Gilman Reagent (Organocuprates)

In this tutorial, I want to talk about organocuprates, also known as Gilman reagents.

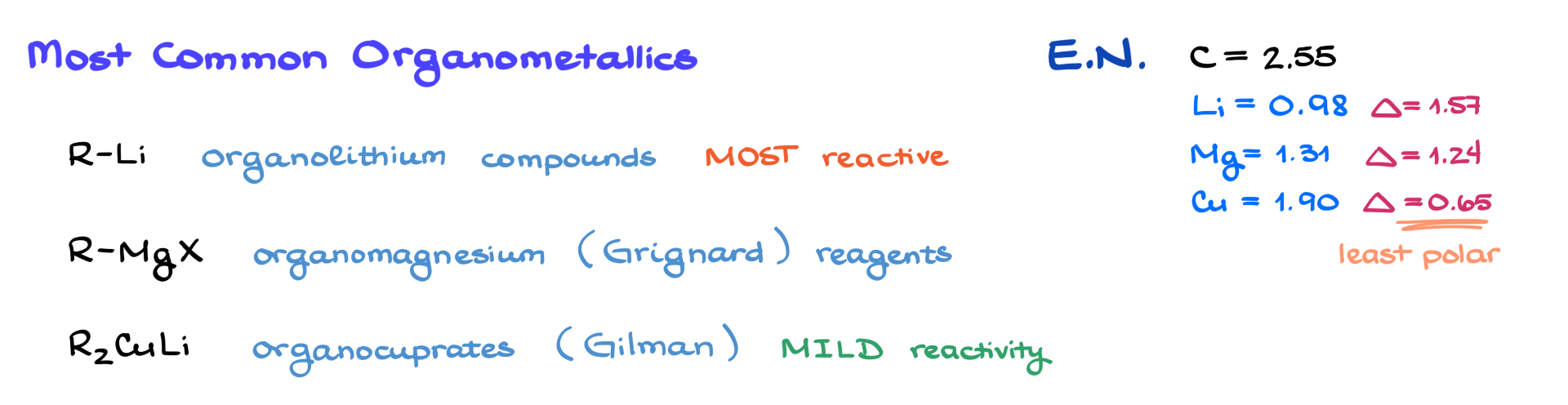

When it comes to organometallic compounds, we typically encounter three main types: organolithium compounds, organomagnesium compounds (commonly known as Grignard reagents), and organocuprates, or Gilman reagents. One of the key differences between these reagents is their reactivity.

Organolithium compounds are among the most reactive organometallic reagents, while organocuprates are much milder. This difference in reactivity is largely due to variations in electronegativity. Carbon has an electronegativity of about 2.55, while lithium’s electronegativity is 0.98. This creates a large difference of nearly 1.6, making the carbon-lithium bond almost ionic. As a result, carbon in organolithium compounds carries a nearly full negative charge, making it highly nucleophilic and extremely reactive.

In comparison, magnesium has an electronegativity of 1.31, so the electronegativity difference in Grignard reagents is about 1.2. This still results in a highly polar bond, but it is not as extreme as in organolithium compounds. When we move to copper, the electronegativity difference is much smaller. Copper itself is significantly more electronegative, and the difference between carbon and copper is only 0.65. This makes the carbon-copper bond almost nonpolar, meaning organocuprates are much less reactive than organolithium or Grignard reagents.

This drastic difference in bond polarity leads to a significant difference in reactivity. But before we discuss the specific reactions of organocuprates, let’s first look at how these compounds are made.

Preparation of Organocuprates (Gilman Reagents)

