Cope Rearrangement

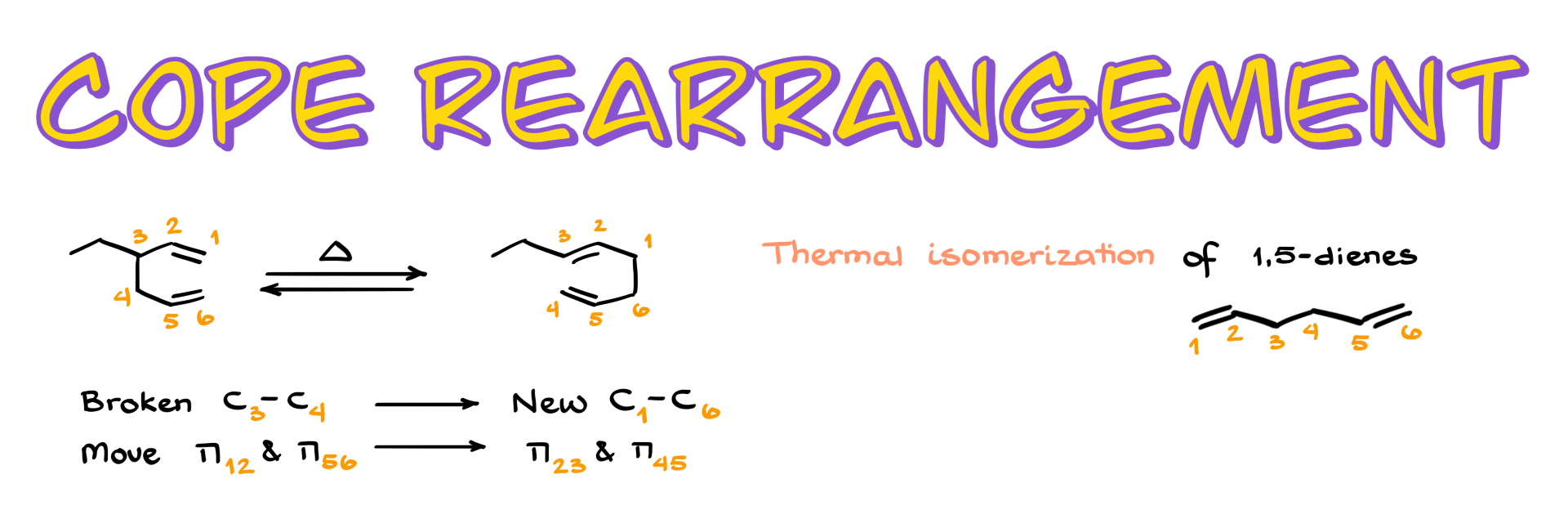

In this tutorial, I want to talk about the Cope rearrangement, which is a thermal isomerization of 1,5-dienes. This means that virtually any molecule with that basic structure of a 1,5-diene—so long as it can fold into a ring-like conformation—has the potential to undergo a Cope rearrangement.

When looking at the starting material, the key atoms involved in the reaction are carbons 1 through 6. This portion of the molecule is what actually undergoes transformation, while everything else is mostly just substituents and doesn’t really matter for the core reaction. To make it easier to track what’s going on, I’ve also numbered the atoms in the product. That way, you can clearly see that we’re breaking the bond between carbons 3 and 4 in the original molecule and forming a new bond between carbons 1 and 6. The π bonds also shift position—from being between carbons 1 and 2 and 5 and 6, to now sitting between carbons 2 and 3 and 4 and 5. So essentially, you’re flip-flopping the single and double bonds across the ring.

