Mannich Reaction

In this tutorial, I want to talk about the Mannich reaction, which frankly looks like a total mess and yet somehow manages to give us a product. But let’s take it one step at a time.

When it comes to the Mannich reaction, we typically see a reaction between a ketone, an aldehyde, and an amine or ammonia. In most cases, the fact that we are reacting a ketone and an aldehyde is crucial because their difference in reactivity plays a key role. Although it is possible to come up with cases where that wouldn’t really matter, in general, we do need to consider it.

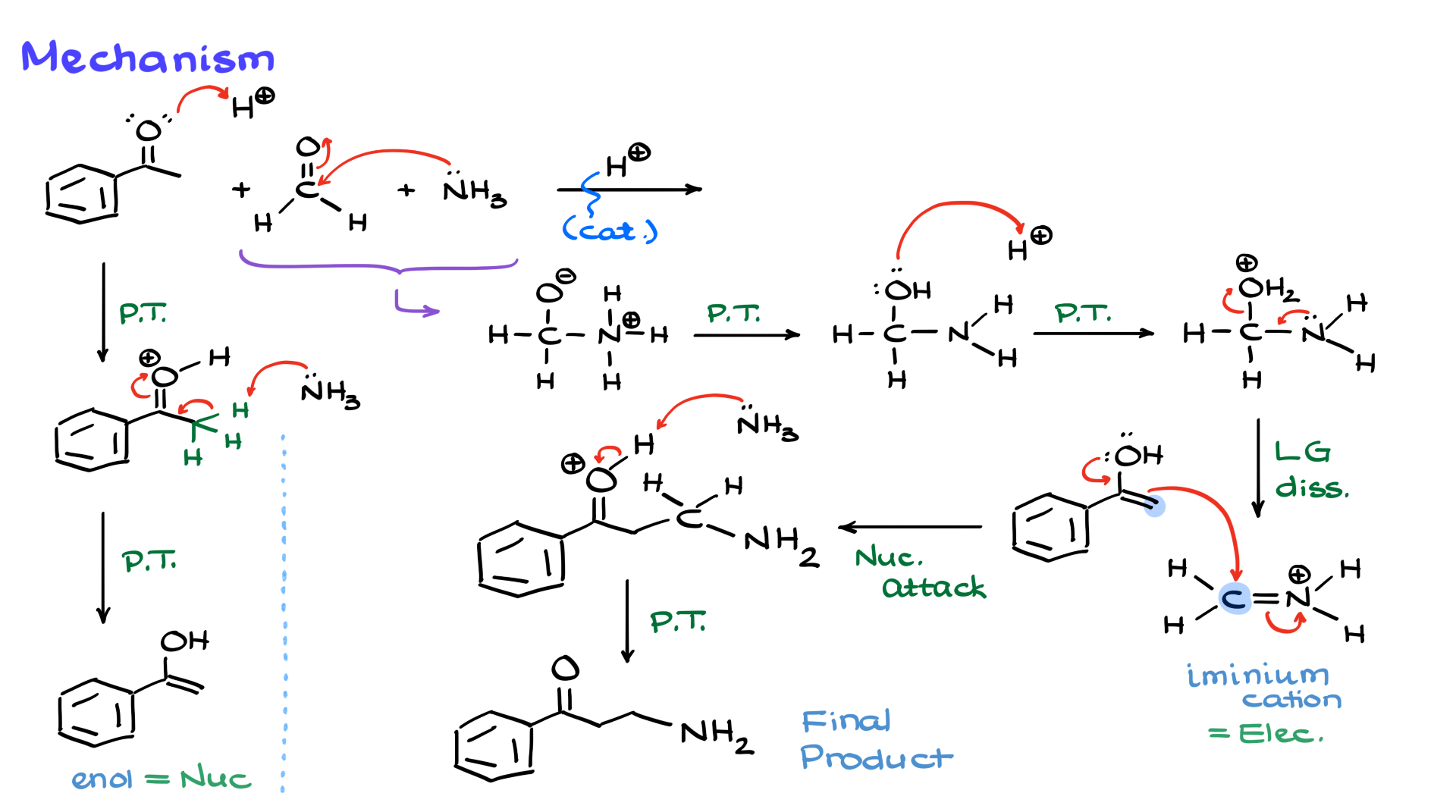

Mechanism of the Mannich Reaction

Let’s take a closer look at how this reaction works.

