Corey-Chaykovsky Epoxidation

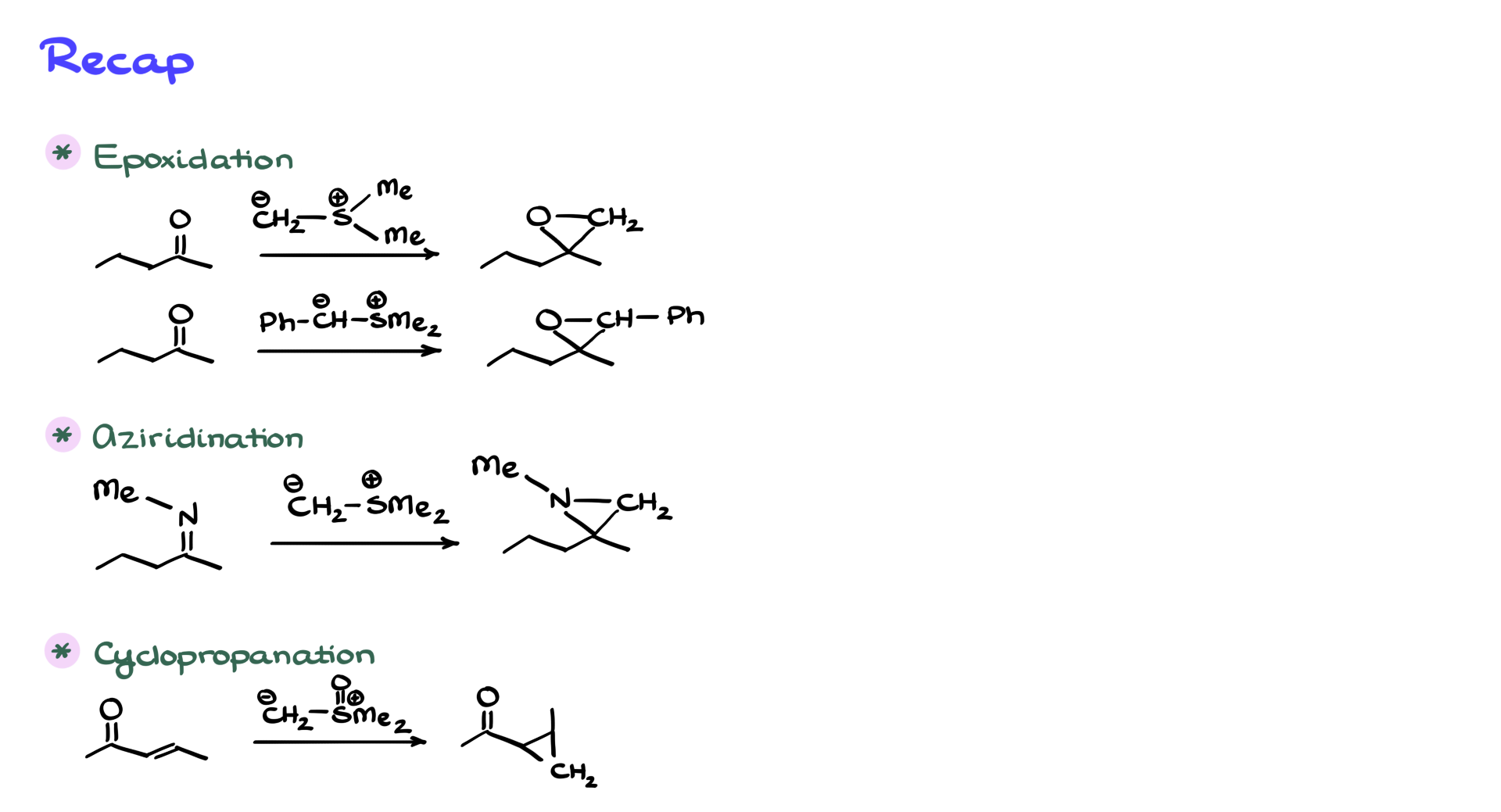

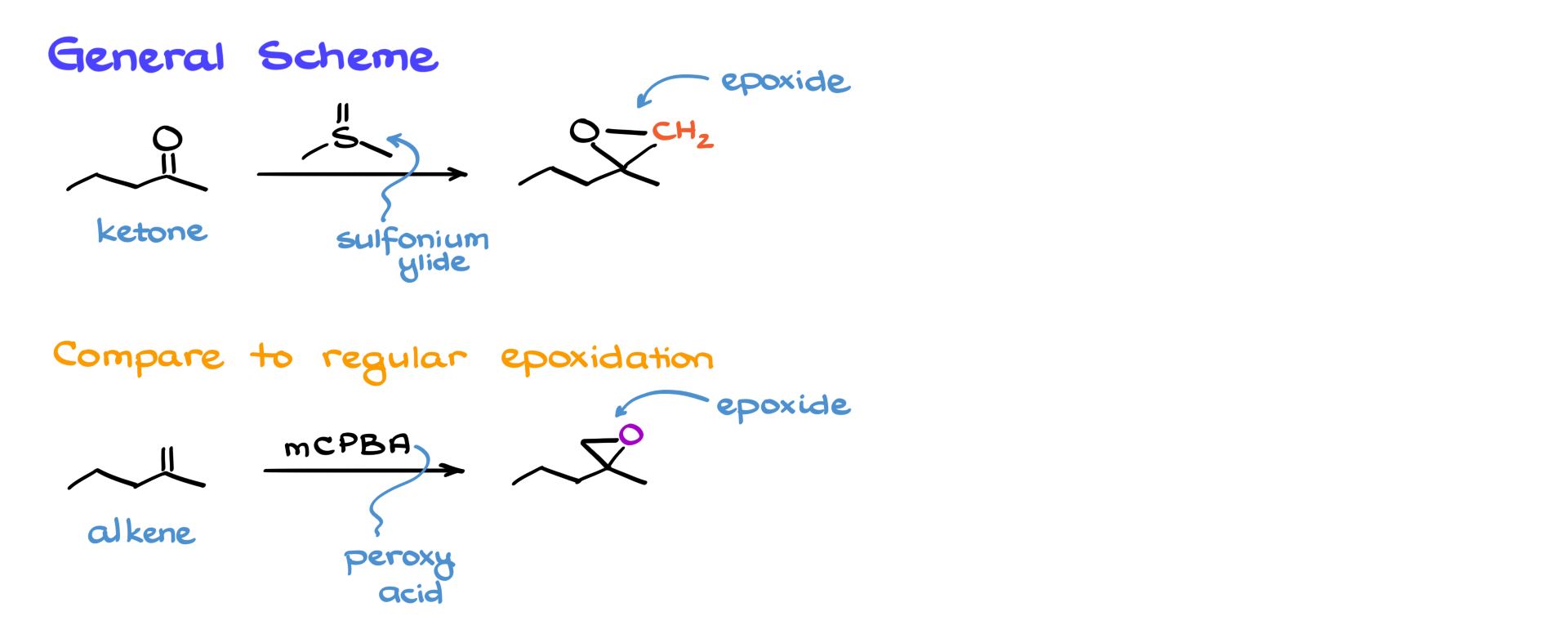

In this tutorial, I want to talk about a useful epoxidation reaction called the Corey–Chaykovsky reaction. Generally speaking, when we’re dealing with the Corey–Chaykovsky, we start with a ketone and treat it with a sulfonium ylide.

As a result of this interaction, we get an epoxide. Now, compared to a regular epoxidation using a peroxy acid like mCPBA, the major difference is that in the traditional case, we typically start with an alkene—not a ketone. However, both reactions can potentially give you the exact same product. So the important thing here is understanding the applicability of each reaction and how well each tolerates other functional groups that might be present in your molecule.

