Halogenation of Alkenes

In this tutorial, I want to talk about the halogenation of alkenes, which is a signature reaction of alkenes that has all the components of a potential perfect disaster. This reaction has a rather complicated mechanism, and it is also stereospecific, so the stereochemistry is always something to be very careful with. In this tutorial, we are going to cover everything you need to know about this reaction. Grab a cup of coffee, a notebook, and a pen, and let’s get started.

Halogenation is a type of reaction where we add some sort of halide—like chlorine, bromine, iodine, or even an interhalide (where those are mixed)—across the double bond of an alkene. Each carbon of what used to be the alkene will get one of those halogens. The important thing here, as I mentioned a moment ago, is that the reaction is stereospecific, and in this particular case, it is an anti-addition. That means both halogens will end up on opposite sides of the molecule—or rather, on opposite faces of the molecule, facing in different directions.

Mechanism of the Alkene Halogenation

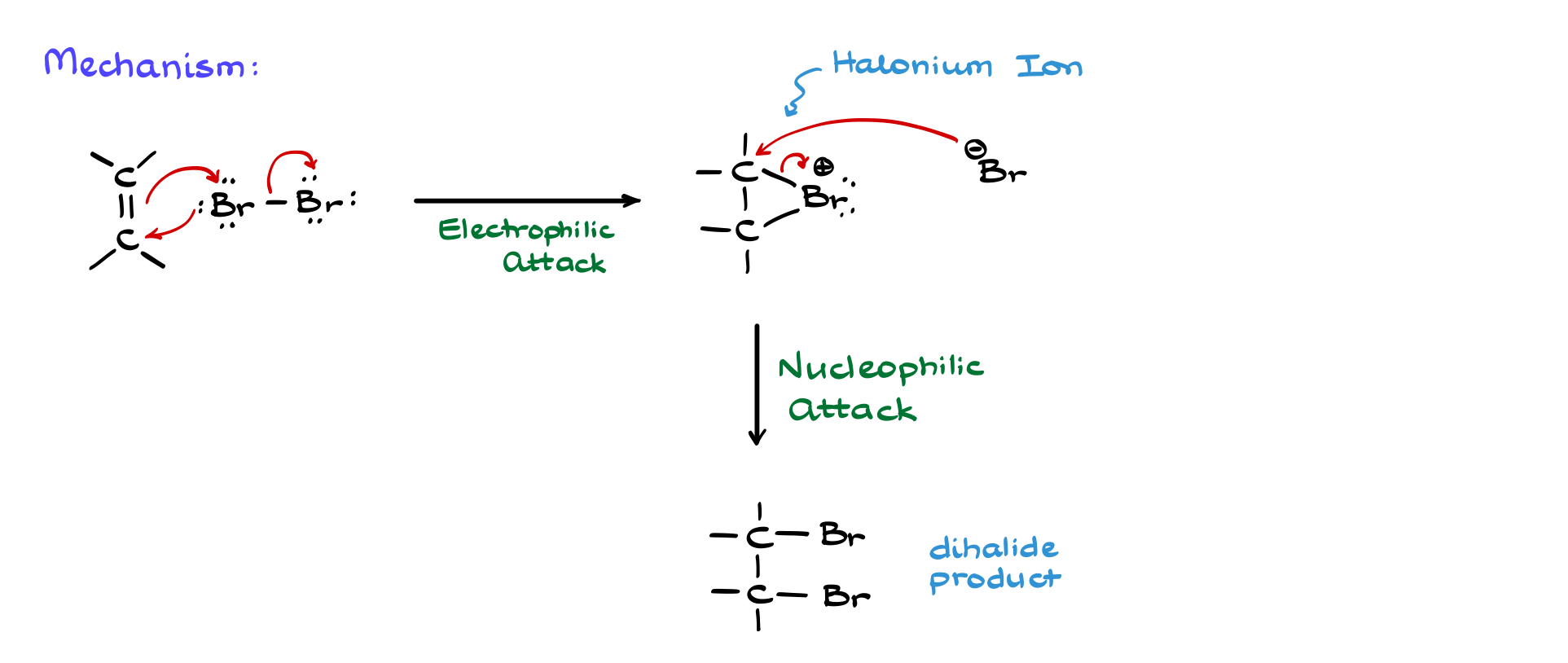

Now, when it comes to the mechanism of this reaction, it is probably one of the weirdest ones you have seen in your class so far. Let’s start with a generic alkene and a bromine molecule reacting with each other. In this case, bromine is our electrophile—in other words, the molecule that is electron-loving, pulling electron density toward itself. The double bond of the alkene acts as the nucleophile, providing the electron density to make new bonds in this reaction.