Since I am reacting ammonia, which is a nucleophile, with two different electrophiles, the difference in reactivity becomes important. Ammonia will react with the more electrophilic species, which in this case is formaldehyde, because aldehydes are generally more reactive toward nucleophiles. As a result of this nucleophilic attack, we get an intermediate, which, after a couple of proton transfers, gives us a neutral hemiaminal.

Since the reaction is carried out under slightly acidic conditions, I’ll introduce an acid—whatever that acid might be—and the next step will be the protonation of the hydroxyl group. I’ll show this OH grabbing a proton, forming water as a good leaving group, which then naturally dissociates. The nitrogen helps facilitate this dissociation, resulting in the formation of an iminium cation. At this point, the reaction essentially follows the steps of imine formation; however, I won’t take it all the way to the imine. I’ll leave it in the protonated form for now and set it aside while I turn my attention to the other component of the reaction mixture that I haven’t touched yet—the ketone.

Since we are working under acidic conditions, I’ll show the protonation of the carbonyl group, giving me a protonated carbonyl species. Now, I’m going to deprotonate this intermediate with ammonia, leading to the formation of the corresponding enol.

Now, here’s the fun part of the mechanism. On the left, I have an enol, and on the right, I have an iminium cation. The enol is a nucleophile, while the iminium cation is an electrophile. Naturally, these two will react with each other. This is a fairly standard nucleophilic attack, leading to the formation of a new carbon-carbon bond between the α-position of the carbonyl and the carbon of the iminium cation.

As a result of this attack, we get a charged intermediate, and the final step is to bring in another equivalent of ammonia to act as a base. This ammonia will deprotonate the intermediate, ultimately yielding the final product. In this case, I’ve created two new bonds—one between the carbons and another between the carbon and the nitrogen. If I color-code the pieces of my final product, the purple part comes from my ketone, the green carbon in the middle comes from formaldehyde, and the nitrogen part comes from ammonia. It takes a little imagination to see how all these pieces come together, so let’s look at a few examples to reinforce this concept.