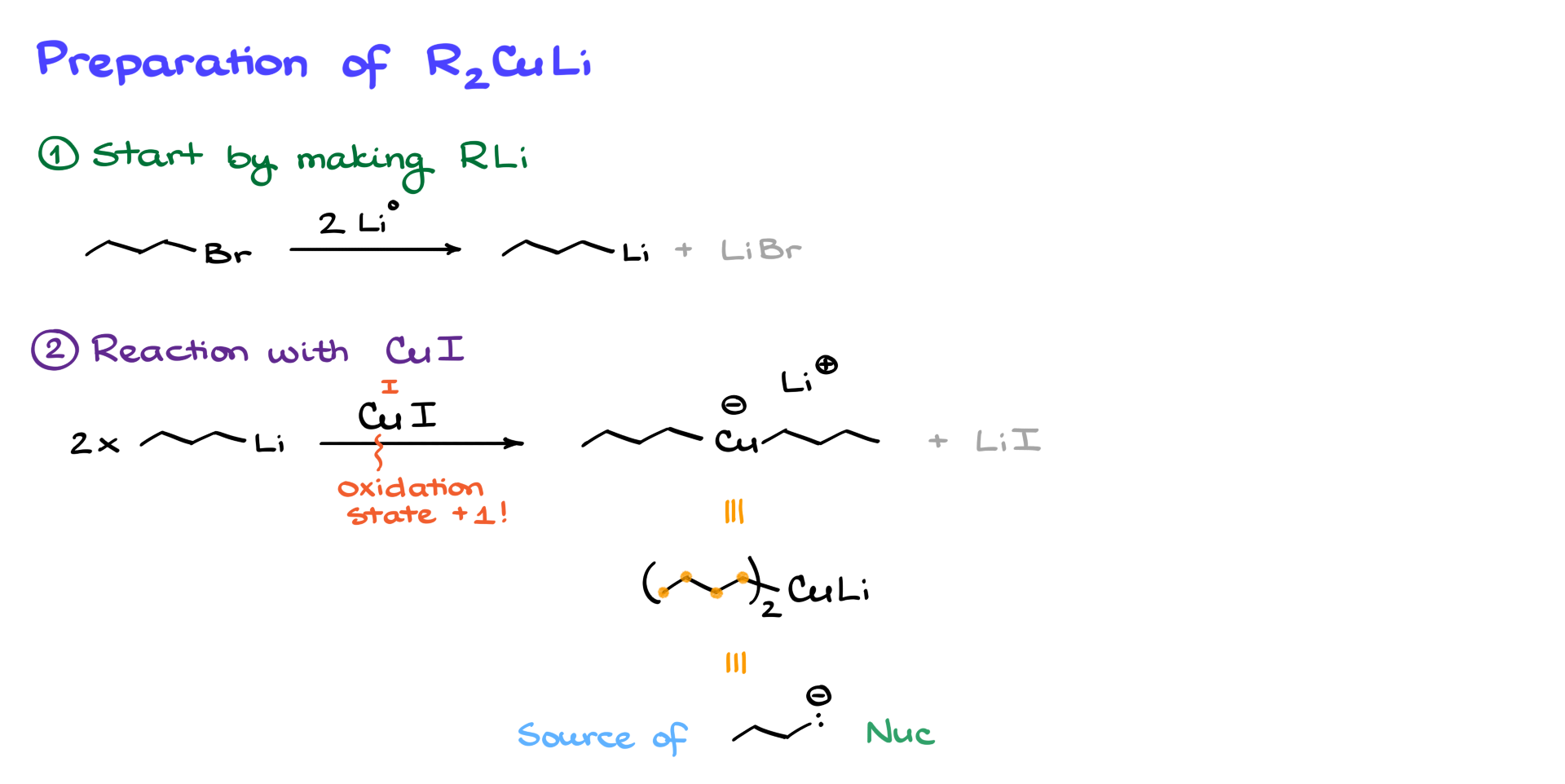

To prepare an organocuprate, we start by synthesizing an organolithium compound. For example, if we take butyl bromide and treat it with two equivalents of lithium, we obtain butyllithium along with lithium bromide as a byproduct (which we can ignore).

Next, to form the organocuprate, we react the organolithium compound with copper(I) iodide (CuI). It is important to use copper in the +1 oxidation state, as copper(II) does not work for this transformation. This reaction requires two equivalents of the organolithium compound and results in the formation of a lithium diorganocuprate (R₂CuLi).

This structure is often simplified in representations, with some instructors writing it as (R)₂CuLi or even just as R⁻ to indicate the nucleophilic nature of the alkyl group. However, be careful with these shorthand notations, as they can sometimes lead to confusion in carbon counting.

For the purposes of this tutorial, I will use the full representation of the organocuprate structure.

