Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution in Heterocyclic Compounds

In this tutorial we’re going to go over the electrophilic aromatic substitution in heterocyclic compounds. I have another tutorial on the electrophilic aromatic substitution in regular aromatic compounds, so if you need a refresher, you might wanna start there first.

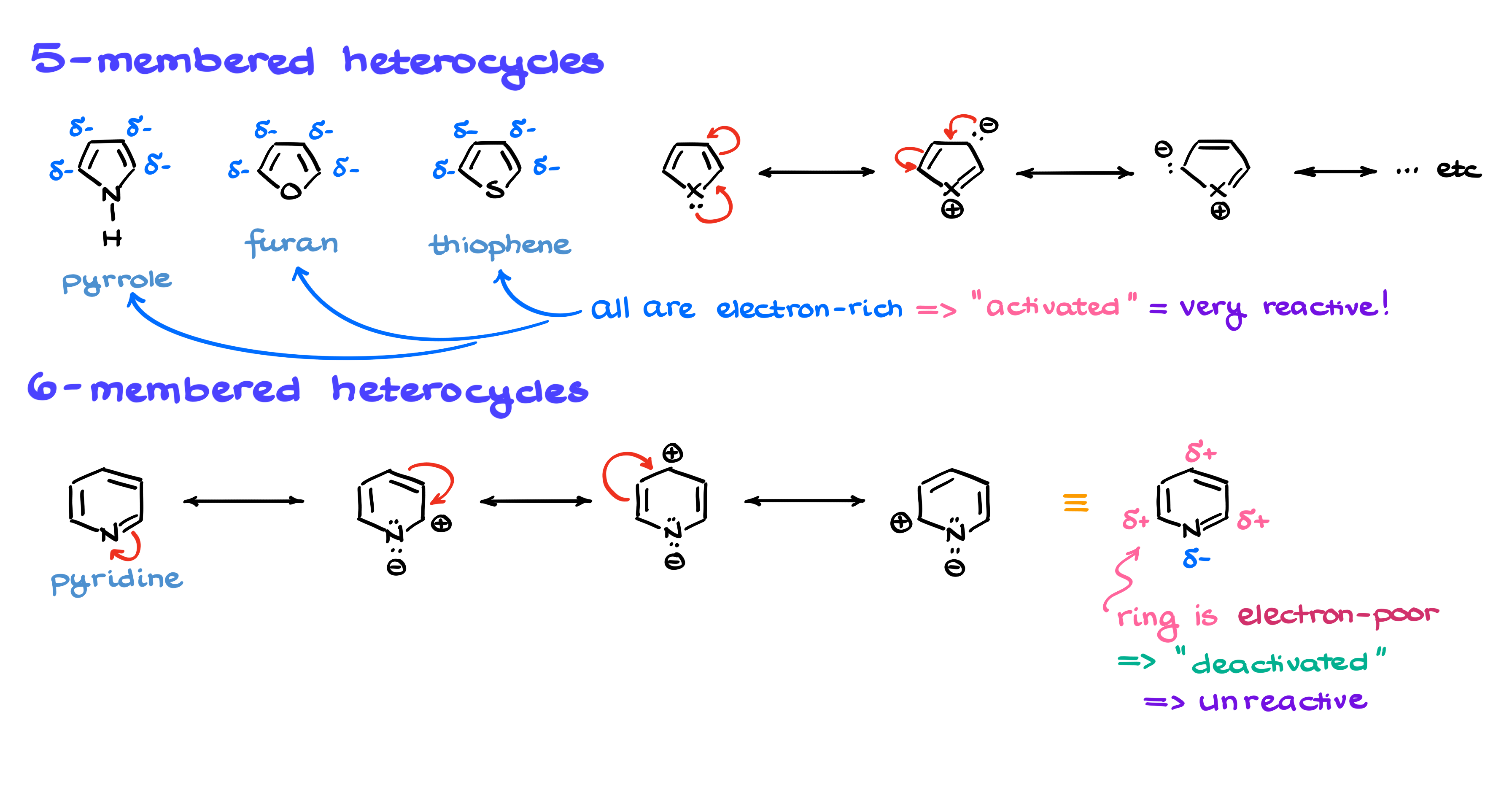

When it comes to electrophilic aromatic substitution in heterocycles, you’ll most commonly encounter five- and six-membered rings. Among the five-membered rings, the most common ones are pyrrole, furan, and thiophene. I’ll represent all of them collectively as a five-membered ring with an “X,” where X is the heteroatom.