Here’s where things get interesting. When this reaction begins, we expect the normal flow of electron density from the nucleophile to the electrophile. The pi bond donates electrons to bromine, breaking the Br-Br bond and shifting electrons toward the other bromine. Everything seems perfectly normal at first. However, at the same time, the original bromine atom receiving the electron density attacks the alkene back, forming another bond. As a result of this transformation and electron flow, we get the following intermediate: a three-membered ring with the bromine now bonded to both carbons simultaneously, along with a Br⁻ ion.

I know it feels a little weird to see a halogen like bromine carrying a positive charge, but that’s how this mechanism works, so we are going to roll with it. The key here is to recognize where all the electrons are, so let’s analyze this carefully. The electrons of the double bond now form a bond between one of the carbons and the bromine. The electrons that were originally between the two bromine atoms now reside on Br⁻. Finally, the electrons from the bromine that attacked the double bond are now part of the bond connecting bromine to the other carbon.

This three-membered intermediate is commonly referred to as a halonium ion—specifically, a bromonium ion in this case. The next step in the mechanism is the nucleophilic attack, where Br⁻ attacks one of the carbons, forming a new C-Br bond. Let’s say Br⁻ attacks the top carbon. This causes the electrons to shift back to the Br⁺, giving us the final product, where each carbon is connected to its own bromine atom.

As long as we are dealing with simple halogenations like this, the reaction always proceeds in two steps: an initial electrophilic attack followed by a nucleophilic attack. Looks easy enough, right? Well, not so fast.

Example

Let’s look at an actual example.