Mechanism of the Cope Rearrangement

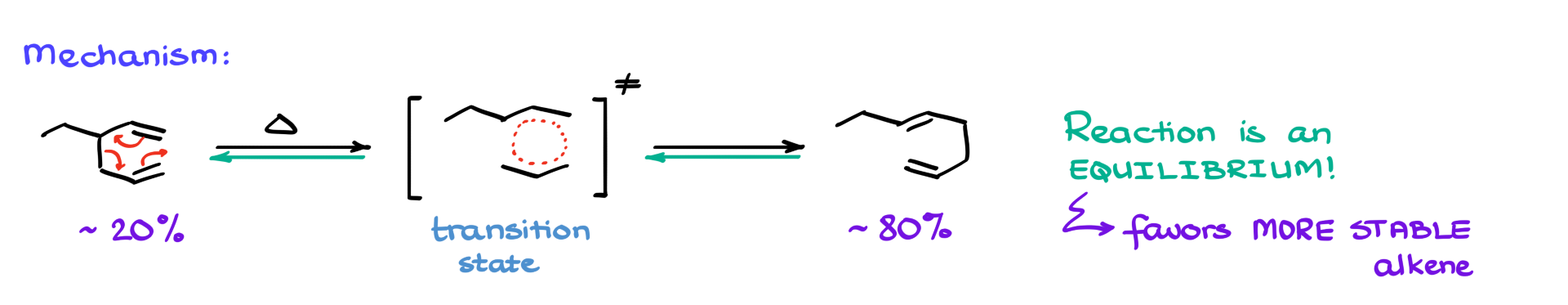

Mechanistically, this is a pericyclic reaction, meaning the transition state is cyclic. And as far as curved arrows go, it really doesn’t matter if you draw them clockwise or counterclockwise—it’s the same movement of electrons around the ring.

An important aspect of the Cope rearrangement is that it’s an equilibrium reaction. So, you don’t just end up with the product—you get both starting material and product in equilibrium. The reaction typically favors the more thermodynamically stable alkene, so you’ll often see a product-to-reactant ratio around 5:1 or 6:1, depending on the specific stabilities involved. For instance, in the example here, the product has one double bond with two substituents and another with just one, making that more substituted bond more stable. So naturally, the product is favored in equilibrium.