Mechanism of the Corey-Chaykovsky Reaction

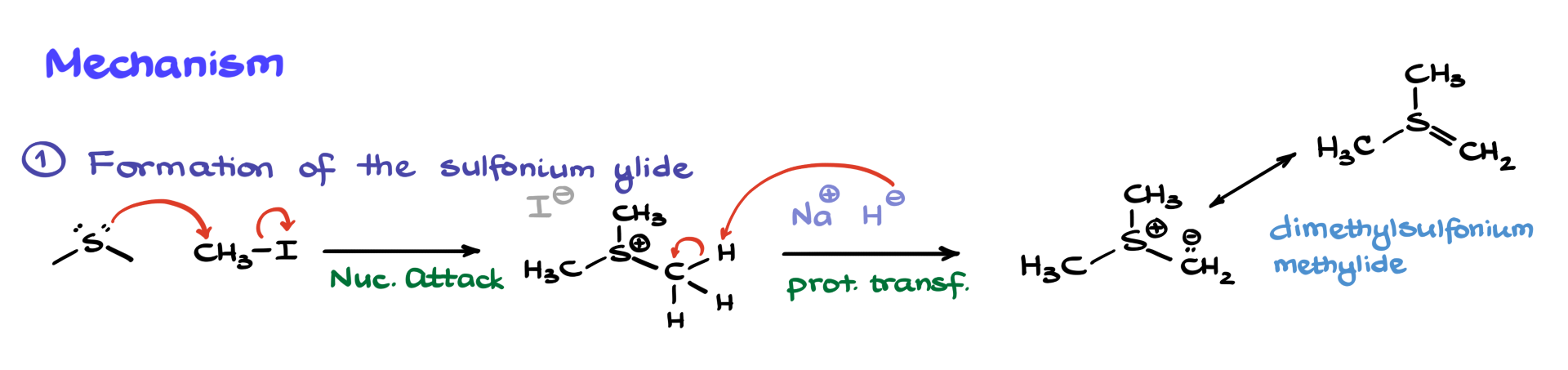

Now that we’ve got a general idea of what the Corey–Chaykovsky reaction is, let’s look at the mechanism. There are two main phases.

First, we start by forming our sulfonium ylide. Typically, we begin by taking dimethyl sulfide and reacting it with a simple electrophile, like methyl iodide. That’s going to be a classic SN2 reaction, giving us an intermediate. This positively charged intermediate is called trimethylsulfonium iodide—not that the name is super important, but just FYI.

Once we’ve got this intermediate, we treat it with a base. Often, it’s a strong base like sodium hydride, although other versions can show up in the literature depending on the specific molecule. And since I need to show a proton transfer here, I’ll redraw the CH₃ group to show all the hydrogens so we can follow the hydride pulling a proton off. This gives us the next intermediate: dimethylsulfonium methylide—or just sulfonium ylide, which is what I’ll call it going forward. As we’ll see later in this tutorial, there are other ylides that can be used too, so this one isn’t the only player in the Corey–Chaykovsky game.

Before diving into the carbonyl reaction, I want to point out that this ylide has another resonance form that you might see in textbooks or literature, where there’s a double bond between sulfur and carbon. Even though that’s actually a minor resonance contributor (we know from research that there isn’t really a sulfur–carbon double bond), it still shows up all the time in the literature, so don’t be surprised if that’s what you see.