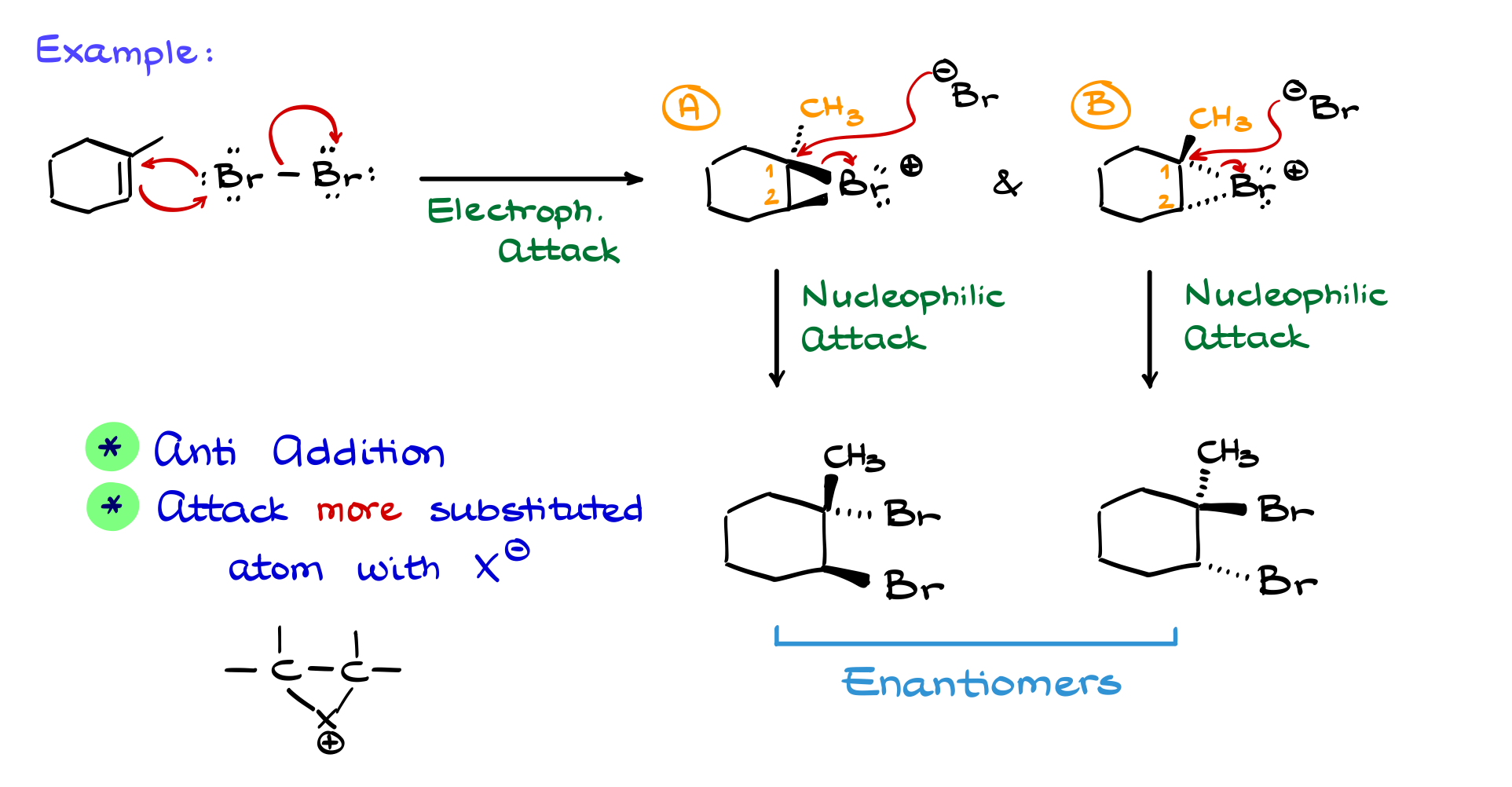

Suppose we react 1-methylcyclohexene with a bromine molecule. In step one, during the electrophilic attack, the double bond donates electrons to bromine, breaking the Br-Br bond. The initial bromine atom then back-attacks one of the carbons, forming the second C-Br bond.

Since this attack can happen from either the front or back face of the molecule, we end up with two different intermediates. In the first case, let’s call it intermediate A, bromine attacks from the front face, forcing the methyl group (CH₃) to point away. In the second case, intermediate B, bromine attacks from the opposite side, forcing the methyl group to face toward us.

Now comes the nucleophilic attack. Br⁻ attacks to open the halonium ion, predominantly attacking the more substituted carbon. Here, we label the carbon atoms as 1 and 2. Carbon 1 has more groups attached than carbon 2, making it more substituted. Br⁻ therefore attacks carbon 1, breaking the bond to Br⁺ and forming the final product.

The key thing to notice here is that carbon 1 undergoes stereochemical inversion. Since bromine must attack from the opposite side of Br⁺, it pushes everything around, flipping carbon 1. This means the methyl group that was originally pointing away now faces toward us, while Br⁻ ends up on the opposite side. The original bromine on carbon 2, however, remains in place since we did not touch that bond.

A similar situation occurs with intermediate B. Again, Br⁻ attacks the more substituted carbon (carbon 1), breaking the bond to Br⁺ and producing a final product where the two bromine atoms are on opposite faces of the molecule. The relationship between these two molecules is that of enantiomers—non-superimposable mirror images. You can confirm this by assigning R and S stereodescriptors.

The most important takeaways from this reaction are:

- Halogenation follows anti-addition, meaning that the two halogens will always be on opposite faces of the molecule.

- The halonium ion always opens at the more substituted carbon because that is where the nucleophile attacks.