For six-membered rings, there are several possible options, but in practice, the one you’ll most often see is pyridine. Regardless of whether we’re dealing with regular aromatics or heterocyclic compounds, the key to understanding their reactivity lies in resonance.

Let’s start with a five-membered heterocycle and draw some resonance structures. If I take the lone pair on the heteroatom and move it around, I get a set of resonance contributors. From there, I can shift the electrons again, generating another contributor. I can also do this in the opposite direction, producing another set of contributors. The important takeaway from these structures is that the electron density is concentrated on certain carbons in the ring, meaning these molecules are electron-rich.

Using electrophilic aromatic substitution terminology, these rings are activated, making them highly reactive toward electrophiles.

Now, if we look at a six-membered ring like pyridine, we can analyze its resonance as well. However, due to the electronic configuration of this system, the heteroatom actually pulls electron density toward itself. When I start drawing resonance structures, I see that instead of having partial negative charges on the ring carbons, I now have partial positive charges. This makes the ring electron-poor, meaning it is deactivated for electrophilic aromatic substitution and largely unreactive.

In fact, pyridine is so unreactive in these reactions that it can actually be used as a solvent in typical electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions without interfering. That’s how deactivated it is.

EAS in 5-Membered Rings

But reactivity isn’t the only thing we need to consider—we also need to determine where exactly the reaction occurs. In other words, we need to think about the regioselectivity of the substitution.