Reactions of Organocuprates

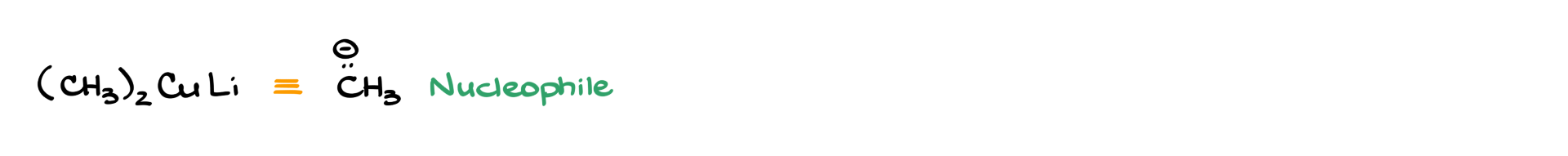

For the purposes of these mechanisms, I’m going to use the organocuprate throughout: lithium dimethylcuprate.

1. Reaction with Alkyl Halides

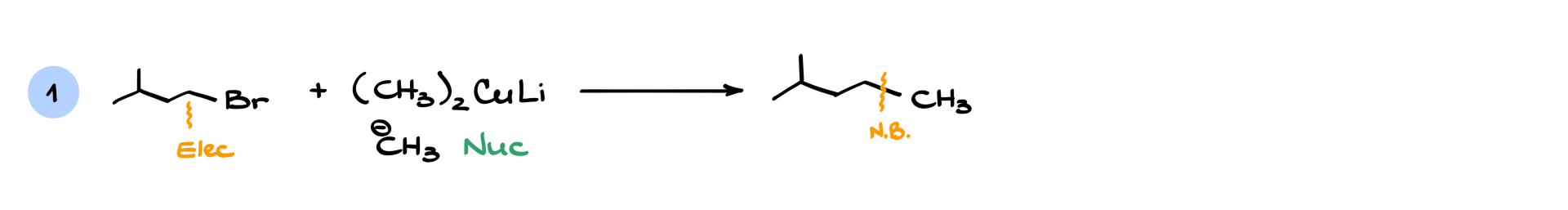

One of the key reactions of Gilman reagents is their ability to form new carbon-carbon bonds by reacting with alkyl halides.

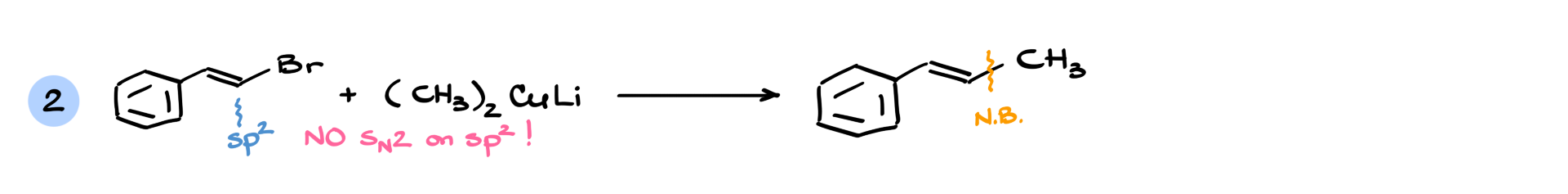

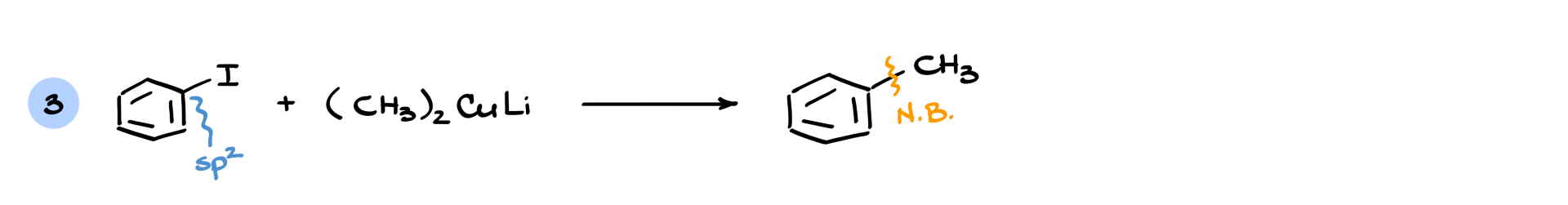

For example, if we take dimethylcuprate ((CH₃)₂CuLi) and react it with an alkyl bromide, the methyl group from the cuprate acts as a nucleophile, replacing the bromine and forming a new C–C bond. This may look like a simple SN2 reaction, but it is not.

