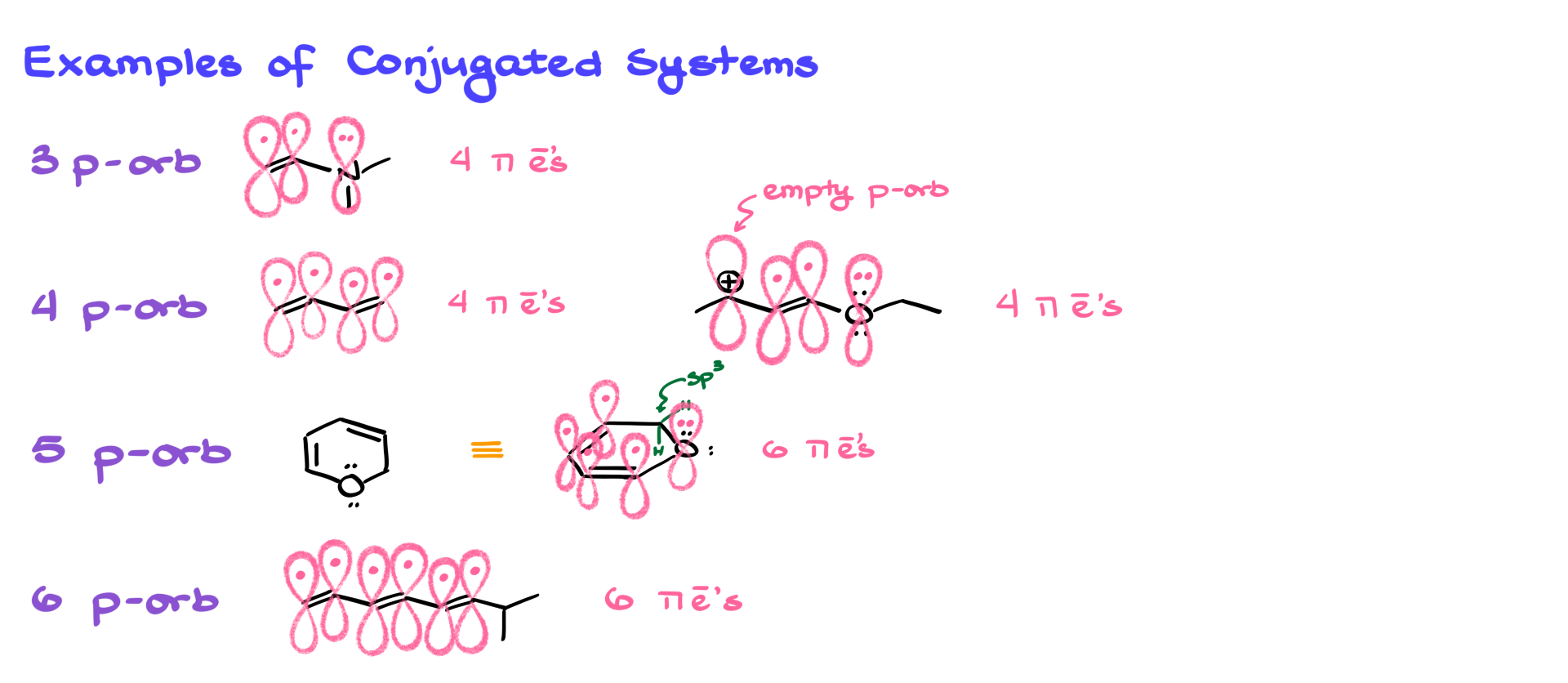

Now that we’ve reviewed the basics of a π bond, let’s move into conjugated π systems. A conjugated system involves the overlap of three or more π orbitals. So, something like ethylene doesn’t count—there’s only one isolated π bond. But as soon as we have a system where three or more π orbitals overlap, especially on sp² or sometimes sp hybridized atoms, then we’re in conjugated territory.