Why does this matter? Well, in simple halogenation reactions, it doesn’t make much of a difference. However, in reactions involving interhalogens (where different halogens are used) or alternative nucleophiles (something other than X⁻), this regioselectivity plays a crucial role.

Reaction with Interhalide

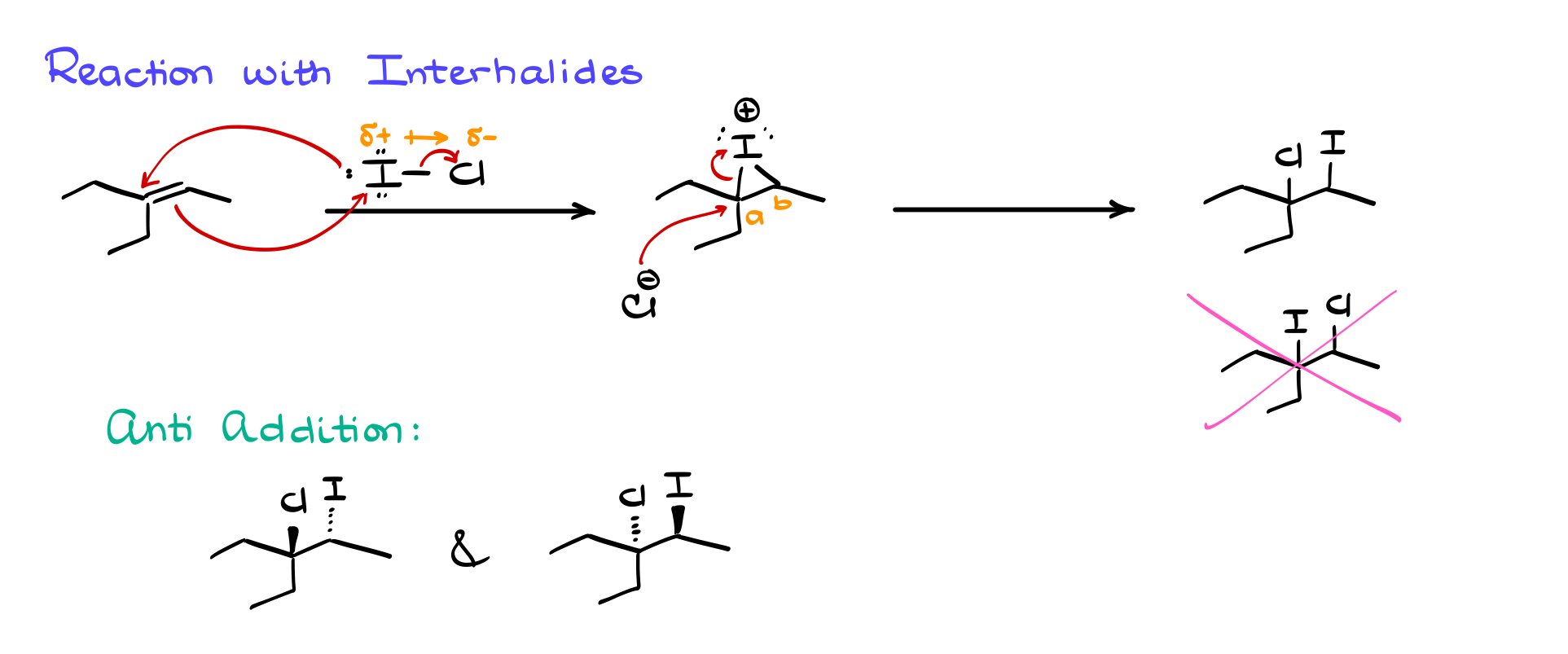

For example, let’s consider a reaction with iodine chloride (ICl).

The key question is: Which halogen is the electrophile, iodine or chlorine? Looking at the periodic table, we see that iodine is less electronegative than chlorine. This means chlorine pulls electron density away from iodine, making iodine more electrophilic.