Examples of the Cope Rearrangement

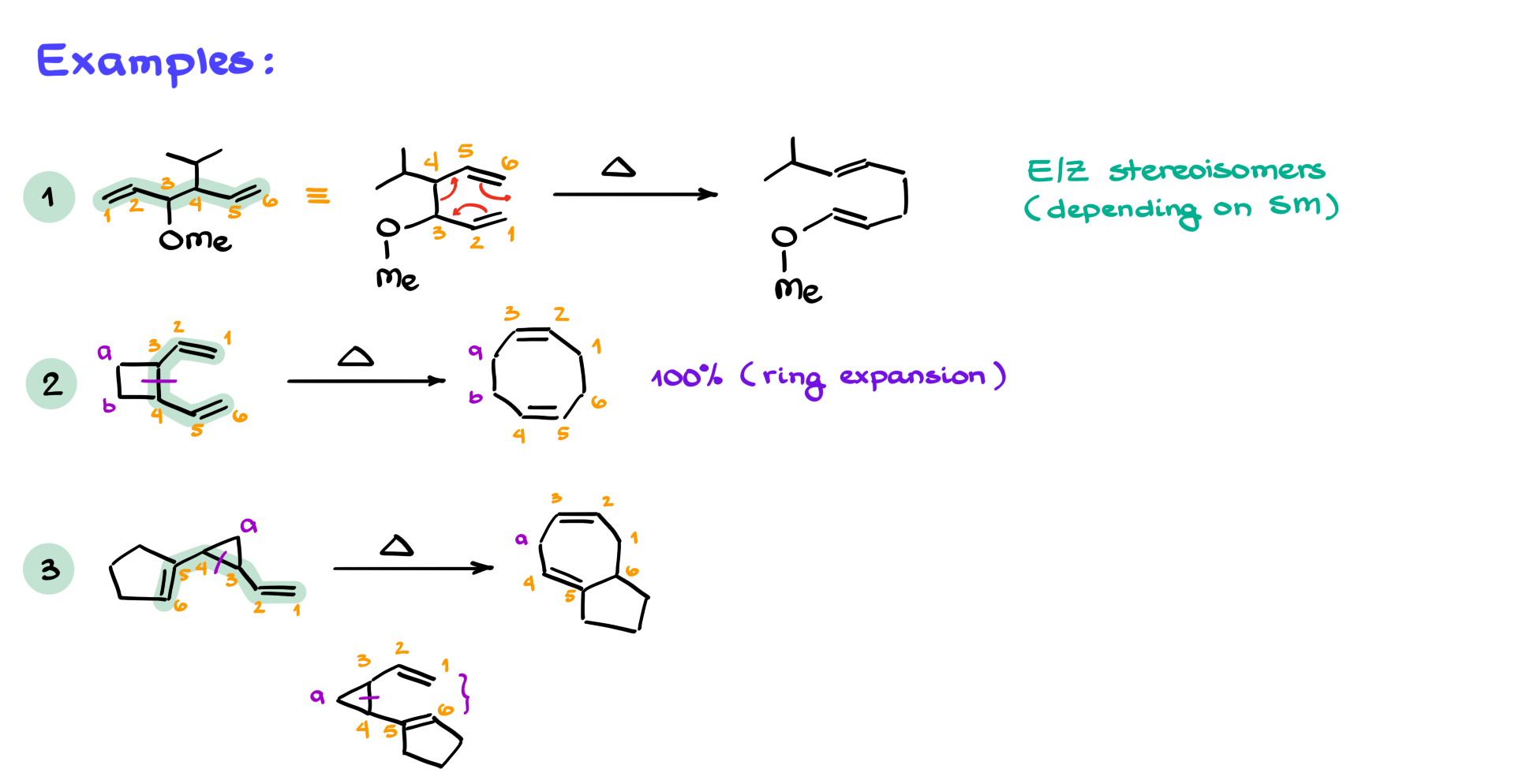

Now let’s consider a more test-like example.

You might be shown a molecule that doesn’t obviously look like a 1,5-diene, but if you trace the backbone and number your chain, you might find that the double bonds are indeed sitting on carbons 1 and 5. That makes it a 1,5-diene, even if it’s not drawn in the “classic” form. If that open-chain molecule can curl into a six-membered transition state, the Cope rearrangement can proceed. Redrawing the structure in a cyclic form helps visualize the atoms and the shifts. You still break the 3–4 bond, form the 1–6 bond, and migrate the π bonds. In this case, the product has two double bonds, each with two substituents—more substituted and more stable than the starting material.

Now, stereochemistry. Yes, E/Z isomerism can be present in these types of molecules, but for the purposes of this tutorial, we’re not diving deep into stereochemistry. Most introductory organic chemistry courses don’t emphasize it for this reaction. That said, advanced courses will absolutely expect you to be able to account for stereochemistry, especially when studying pericyclic reactions in detail.

Let’s look at a more complex example now. One of the really interesting applications of the Cope rearrangement is in forming larger rings. Take a strained four-membered ring. If there’s a way for it to open up through a Cope rearrangement, it absolutely will—because that release of strain is energetically favorable. In the example shown, if you identify the 1,5-diene unit, number the atoms 1 through 6, and then identify the extra atoms of the four-membered ring as A and B, you’ll be able to track the transformation. You break the bond between atoms 3 and 4, form a new one between 1 and 6, and end up with an 8-membered ring. This is a reaction that gives near-complete conversion to the product due to the strain release.

