Hydrohalogenation of Alkenes

This tutorial is all about the hydrohalogenation of alkenes—breaking down the reaction mechanism, Markovnikov’s rule, and those pesky carbocation rearrangements that always seem to complicate things. So, grab a cup of coffee, pull out your notebook, and let’s dive in.

What is Hydrohalogenation?

Hydrohalogenation is a reaction where an alkene reacts with a hydrogen halide (HX), where X is typically chlorine, bromine, or iodine. During this reaction, one carbon of the alkene receives a hydrogen, while the other carbon gets the halide.

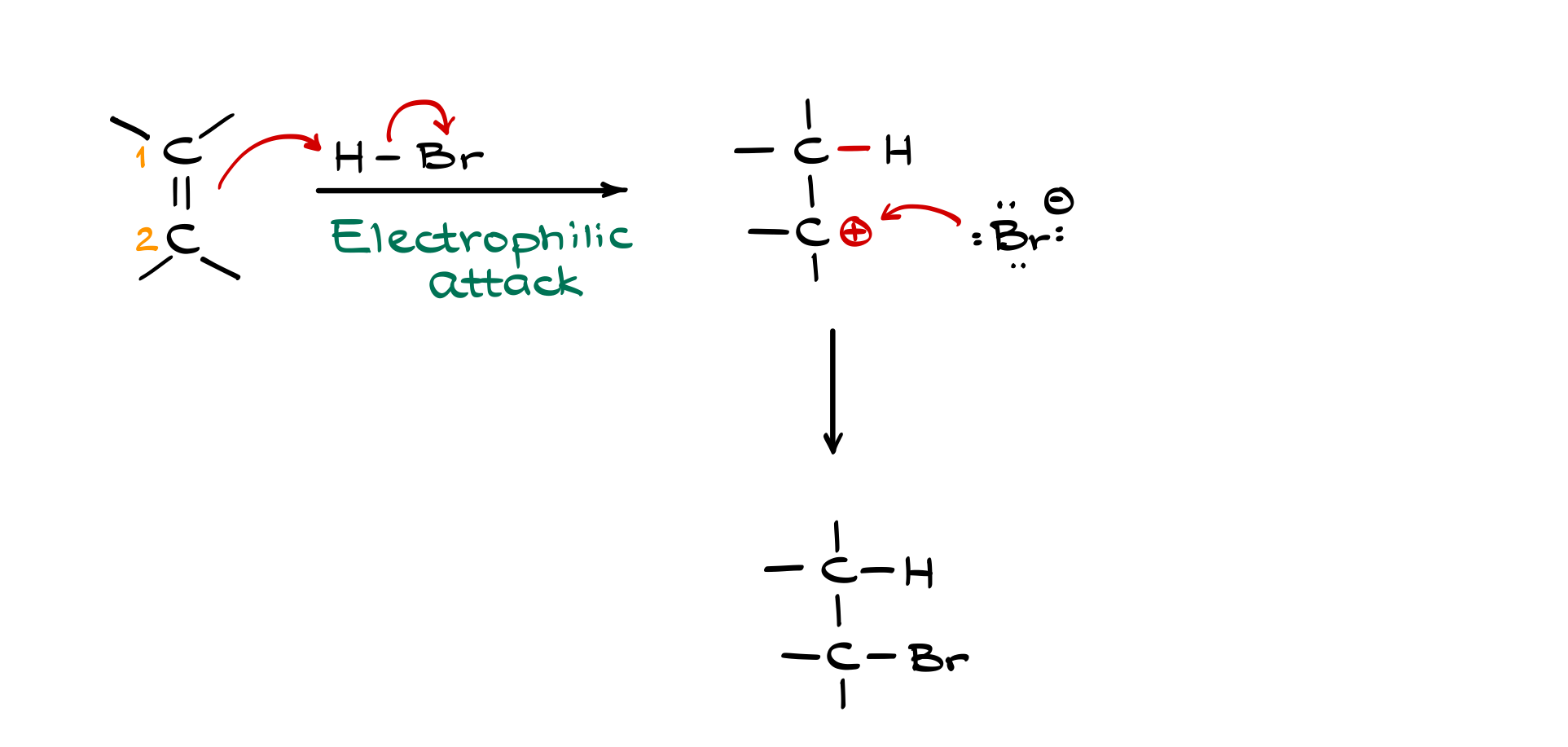

The Mechanism of Hydrohalogenation of Alkenes

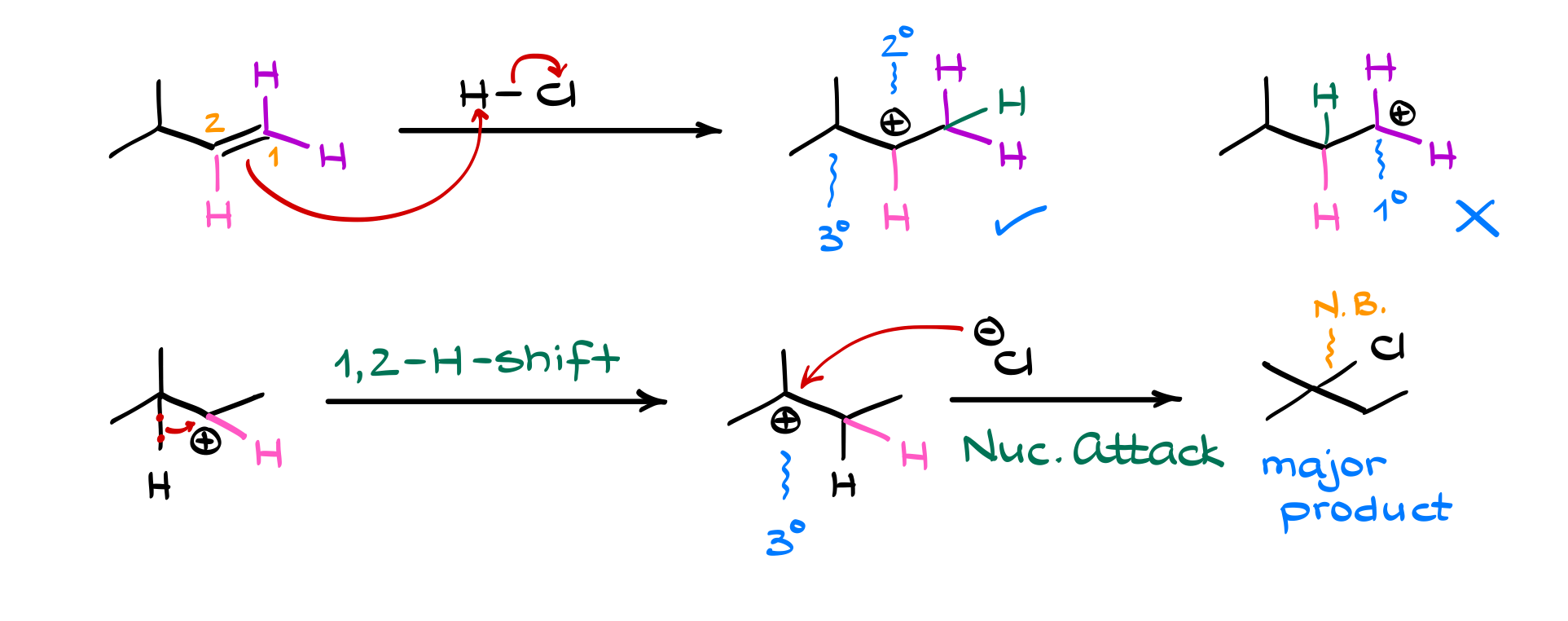

To understand this, let’s consider a generic alkene with two carbons, labeled carbon 1 and carbon 2. The double bond in the alkene acts as a nucleophile, meaning its electrons are attracted to the positively charged hydrogen in the HX molecule. The hydrogen-halide bond in HX is highly polarized—bromine, for example, is very electronegative, pulling electron density away from the hydrogen, making it highly electrophilic.

Since we have a nucleophile (the alkene) and an electrophile (HX), they react. This first step is called the electrophilic attack because the alkene’s electrons attack the hydrogen. When the alkene donates electrons to form a new bond with the hydrogen, the pi bond breaks, leaving the other carbon electron-deficient—creating a carbocation. Meanwhile, the halide (X⁻) is now free in solution as a negatively charged ion.