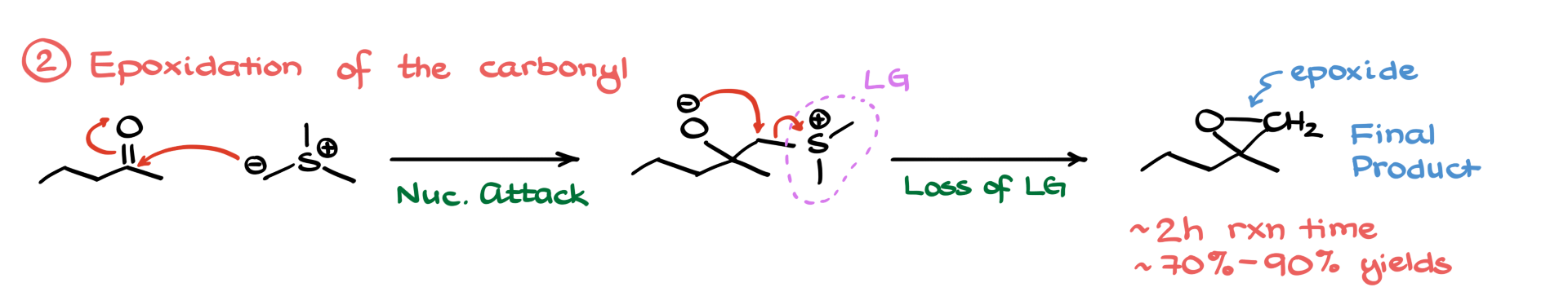

Now, back to the reaction. The next step is the interaction with a carbonyl—just a simple ketone in this case. I’ll draw that, along with my sulfonium ylide, showing the charges to make it easier to follow. From here, we have a straightforward nucleophilic attack where the nucleophilic carbon from the ylide attacks the carbon of the carbonyl, giving us an intermediate.

Here’s where it gets fun: the sulfur part—the dimethylsulfonium group—acts like a leaving group. Oxygen attacks the carbon, kicks that group out, and boom: we get our final product, which is the epoxide. While the reaction might take a couple of hours to go to completion, it typically gives really good yields. So be patient—it’s worth it.

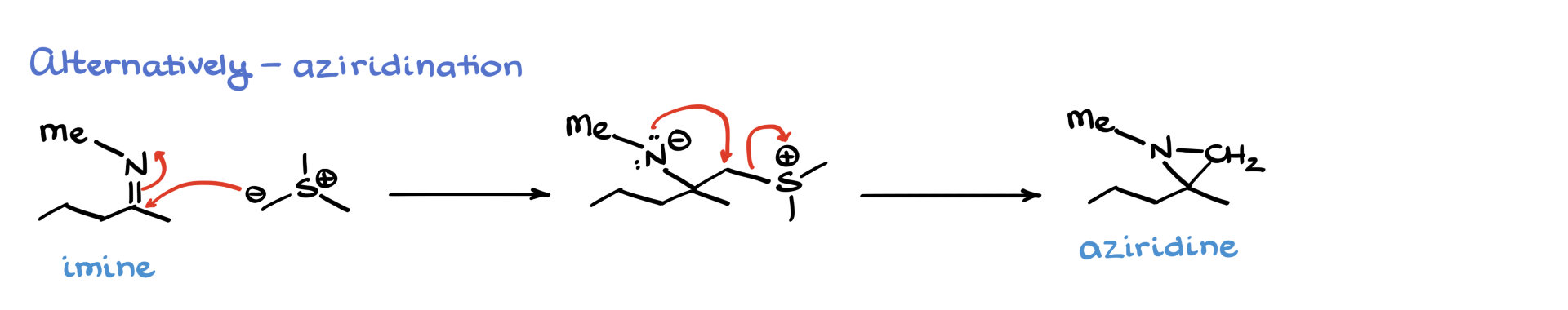

Aziridination Reaction

Now, an interesting feature of our sulfonium ylide is that it also reacts with other polar double bonds.

For example, take an imine. We’ve got a polar C=N bond there, and if we bring it into contact with our ylide, we get a very similar reaction. The nucleophilic ylide attacks the carbon of the imine’s double bond, gives us a similar intermediate, and then nitrogen attacks the carbon in an intramolecular fashion, kicking out the leaving group and forming a new three-membered ring. This one’s called an aziridine.

So when people call the Corey–Chaykovsky reaction an epoxidation, they’re actually selling it short—it doesn’t just make epoxides. It can also make aziridines. While that might not show up in an intro organic course, it’s totally fair game in advanced organic, and knowing how to make aziridines can be super handy.