One simple example of a conjugated system is a three-p orbital system. Picture a setup where two orbitals come from a double bond, and a third orbital comes from a nitrogen atom holding a lone pair. The electron pair on the nitrogen is delocalized across the system, just like the π electrons of the double bond. Altogether, we have four delocalized π electrons in this three-p orbital system.

Another familiar example is butadiene—a four-p orbital system. It has four π electrons spread across the system. But conjugation doesn’t always involve just classic π bonds. It can include empty orbitals and lone pairs too. Imagine a molecule where you’ve got a π bond, an empty orbital, and a lone pair—still, that forms a conjugated system with four orbitals and four electrons.

We can even go cyclic. Picture a five-p orbital system, for example, with one non-contributing sp³ hybridized atom. In such a molecule, we end up with five p orbitals and six π electrons. Or take a six-p orbital system like a triene with all p orbitals lined up—that’s six orbitals, six π electrons.

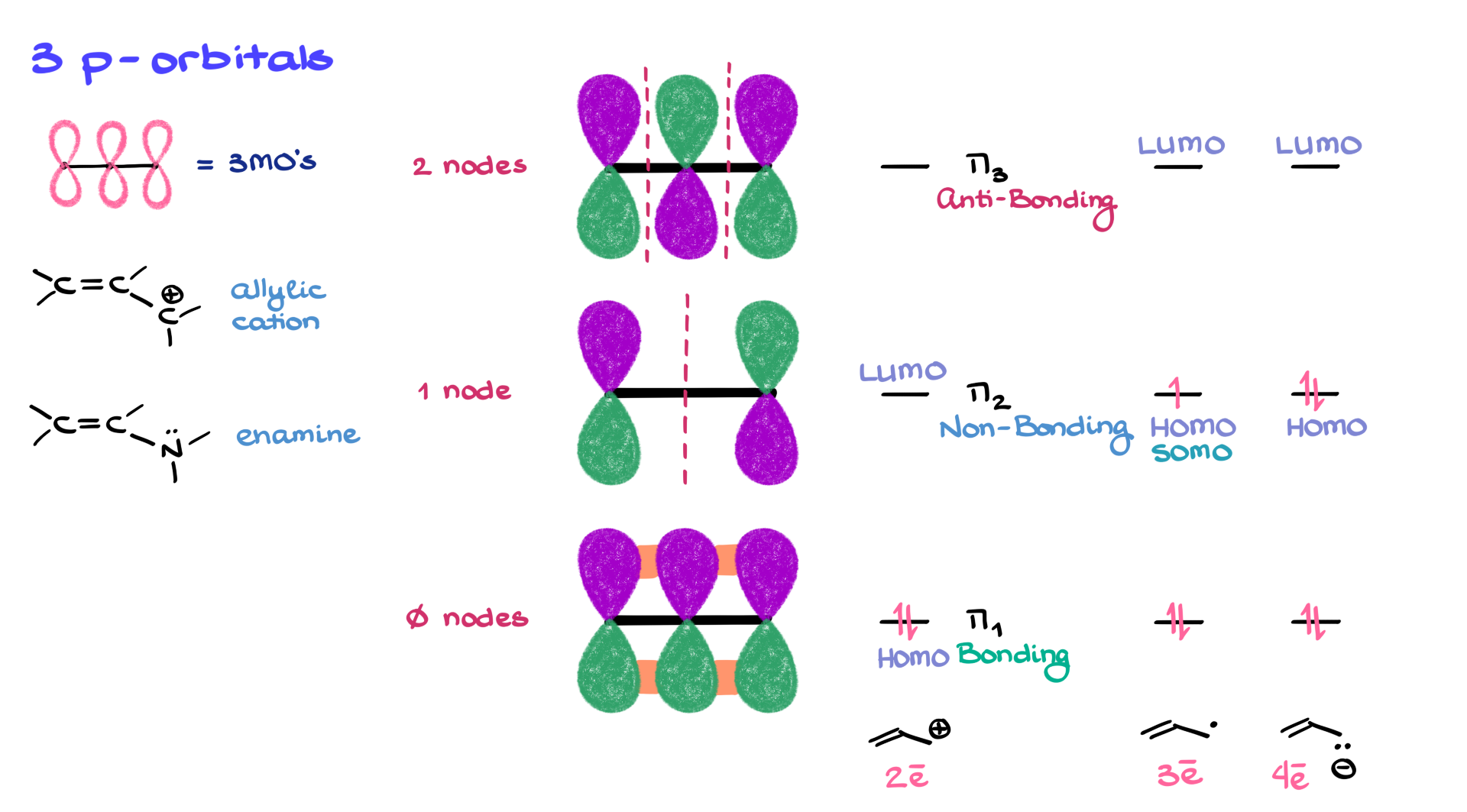

3 p-Orbital Systems

All of these conjugated systems described above follow the same orbital principles.

For instance, in a three-p orbital system like an allylic cation or an enamine, you’re bringing in three atomic orbitals, which gives you three molecular orbitals. The lowest energy one (π₁) has no nodes and features all orbitals in phase—this is a bonding orbital. The next (π₂) introduces a node right in the middle—so the central atom essentially gets canceled out. This orbital ends up being non-bonding, since the neighboring atoms can’t interact across that central node. Then the highest energy orbital (π₃) has two nodes and destructive overlaps—clearly anti-bonding.

Now let’s talk electron population. Take an allylic cation with just two π electrons. They go straight into the lowest orbital—π₁—making that the HOMO and π₂ the LUMO. Now, switch to an allylic radical—three electrons total. Two go into π₁, and one goes into π₂. That makes π₂ the HOMO (actually a singly occupied molecular orbital—SOMO), and π₃ becomes the LUMO. Add another electron for an allylic anion, and now we have two in π₁ and two in π₂. π₂ stays the HOMO, and π₃ is still the LUMO.