To illustrate why this is not an SN2 mechanism, consider a case where the electrophilic carbon is sp² hybridized—normally, SN2 reactions do not occur at sp² carbons, yet this reaction still proceeds. Even more interestingly, if the electrophile is an aromatic ring, an SN2 reaction would be geometrically impossible, yet the reaction still works.

This shows that the mechanism is different from SN2 substitution, even though the result is the same: formation of a new carbon-carbon bond. In practice, this reaction can be somewhat messy, with variable yields depending on the substrate. However, when other coupling methods (such as palladium-catalyzed reactions) are unavailable, Gilman reagents can serve as a useful alternative.

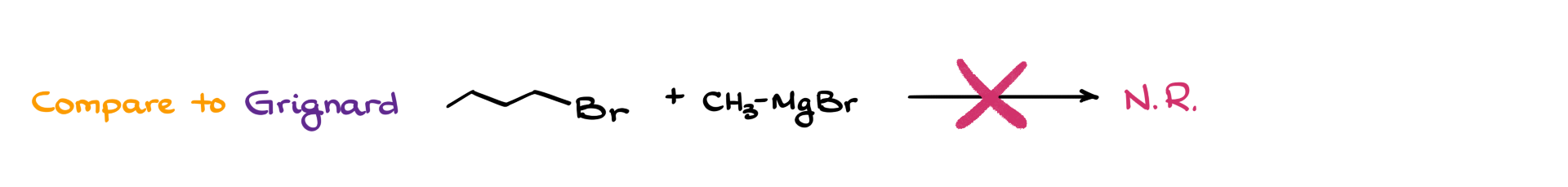

For comparison, if we try the same reaction with a Grignard reagent instead of a Gilman reagent, no meaningful reaction occurs at all. So while the organocuprate reaction may be imperfect, it is still better than no reaction at all when we need to form a C–C bond.