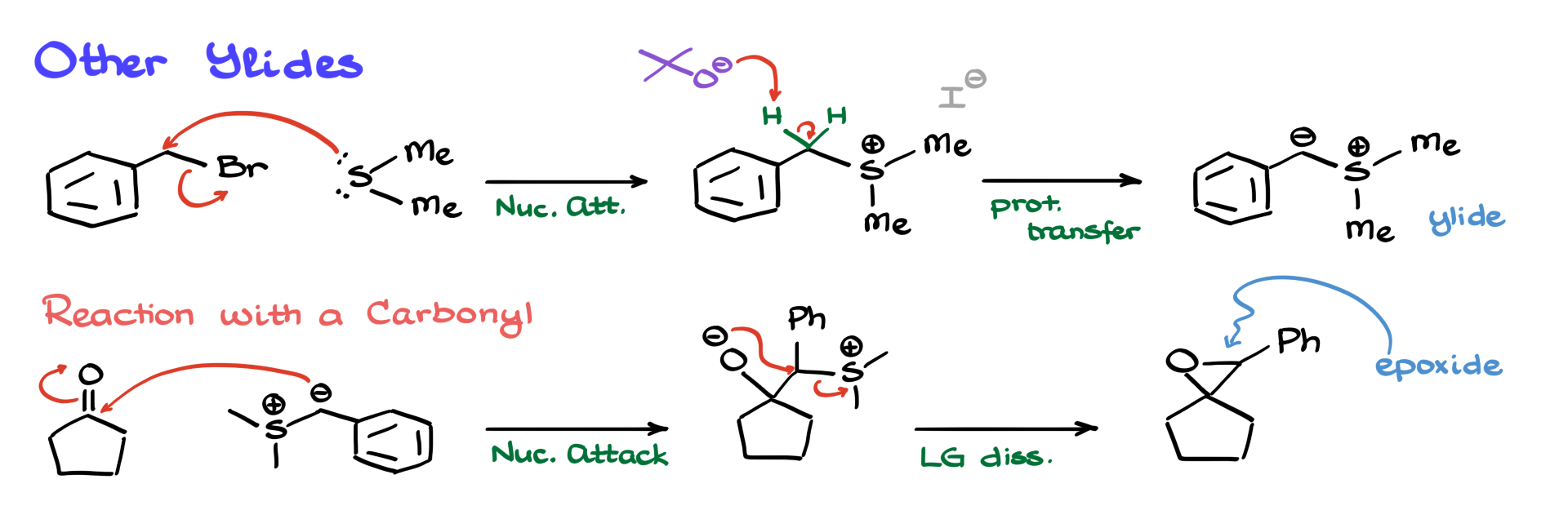

Other Ylides

As I mentioned earlier, dimethylsulfonium methylide isn’t the only possible ylide. We can use other variants too.

For instance, let’s say we start with benzyl bromide. We treat it with dimethyl sulfide, just like before. Sulfur attacks the carbon, kicks out the bromine, and we get a sulfonium ion—specifically, benzylsulfonium iodide.

Here’s the twist: if the molecule has hydrogens that are more acidic than those on the methyl groups—like the benzylic hydrogens in this case—we can deprotonate those selectively. They’re more acidic due to resonance stabilization from the aromatic ring, so we don’t need a super-strong base. Something milder, like tert-butoxide, will do. The base pulls the proton, and we get the new ylide.

Now we take that ylide and react it with a carbonyl—say, cyclopentanone. The reaction goes as expected: nucleophilic attack, intermediate forms, oxygen attacks, leaving group leaves, and we get the corresponding epoxide. This time, though, we’ve added a whole new group to the molecule, which is a huge bonus from a synthetic standpoint. Fewer steps, more complexity—win-win.