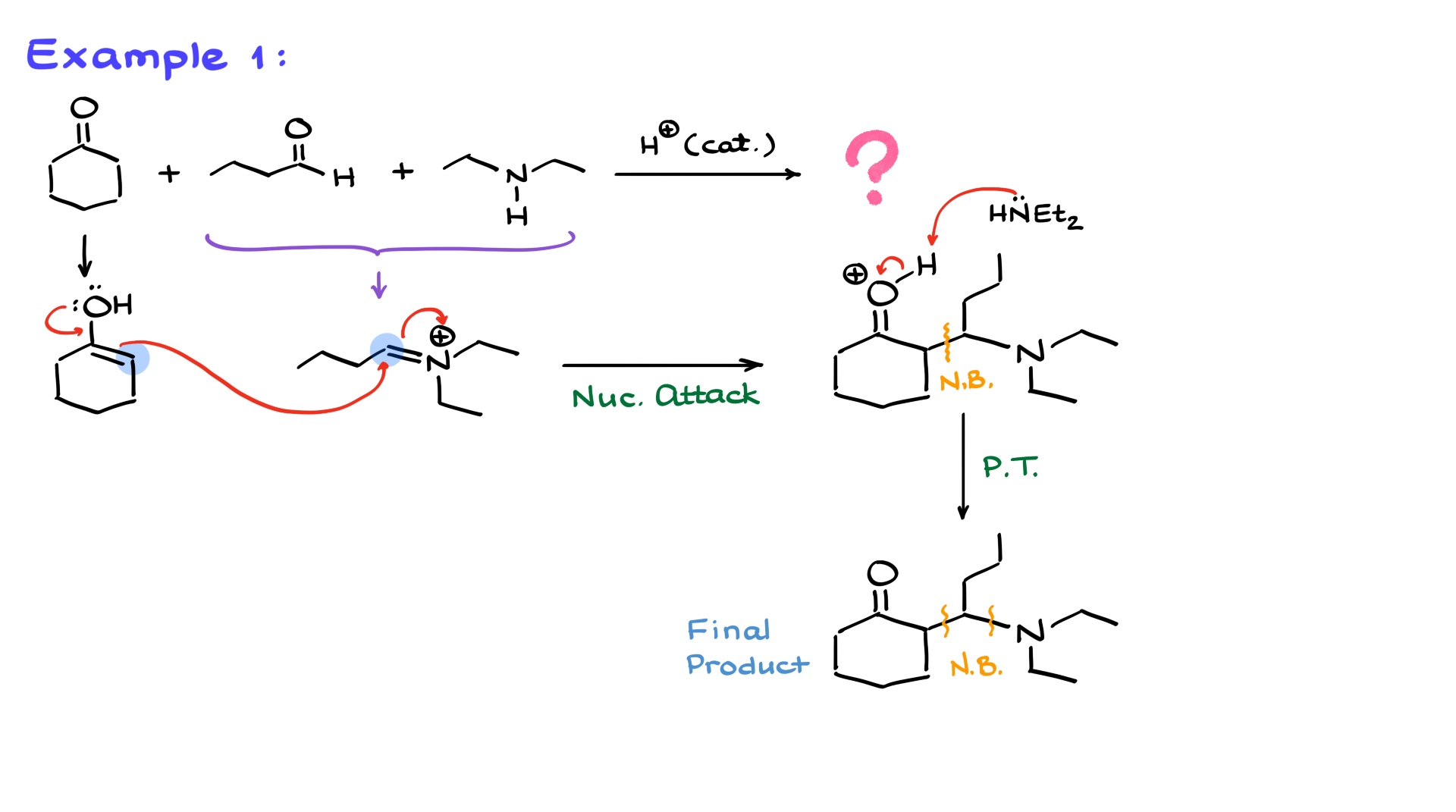

Mannich Reaction Example 1

In my first example, I have cyclohexanone as my ketone, butanal as my aldehyde, and diethylamine playing the role of the amine in this reaction.

Since the aldehyde is more electrophilic, my amine first reacts with it, giving me an iminium intermediate. Then, I analyze my ketone, leading to the formation of the enol, which serves as my nucleophile.

Now comes the best part of the mechanism—the nucleophilic attack. We’re going to have the nucleophile (enol) attack our electrophile (iminium ion). This results in the formation of a new carbon-carbon bond between the α-position of the enol and the carbon of the iminium intermediate. I’ll highlight this newly formed bond in the structure. Additionally, the carbon-nitrogen bond originated from the first step when the iminium intermediate was formed.

At this stage, all that remains is to deprotonate the molecule. I’ll show another equivalent of diethylamine coming in, pulling off the proton, and giving us our final product. Once again, I’ve created two new bonds—one carbon-carbon bond and one carbon-nitrogen bond. So, from three seemingly simple molecules, we’ve built a fairly complex structure in what is considered a one-step reaction. Well, not one step mechanistically, but one step synthetically.