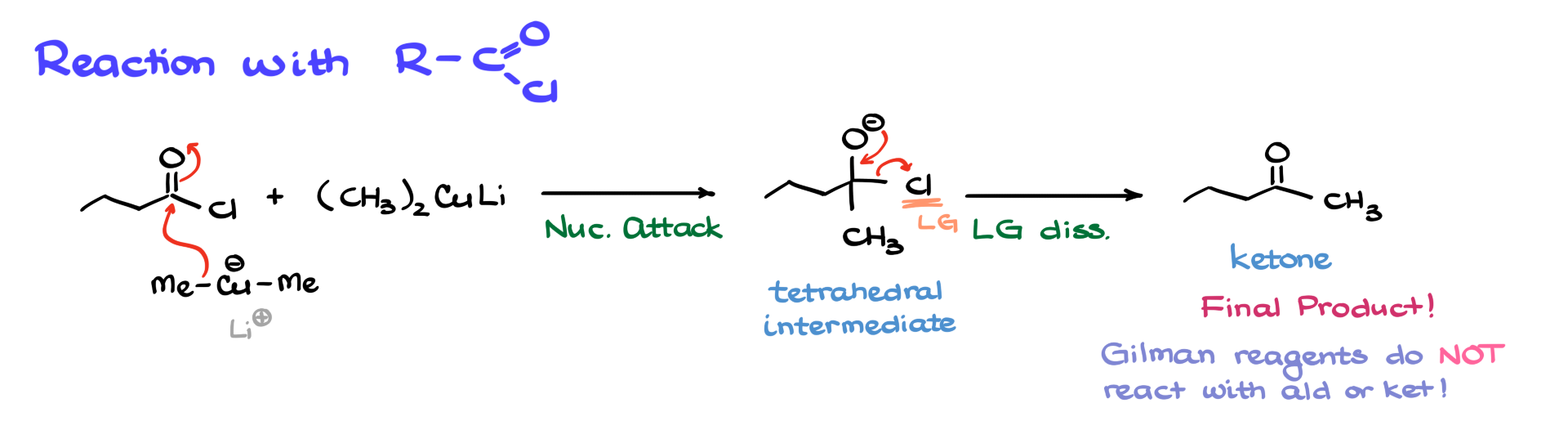

2. Reaction with Acid Chlorides

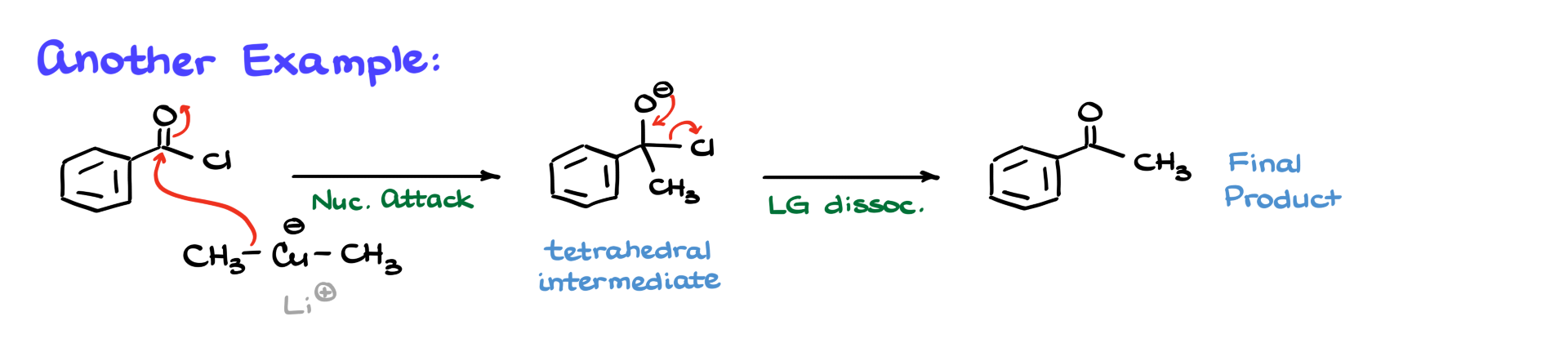

A more useful reaction of Gilman reagents is their reaction with acid chlorides to selectively form ketones.

For example, if we react butanoyl chloride with dimethylcuprate, the nucleophilic methyl group attacks the carbonyl carbon, forming a tetrahedral intermediate. The chloride ion then acts as a leaving group, resulting in the formation of a ketone.

A key advantage of this reaction is that the Gilman reagent stops at the ketone stage. Unlike Grignard reagents, which tend to react further to produce tertiary alcohols, Gilman reagents do not react with ketones. This makes them a useful tool when we need to synthesize ketones selectively.

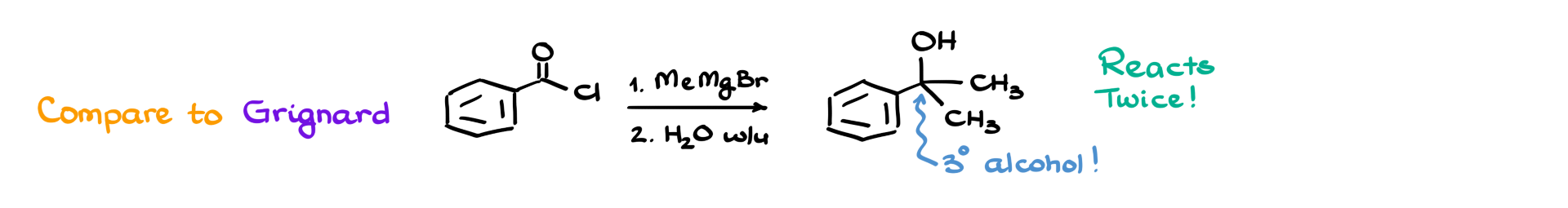

For instance, if we react benzoyl chloride with a Grignard reagent like methylmagnesium bromide, the Grignard reagent will attack twice, producing a tertiary alcohol instead of stopping at the ketone stage. While special conditions can sometimes be used to stop at the ketone, Gilman reagents naturally do so without any extra additives, making them particularly useful in organic synthesis.