Thus, in the first step, the double bond attacks iodine, breaking the I-Cl bond and forming an iodine-based halonium ion. The nucleophile, Cl⁻, then attacks the more substituted carbon, opening the ring and forming the final product. The regioselectivity is crucial here: the major product is the one where chlorine adds to the more substituted carbon, while the alternative product (where iodine is on the more substituted carbon) is not generally observed.

From a stereochemical perspective, the reaction remains an anti-addition. This means the iodine and chlorine will be on opposite faces of the molecule. One product will have chlorine facing toward us and iodine away, while the other product will have the reverse configuration. These two products are enantiomers.

Another Example

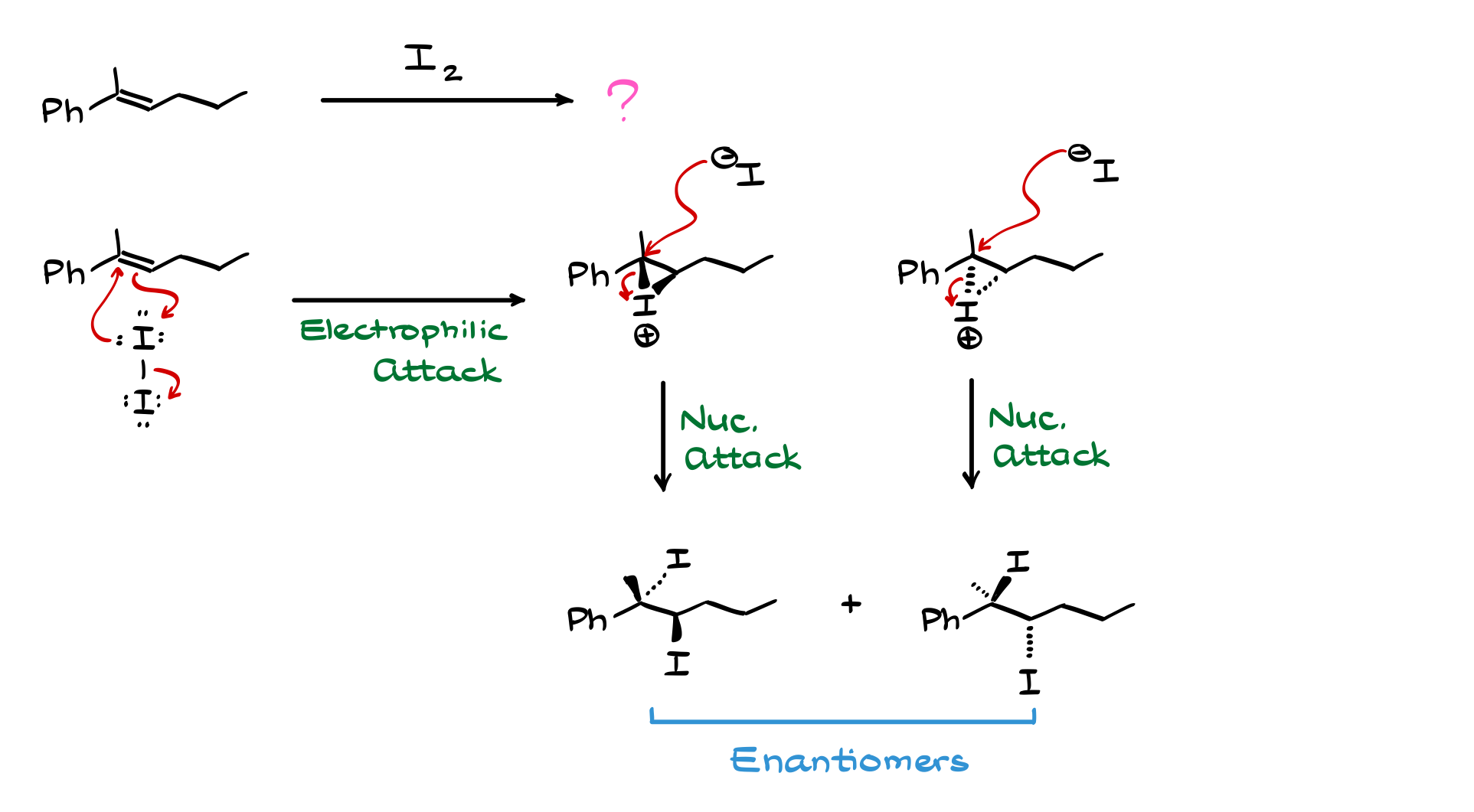

Here’s another example in which we’re going to react an alkene with iodine molecule.