At this stage, we have a highly reactive carbocation, which is electrophilic because it is electron-deficient. The negatively charged halide (Br⁻, Cl⁻, etc.) then acts as a nucleophile and attacks the carbocation, forming a new bond. This step is called the nucleophilic attack, and it gives us our final product: a molecule where the hydrogen is attached to one carbon and the halide is attached to the other.

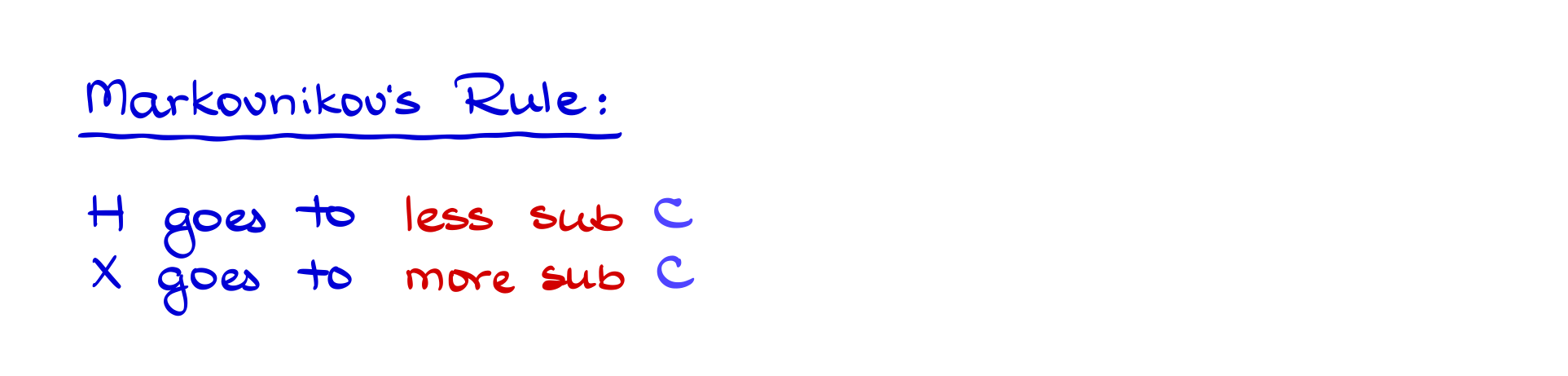

Markovnikov’s Rule

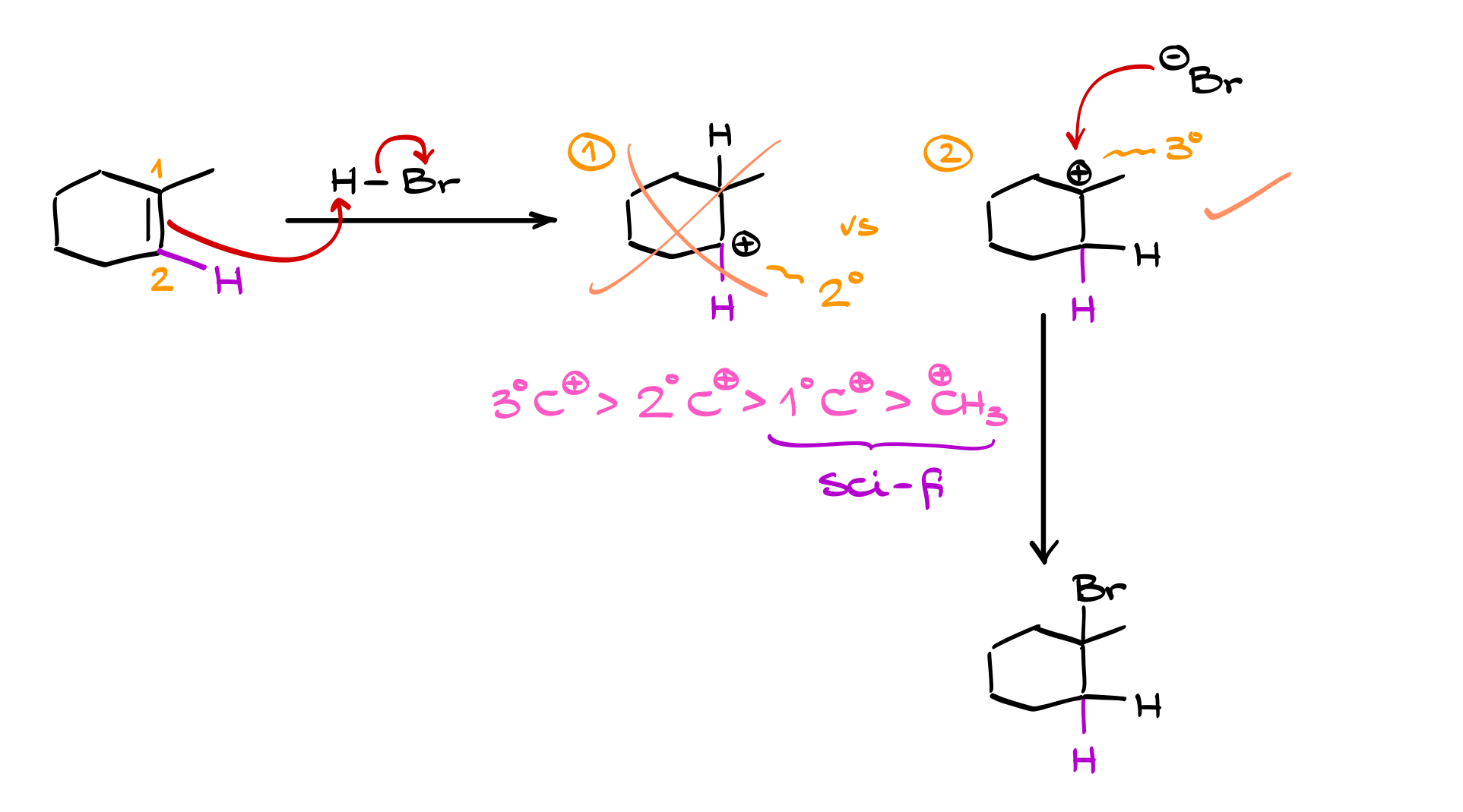

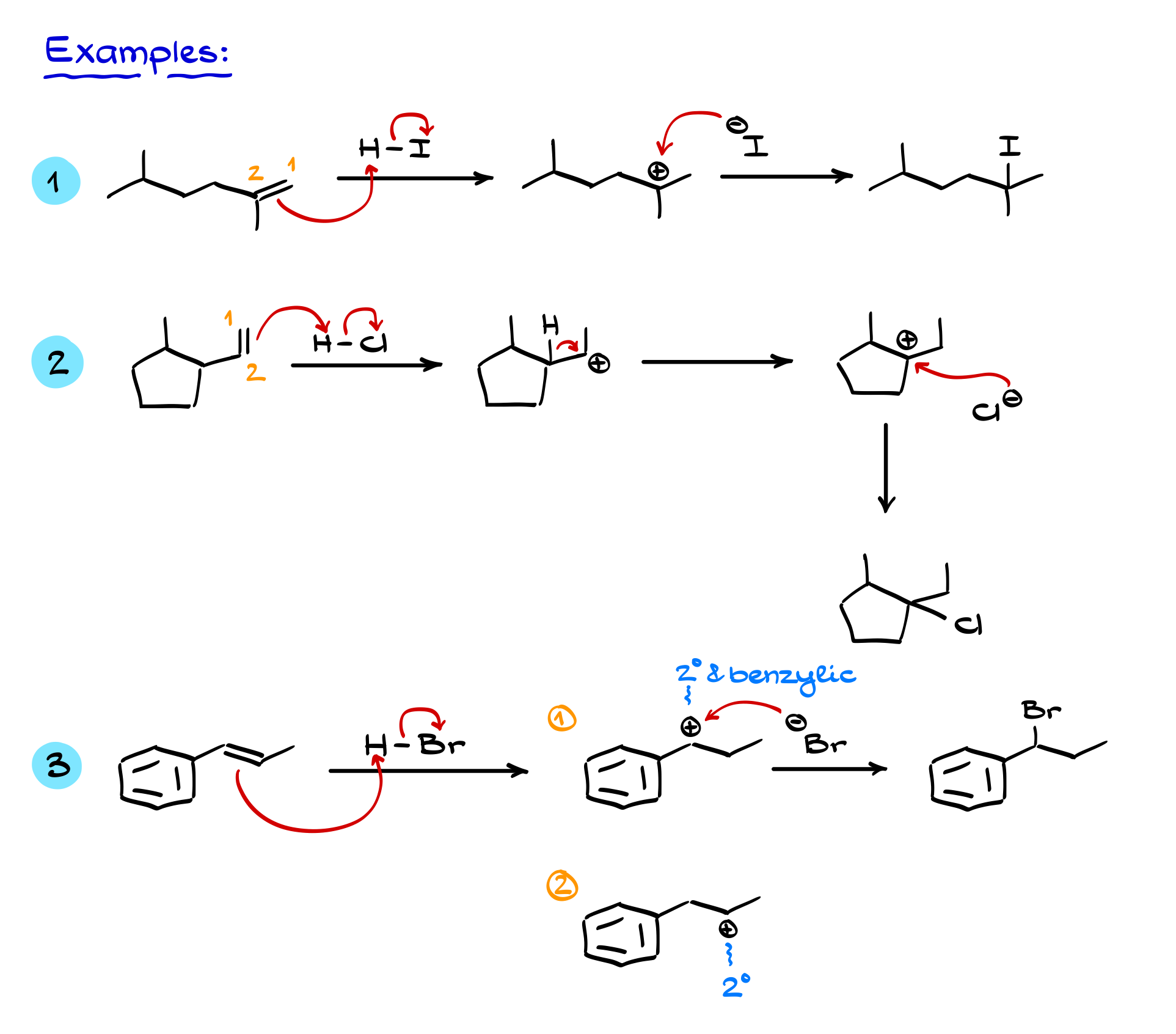

Let’s apply this to a real molecule—1-methylcyclohexene. Here, we again label our carbons as carbon 1 and carbon 2. The double bond serves as a nucleophile, attacking the hydrogen from HBr, while the electrons from the HBr bond return to bromine, forming Br⁻.

Now, we have a choice. Either carbon 1 or carbon 2 can receive the hydrogen. If carbon 1 gets the hydrogen, a carbocation forms on carbon 2, and if carbon 2 gets the hydrogen, the carbocation forms on carbon 1. The key here is carbocation stability:

• A tertiary carbocation (three carbon attachments) is more stable than a secondary carbocation (two carbon attachments), which is more stable than a primary carbocation (one carbon attachment).

• A methyl (CH₃⁺) carbocation is extremely unstable and practically non-existent in nature.

Since a tertiary carbocation is more stable than a secondary carbocation, the reaction favors the pathway that produces the more stable intermediate. This observation was formulated by Vladimir Markovnikov in the 19th century, known as Markovnikov’s rule. The rule states that in hydrohalogenation reactions, the hydrogen adds to the less substituted carbon (the one with fewer carbon attachments), while the halide attaches to the more substituted carbon (the one with more carbon attachments). This ensures the formation of the most stable carbocation.

Interestingly, Markovnikov originally noticed cases where the halide sometimes ended up on unexpected positions in the molecule. He had no idea why—because at the time, carbocations hadn’t been discovered! Today, we know that carbocation rearrangements are responsible for these unexpected results.

Carbocation Rearrangements

Let’s consider an example where rearrangement occurs. In a typical reaction, the first step is still the electrophilic attack, where the double bond donates electrons to the hydrogen, forming a carbocation. If the initial carbocation isn’t as stable as a nearby alternative, a rearrangement can occur.

For example, if we form a secondary carbocation adjacent to a tertiary carbon, the system can stabilize by shifting a nearby hydrogen (along with its bonding electrons) to the carbocation site. This is called a 1,2-hydride shift, and it results in the formation of a more stable tertiary carbocation. Once the carbocation has stabilized, the halide (X⁻) can attack, forming the final product.

If you didn’t account for the rearrangement, you’d expect a different product! But because carbocations always seek out the most stable configuration, the major product follows this rearranged pathway.