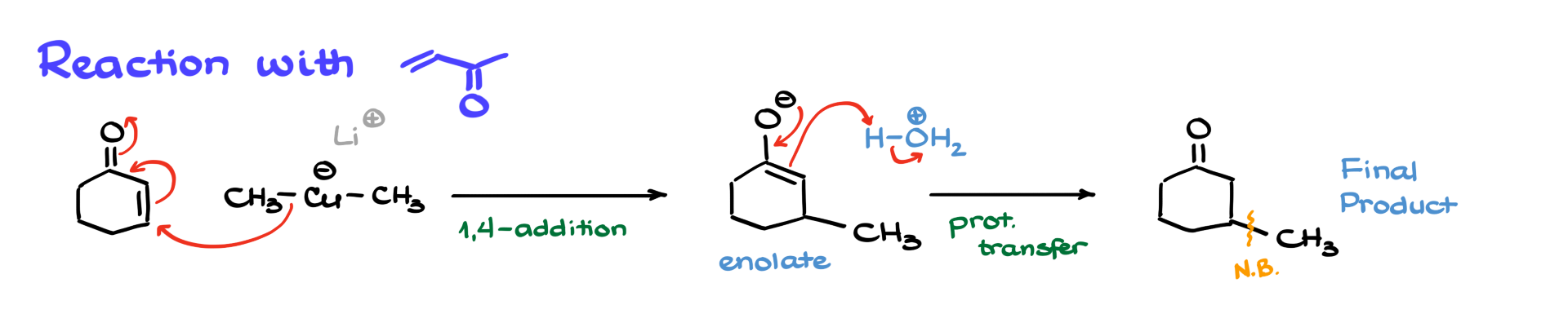

3. Conjugate (1,4) Addition to α,β-Unsaturated Carbonyls

Perhaps the most powerful application of Gilman reagents is their selective conjugate addition to α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds.

For example, when dimethylcuprate reacts with cyclohexenone, the nucleophilic attack occurs at the β-position (the conjugate position), forming an enolate intermediate. After an acidic workup, the enolate is protonated, resulting in a ketone with a new carbon-carbon bond at the β-position.

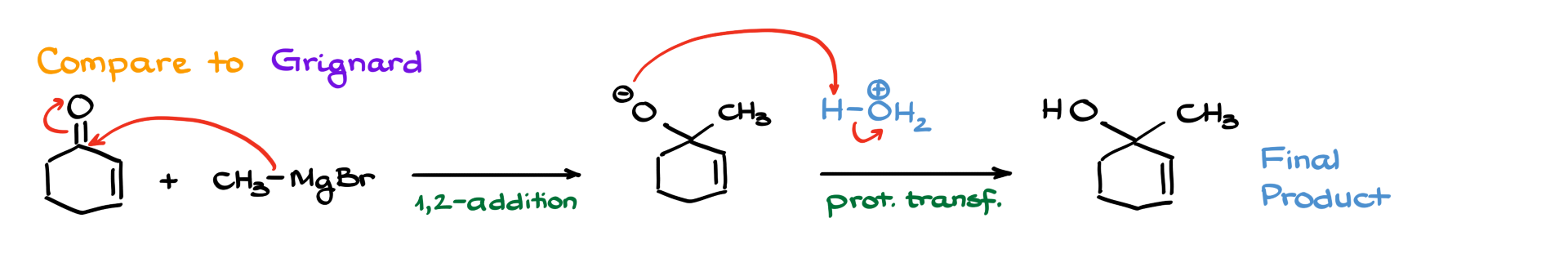

In contrast, Grignard reagents prefer direct (1,2) addition to the carbonyl carbon instead of conjugate (1,4) addition. If we react cyclohexenone with methylmagnesium bromide, the nucleophilic attack occurs at the carbonyl carbon, leading to an alcohol after the acidic workup.

Thus, by choosing between Gilman and Grignard reagents, we can control the site of nucleophilic attack:

• Gilman reagent → 1,4 (conjugate) addition

• Grignard reagent → 1,2 (direct) addition

The same is true for organolithium compounds, which, like Grignard reagents, favor 1,2 addition.