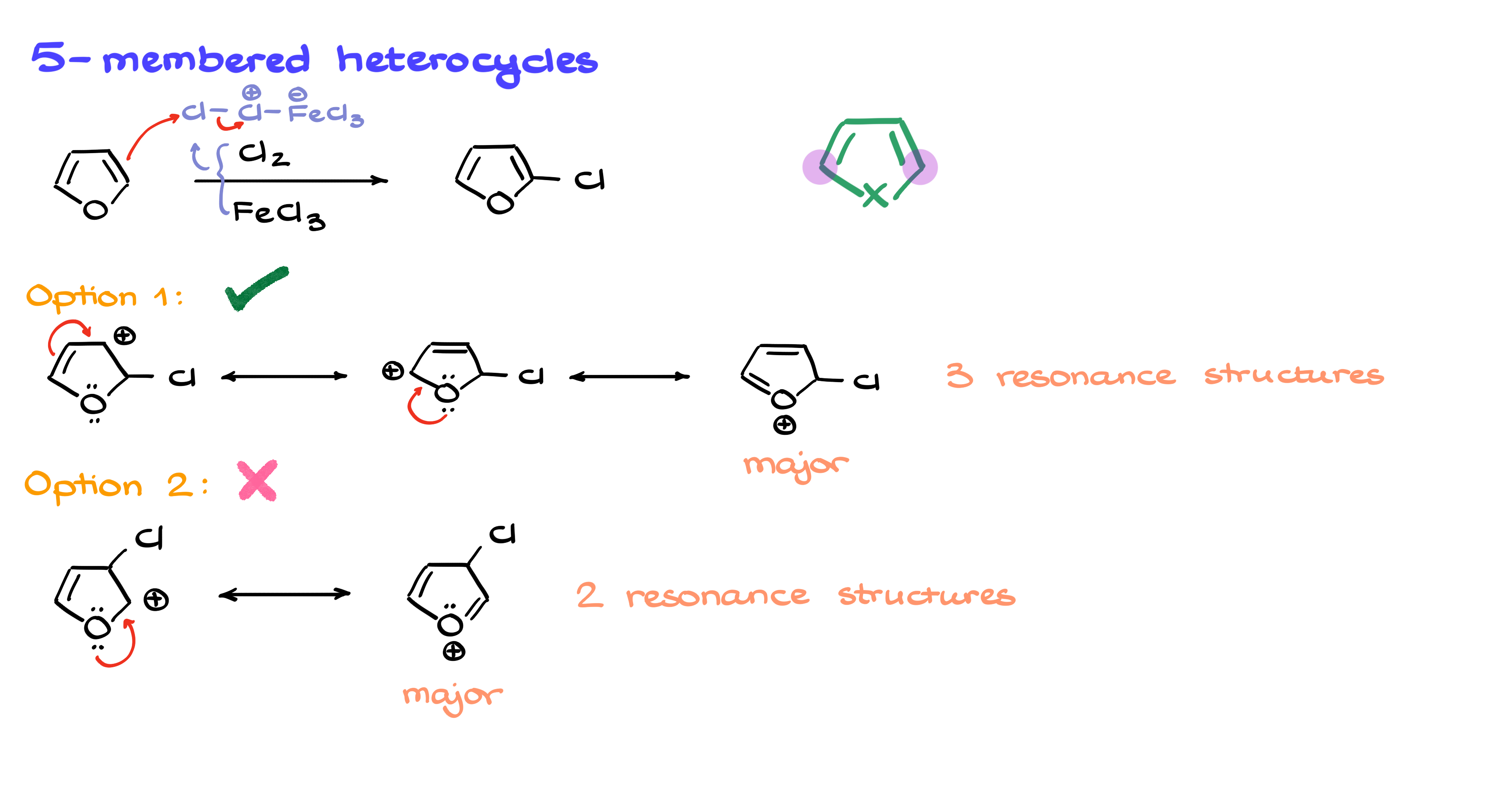

Let’s go back to a five-membered ring and run through a typical electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction—halogenation. The first step in any halogenation reaction is the formation of the electrophile, which in this case looks like this. Once that electrophile attacks the aromatic ring, we have two possible sites where the substitution can occur.

In the first case, the chlorine adds to the position right next to the heteroatom. If I start drawing resonance structures for this intermediate, I can see that the lone pair on the heteroatom helps stabilize the carbocation through resonance, giving me three viable contributors.

In the second case, chlorine attaches to a position further from the heteroatom. Drawing resonance structures for this intermediate, I see that there are only two reasonable contributors. Since the stability of an intermediate is influenced by the number and quality of resonance structures, the first option, with three contributors, is more stable. This means that our final product will have chlorine at the more stabilized position.

So in five-membered heterocycles, substitution typically occurs at these preferred positions. Of course, if the molecule has additional substituents, they may influence regioselectivity, so a more detailed analysis might be needed. But in the simplest case, this is what we expect to see.