Carefully following through the steps of the mechanism of this halogenation reaction we can see that we’re getting a pair of enantiomers.

Do We Always Get Enantiomers?

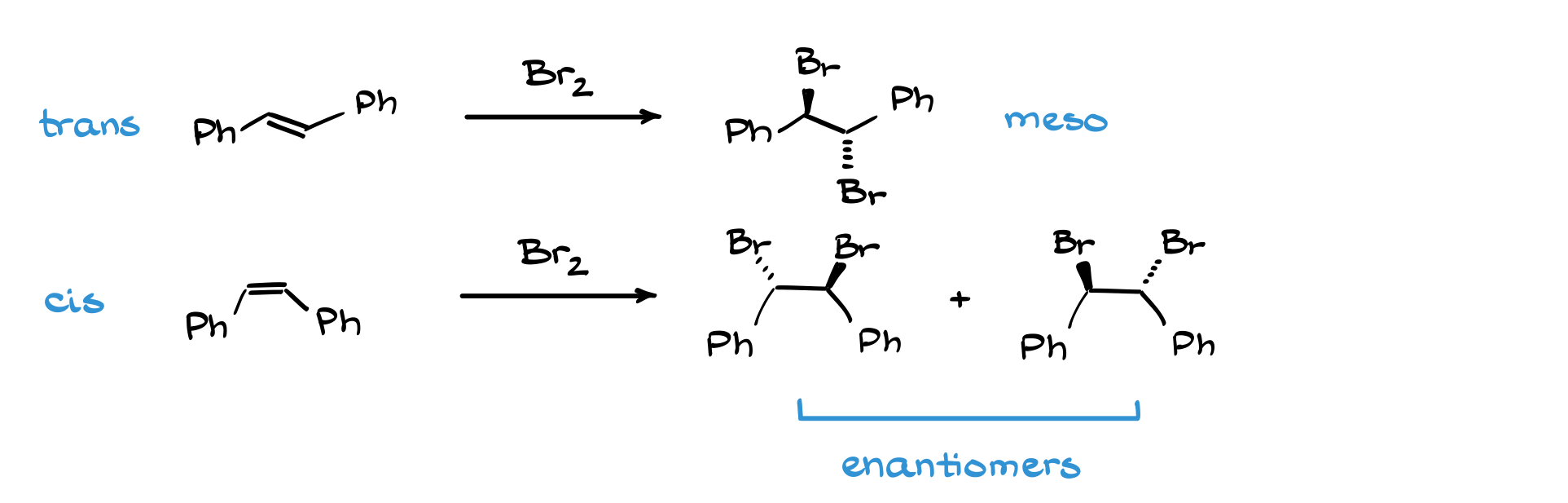

Does halogenation always produce enantiomers? Not necessarily. For instance, if you start with a meso compound or a molecule with existing stereocenters, you might end up with diastereomers instead. A good example is the bromination of cis- and trans-stilbene. Bromination of trans-stilbene gives a meso compound (achiral), while bromination of cis-stilbene gives enantiomeric products.

You can even generate diastereomers if your starting material already has chiral centers. For example, in a reaction where the starting material has a chiral methyl group, the bromination will create diastereomeric products.