Bonus: Enolate Alkylation Trick

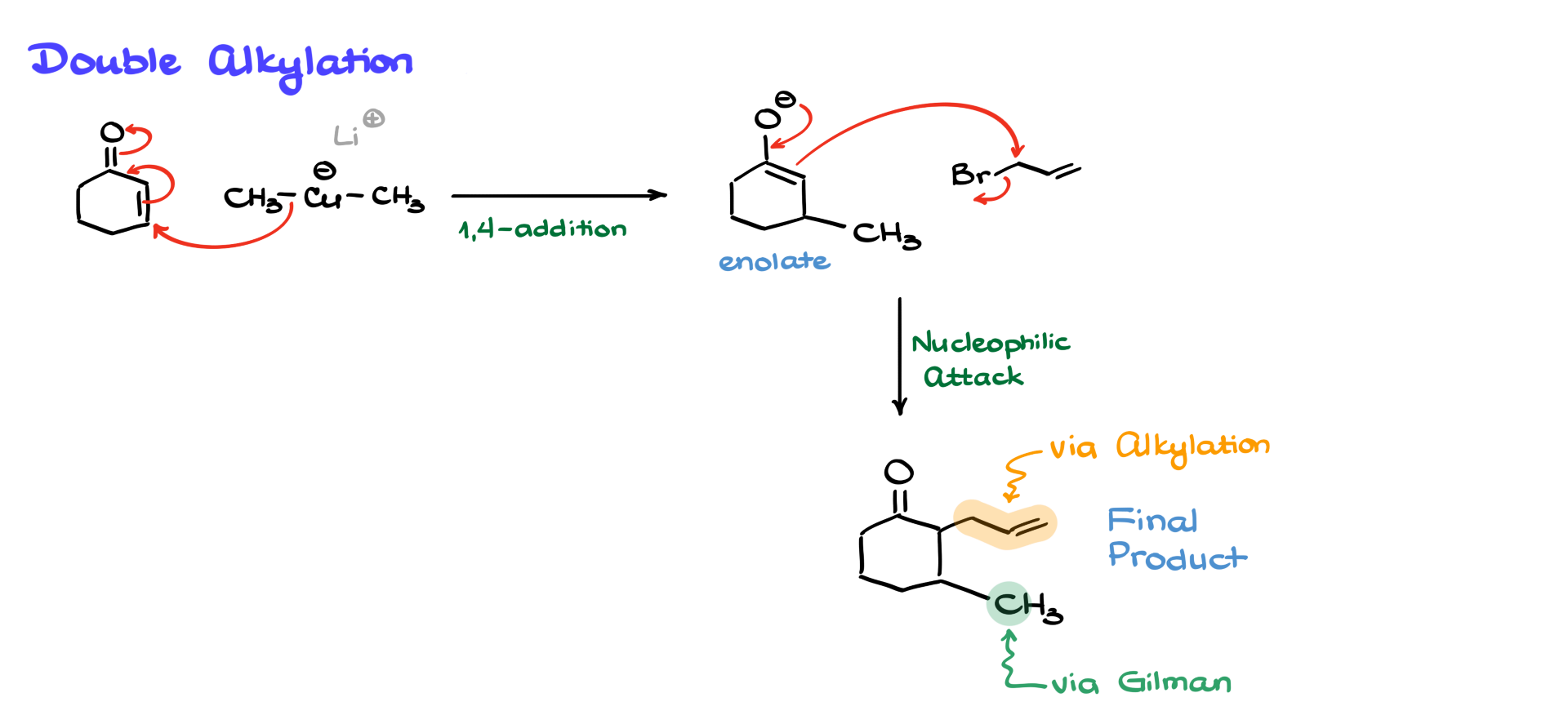

Since the conjugate addition of Gilman reagents creates an enolate intermediate, we can take advantage of this by performing a second alkylation before the acidic workup.

For example, after forming the enolate, instead of immediately protonating it, we can add an alkyl halide (such as bromobutane). The enolate will then react with the alkyl halide in a standard alkylation reaction, adding another carbon-carbon bond in a single synthetic step.

This double alkylation strategy is a useful trick to keep in mind, as it allows us to construct more complex molecules efficiently in fewer steps.

Final Thoughts

Gilman reagents are a powerful tool in organic synthesis. Their mild reactivity makes them useful for selective transformations, including:

• Carbon-carbon bond formation with alkyl halides.

• Selective conversion of acid chlorides to ketones.

• Controlled 1,4 conjugate addition to α,β-unsaturated carbonyls.

So, what do you think about Gilman reagents? Are you ready to use them in your next multi-step synthesis? Let me know in the comments!