EAS in 6-Membered Rings

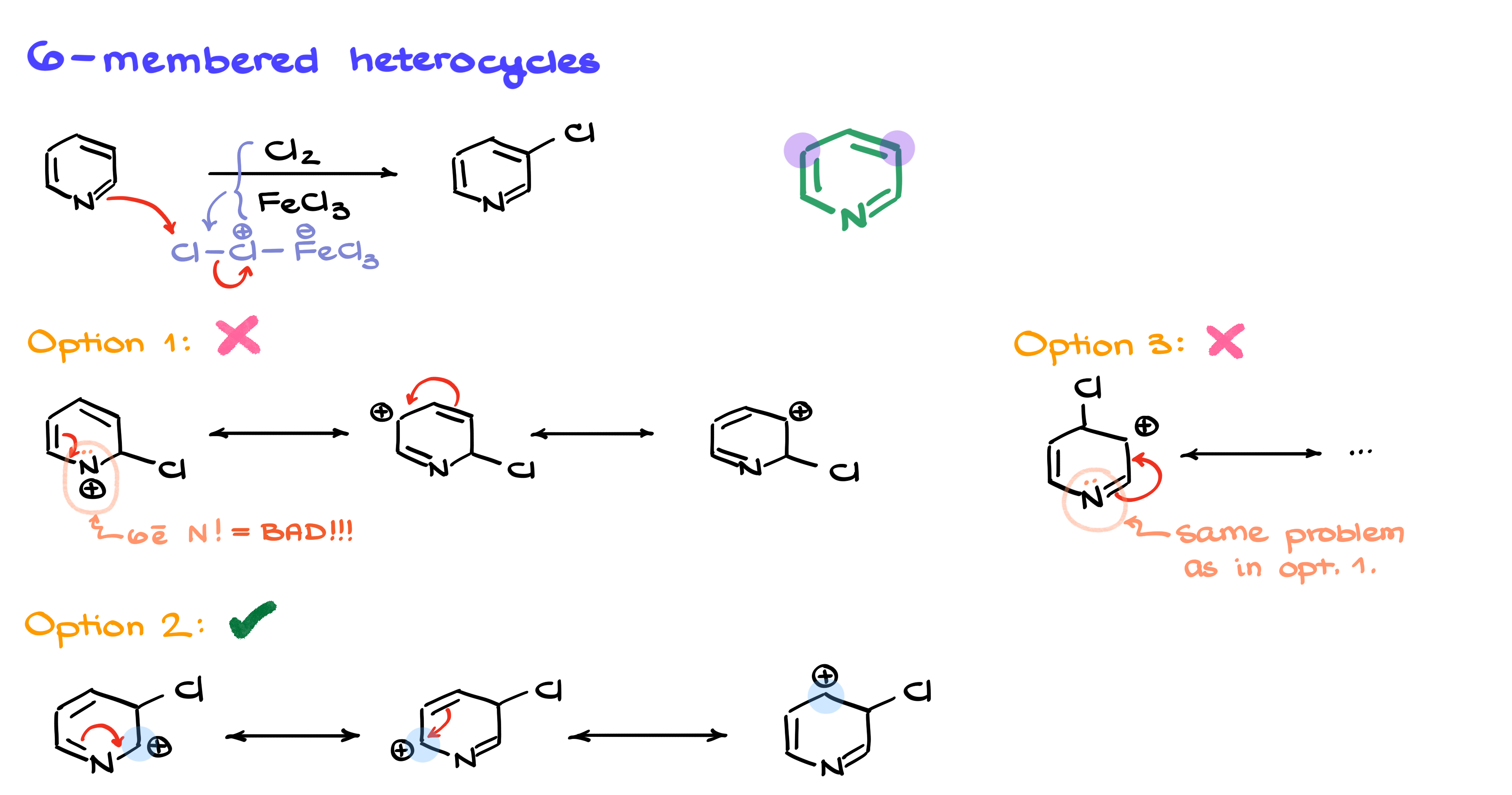

Now let’s move on to a six-membered ring, such as pyridine. Running through the same reaction, we first generate our electrophile, and then it can attack the ring at three possible positions.

The first option is for the electrophile to add to the position directly adjacent to the nitrogen. If I draw resonance structures, I quickly see a problem—one of the contributors places a formal positive charge on nitrogen. This is highly unstable because nitrogen is electronegative and strongly disfavors an open-shell, six-electron configuration. This means the entire resonance set is destabilized, making this substitution site very unfavorable.

The second option is for the electrophile to add one position further from the nitrogen. Drawing the resonance structures, I see that while the intermediates are still not ideal, they are significantly more stable than the first option because they don’t generate a highly unstable nitrogen cation.

The third option places the electrophile even further away, but unfortunately, it leads to the same problem as the first case—creating an unstable nitrogen cation. So this option is also unfavorable.

Since the second option is the most stable among the three, the electrophilic substitution occurs at this position, meaning our final product will have the halogen added at this site.

In summary, for five-membered rings, substitution occurs at positions that maximize resonance stabilization, while for six-membered rings like pyridine, substitution tends to occur at the third position relative to nitrogen to avoid highly unstable intermediates. If additional substituents are present, they can influence the directing effects, so always analyze the resonance structures carefully.