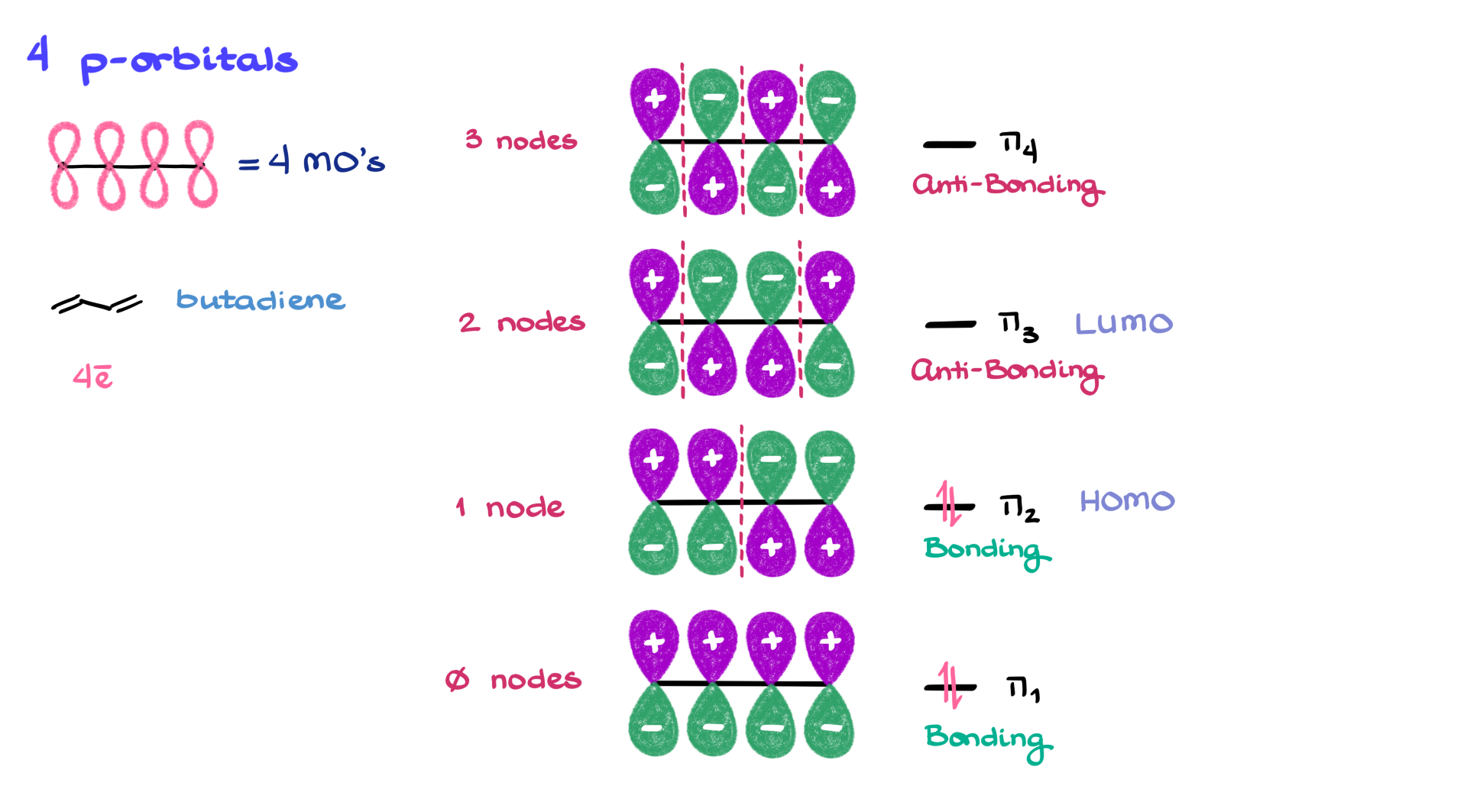

4 p-Orbital Systems

Moving to a four-p orbital system, like butadiene, we generate four molecular orbitals. π₁ has all orbitals in phase—bonding. π₂ introduces one node, but still has more constructive overlaps than destructive ones, so it’s also bonding. π₃, with two nodes, has more destructive interactions—making it anti-bonding. And π₄, with three nodes, is purely anti-bonding. Since there are four π electrons in butadiene, they go two in π₁ and two in π₂. That makes π₂ the HOMO and π₃ the LUMO. One note here: only systems with an odd number of orbitals will have a non-bonding orbital. Even-numbered systems have clear splits between bonding and anti-bonding orbitals.