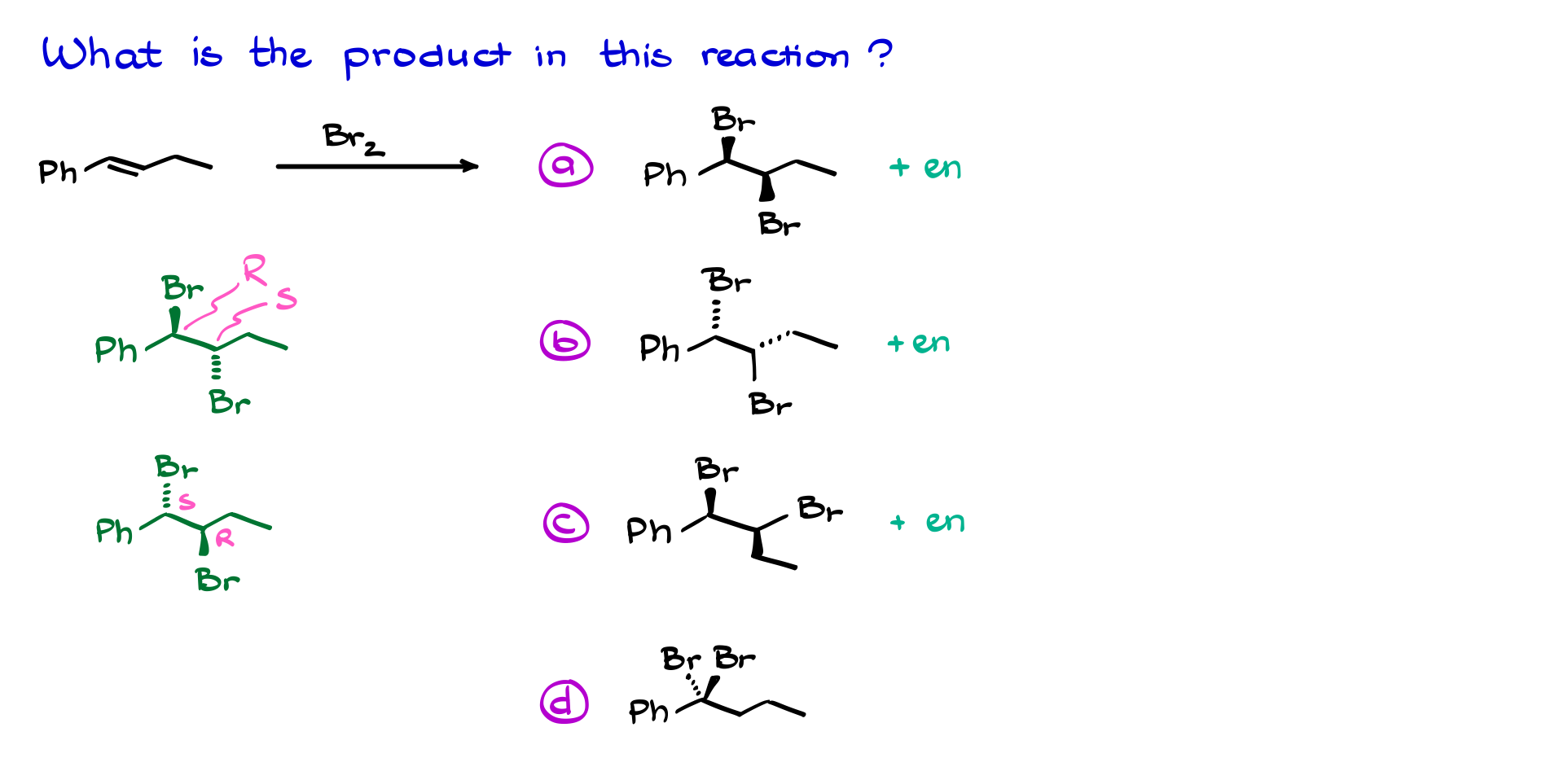

A classic trick used on exams is to test your ability to recognize stereochemistry. A seemingly straightforward multiple-choice question might ask for the correct product, but none of the options may look “correct” at first glance. This is because molecules don’t care how you draw them—they just exist in three-dimensional space. You must carefully analyze the molecular geometry and compare different conformations to determine the right answer.

So, as you can see, the halogenation of alkenes is full of tricky details, and you should always treat this reaction with the utmost respect. Otherwise, you might walk straight into the traps your instructor has set for the exam!