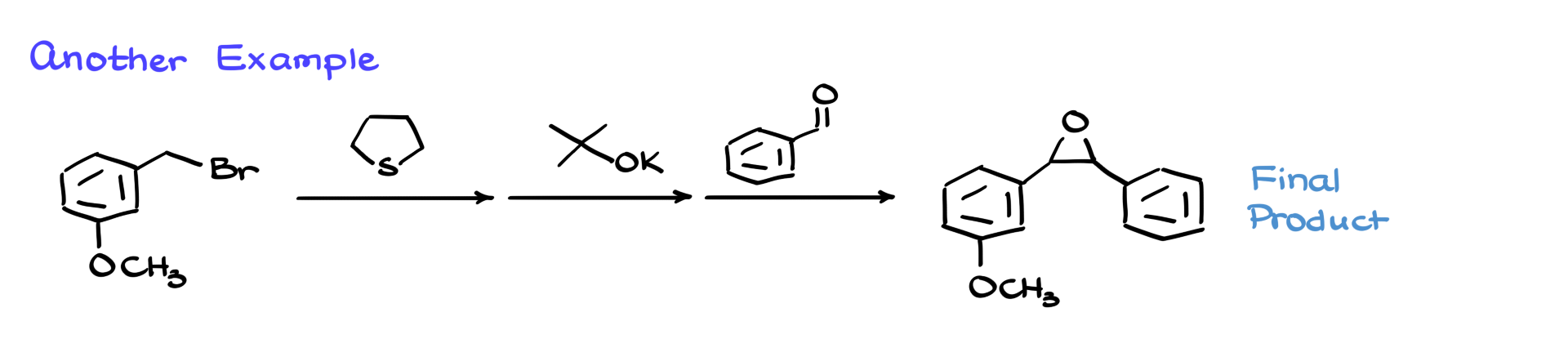

Let’s take another example. We start with a different bromide and react it with a different sulfide—tetrahydrothiophene instead of dimethyl sulfide. The process is still the same: react to form the sulfonium ion, treat with base to get the ylide, bring in the carbonyl (benzaldehyde in this case), and get a complex epoxide. I’m not showing the full mechanism here, but it’s worth trying to draw it out and see if you can reach the final product.