More Examples and Special Cases

In some cases, we have to decide between multiple possible carbocations. If one of them is benzylic—meaning it is adjacent to a benzene ring—it will be resonance stabilized, making it much more favorable than a typical secondary or tertiary carbocation. These resonance effects can often override even Markovnikov’s rule in determining the final product.

By considering these rules—Markovnikov’s rule, carbocation stability, and possible rearrangements—we can accurately predict the outcome of hydrohalogenation reactions.

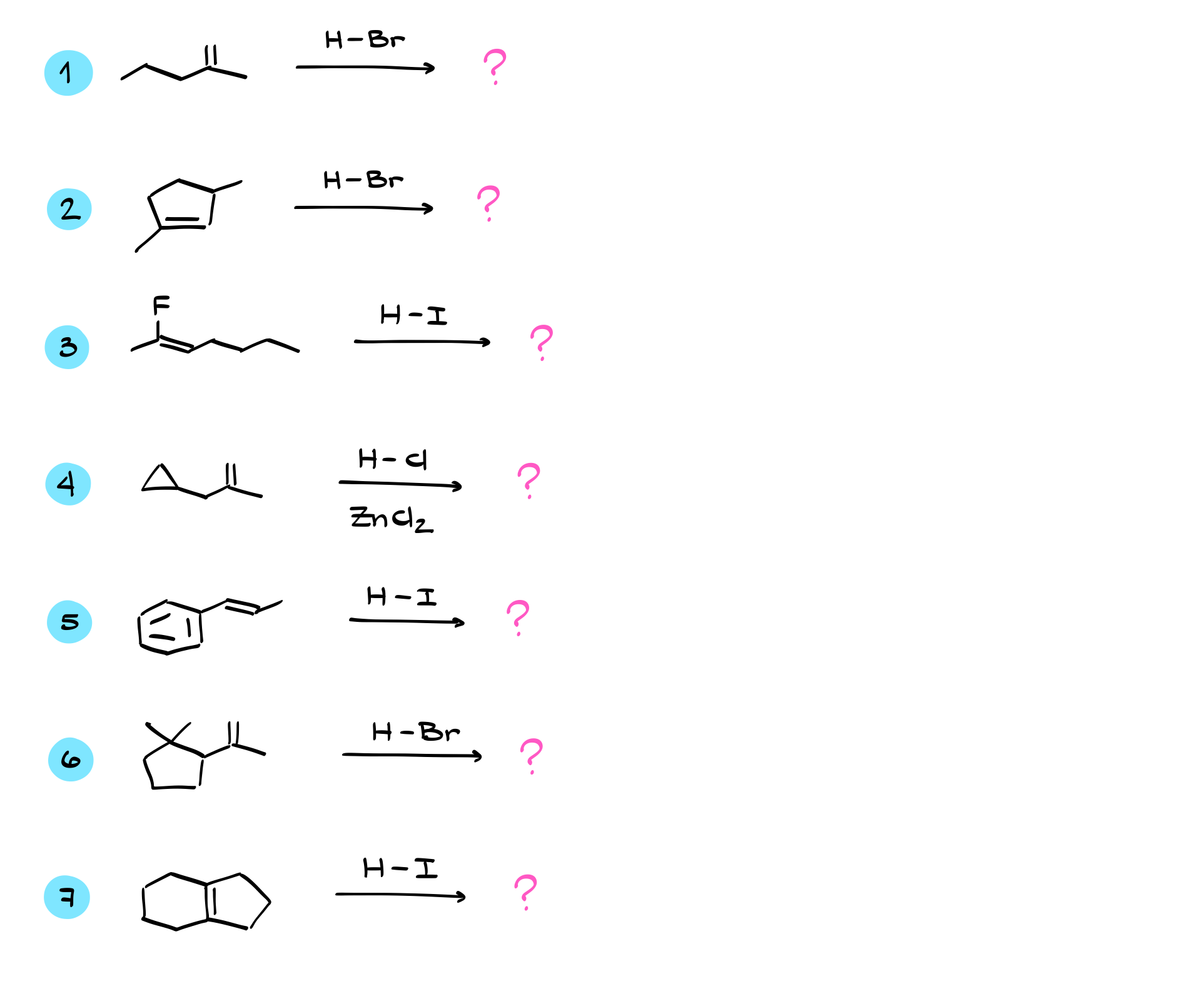

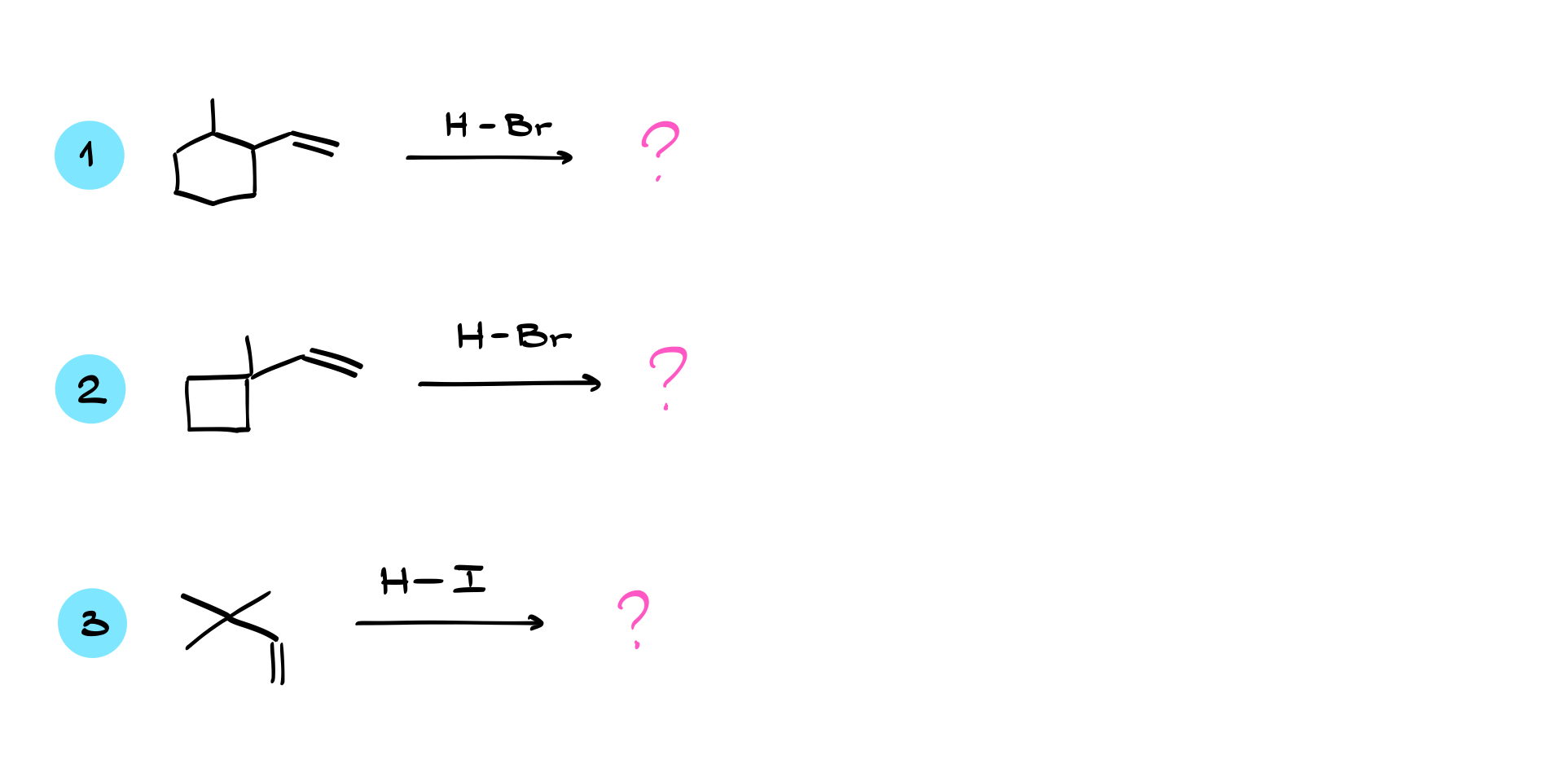

Practice Questions

Would you like to see the answers and check your work? Become a member today or login if you’re already a member and unlock all members-only content!