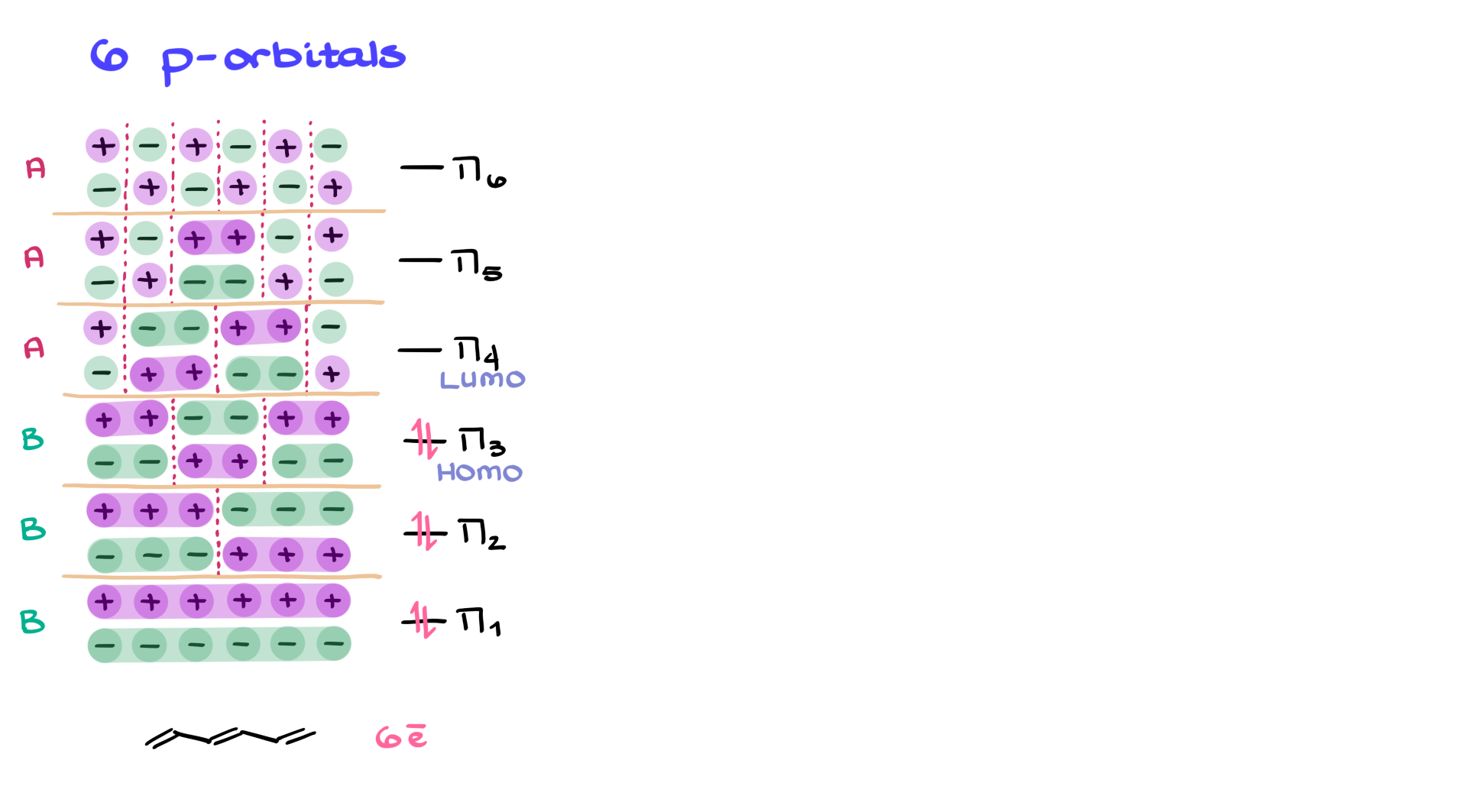

When drawing these orbitals, you might see shading, color, or symbols like pluses and minuses. Those don’t refer to charges—they represent the phases of the orbitals. It’s just a shorthand to track phase changes.