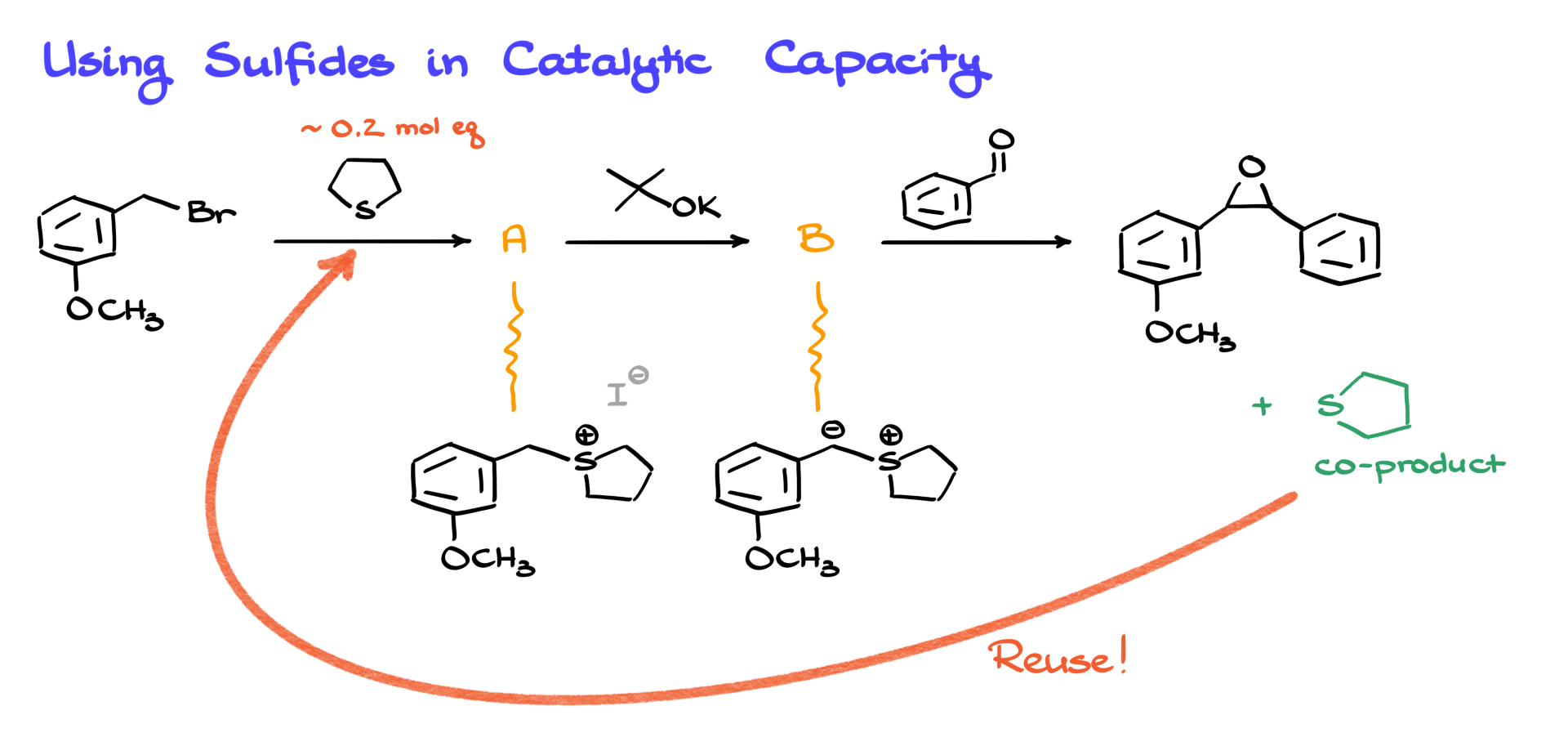

Catalytic Version

Now, if you’ve ever worked with organosulfur compounds, you know how stinky they are. Seriously, it’s a torture. So, ideally, we’d use them in catalytic amounts to limit exposure. And luckily, with this mechanism, we can sometimes do just that. After forming the sulfonium iodide and treating it with a base to get the ylide, if you trace through the last steps, you’ll notice the reaction regenerates the original sulfide. So we can reuse it and run the whole thing as a one-pot process. That way, we only need a small amount of sulfide—enough to stink up the room, not the whole neighborhood.

Of course, this doesn’t work in every variation. It only works when the nucleophilic attack from your base on the alkyl halide isn’t problematic. But when it does work—it’s awesome.