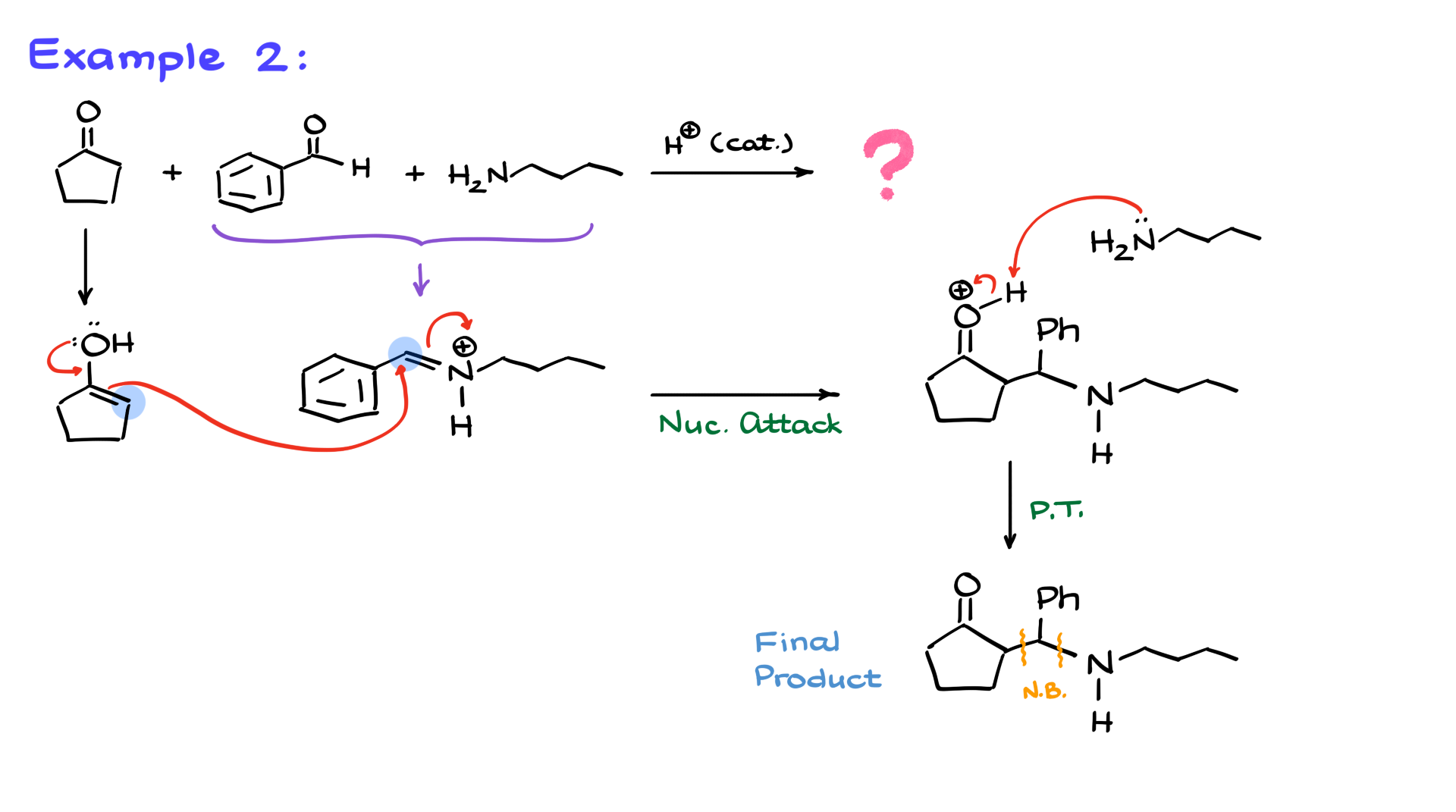

Mannich Reaction Example 2

Alright, ready for another example? Let’s check out this mixture over here.

I have cyclopentanone as my ketone, benzaldehyde as my aldehyde, and butylamine as my amine. Just like before, the first step is the reaction between the aldehyde and amine, yielding an iminium intermediate. Then, I’ll show how cyclopentanone is converted into the corresponding enol.

Now, I’ll show the reaction between these two species. The nucleophile, my enol, attacks the iminium ion, which is an electrophile, forming a new carbon-carbon bond between the α-position of the enol and the carbon of the iminium ion. This gives us the following structure.

As in the previous example, the next step involves a proton transfer. We need to deprotonate the molecule, so I’ll show butylamine coming in, pulling off the proton, and giving us the final product. Once again, the new bonds created in this reaction are the carbon-carbon bond and the carbon-nitrogen bond, which I’ll highlight in the structure.

As you can see, the Mannich reaction is an excellent method for synthesizing β-aminocarbonyl compounds, which can be extremely useful for targeted synthesis, particularly in the creation of natural products and potentially biologically active compounds or drugs. However, like any multi-component reaction, the Mannich reaction does come with some challenges. The biggest issue is the formation of side products. The reaction is highly sensitive to the precise procedure used and, to some extent, the skill of the chemist performing it. But with some practice, this reaction can give decent yields, and once you’ve worked through it a few times on paper, predicting the products becomes much easier.