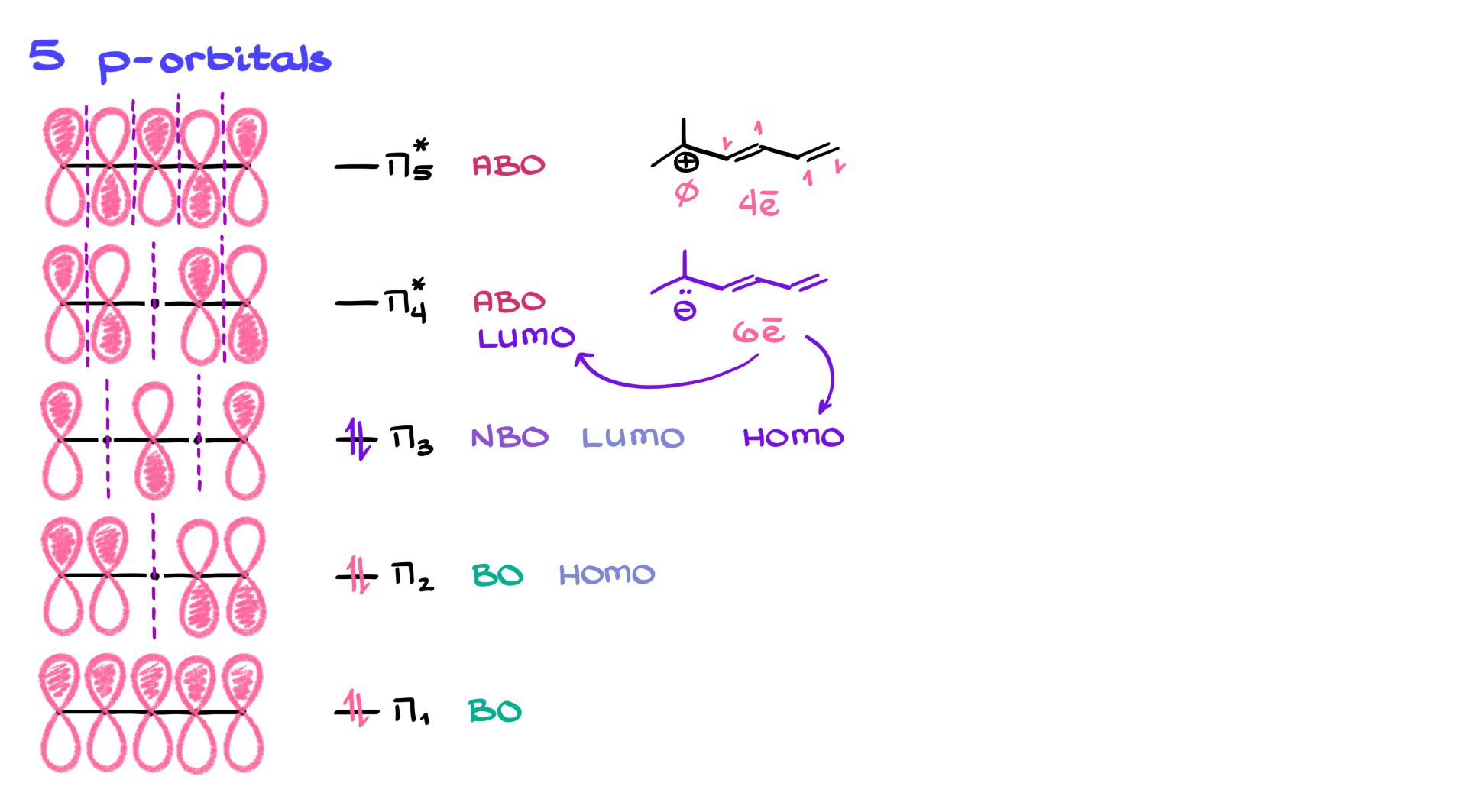

5 and 6 p-Orbital Systems

Looking at five-p orbital systems, like a cyclic carbocation, you’d have orbitals π₁ through π₅. Zero nodes at the bottom and four nodes at the top. Analyzing the interactions, you’d see bonding in π₁ and π₂, a non-bonding π₃, and anti-bonding orbitals at π₄ and π₅. For a molecule with four π electrons, like the carbocation, you’d fill π₁ and π₂—making π₂ the HOMO and π₃ the LUMO. If you switch to a carbanion version with six π electrons, you’d fill π₁, π₂, and π₃. So π₃ becomes the HOMO, and π₄ is now the LUMO.

Take it one step further to six-p orbital systems, like hexatriene. To save time, let’s skip drawing every orbital and use pluses and minuses to show phases. As you analyze the system, you’ll find that the lower three orbitals (π₁ to π₃) are bonding and the upper three (π₄ to π₆) are anti-bonding. With six π electrons, we’d fill up through π₃, making π₃ the HOMO and π₄ the LUMO.

Now, I know drawing all these orbitals can seem tedious at first, but it becomes second nature with practice. And it’s worth it because in chemistry—especially organic chemistry—the interactions that drive reactions often come down to HOMO and LUMO orbitals. Reactions like Diels-Alder, electrocyclic reactions like the Cope rearrangement, and many others hinge on the overlap of these orbitals.

Understanding how to draw, interpret, and assign HOMO and LUMO orbitals, and knowing their phases and how they align in space, will often be the key to predicting the right products and understanding reactivity and stereochemistry in these systems.