Oxosulfonium Ylides

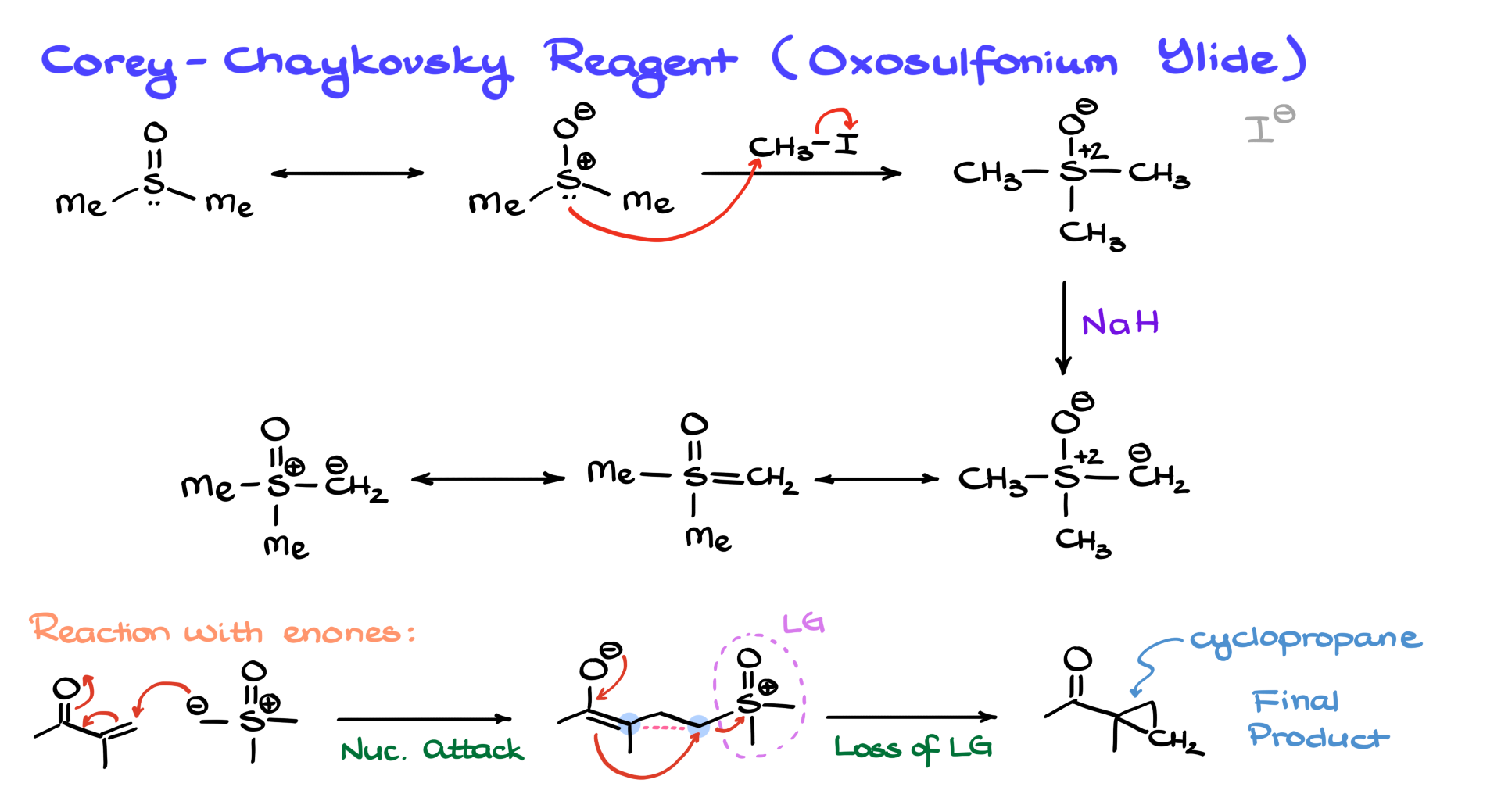

Now, let’s talk about another ylide variant: the oxosulfonium ylides, also known as Corey–Chaykovsky reagents. These reactions are usually done in DMSO, whose structure you probably know. There’s a resonance form of DMSO with a positive charge on sulfur and a negative charge on oxygen—that’s actually the major contributor. But traditionally, we draw it with a sulfur–oxygen double bond.

If we heat DMSO with methyl iodide for a long time, we get a slow reaction where sulfur acts as the nucleophile, kicking out the iodide and giving us a sulfonium salt. Again, this can be drawn either with formal charges or a double bond, depending on your preference or what you see in the literature. After that, we treat it with a strong base, pull a proton from the methyl group, and get the oxosulfonium ylide.

We can draw this with formal charges, or sometimes with resonance forms—like the kind where sulfur appears to have two double bonds (even if that’s not entirely accurate). These oxosulfonium ylides are more stable and less reactive than their regular counterparts. If you’re into hard and soft acid-base theory, you’d say this is a softer nucleophile.

What’s really cool is that these softer nucleophiles prefer to react with α,β-unsaturated carbonyls—enones. So if we draw one of those, our oxosulfonium ylide can do a conjugate (Michael-type) addition. Instead of attacking the carbonyl carbon, we attack the β-position. That gives us a new intermediate, and from there, our enolate kicks out the leaving group, forming a new C–C bond and giving us a cyclopropane.

So, as you can see, the Corey–Chaykovsky reaction loves making three-membered rings. Epoxide formation is just one of its many talents. To sum it up, we can use this reaction to make simple or complex epoxides, aziridines if we start with an imine, or cyclopropanes if we use an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl and an oxosulfonium ylide.