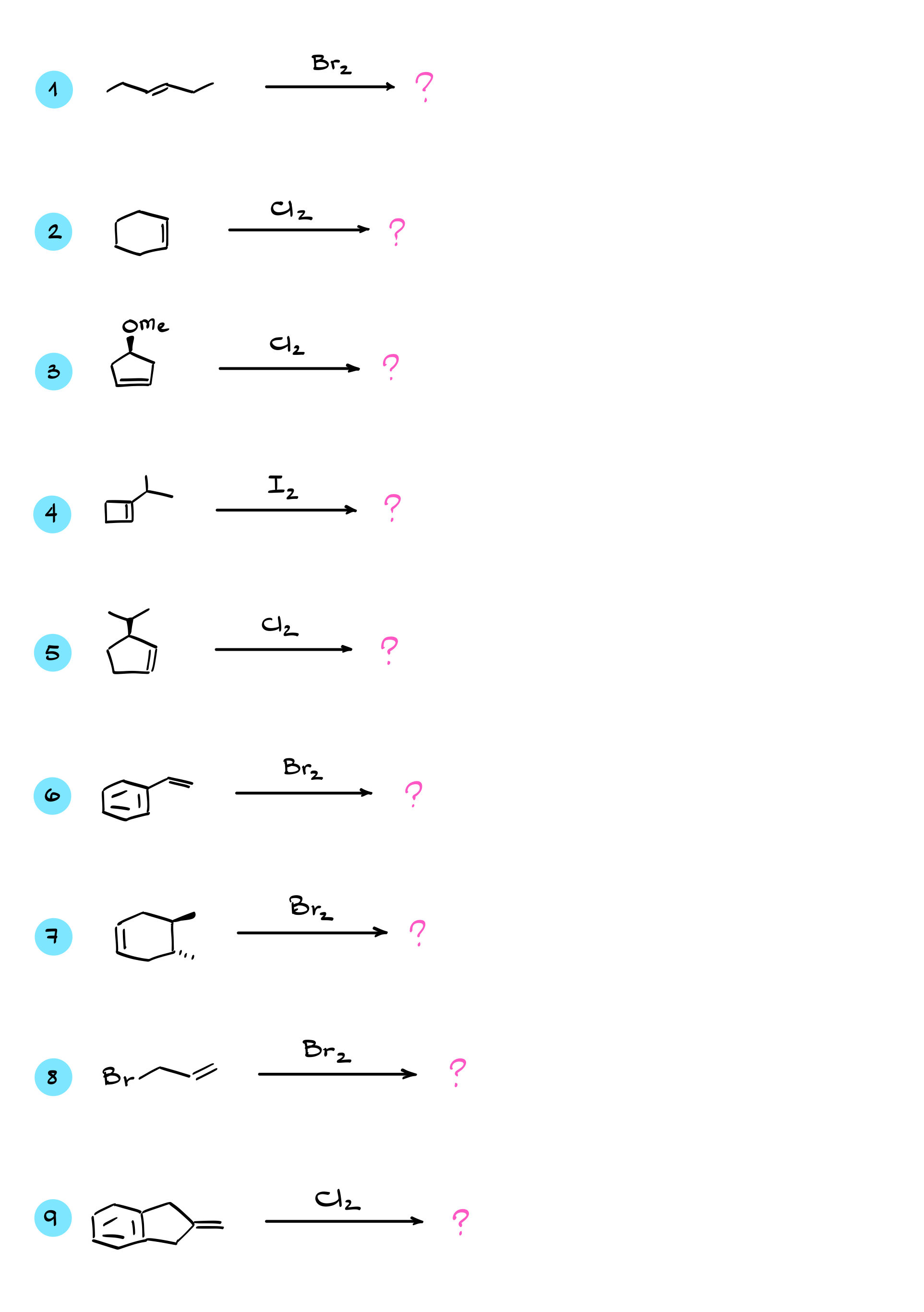

Practice Questions

Would you like to see the answers and check your work?

Sign up or login if you’re already a member and unlock all members-only content!