Oxy-Cope Rearrangement

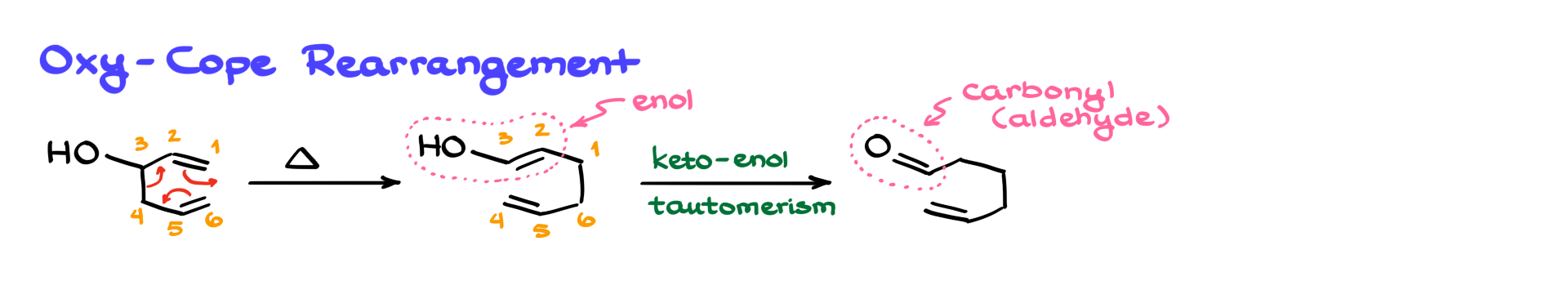

Another variation that’s especially powerful is the oxy-Cope rearrangement.

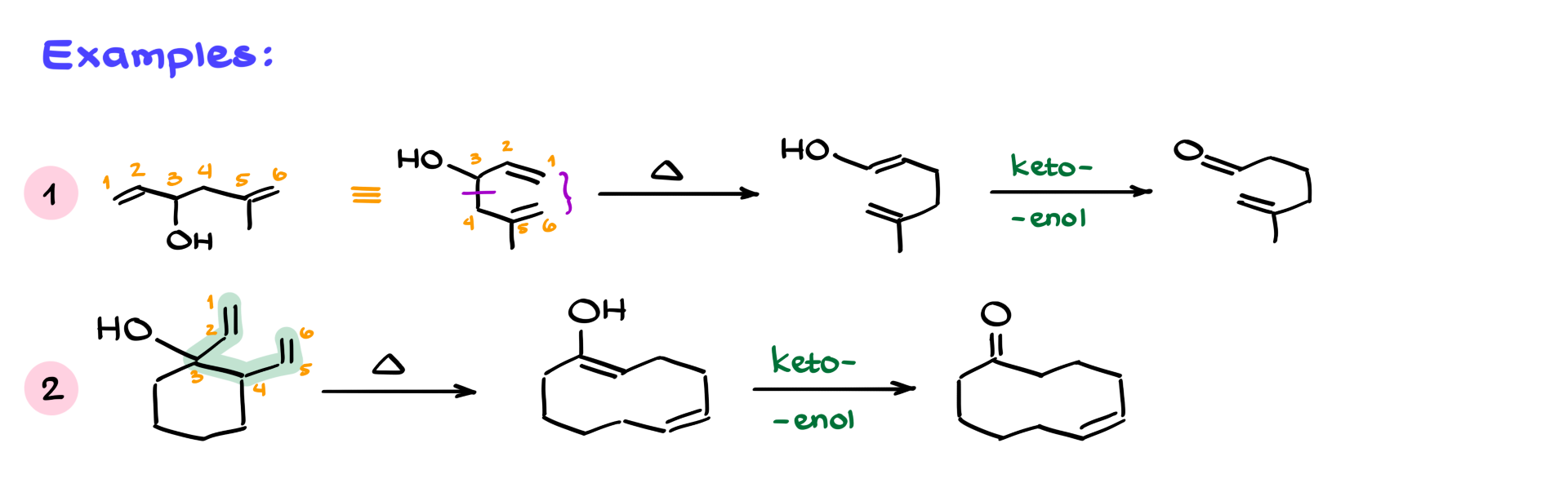

In this version, if you have a hydroxyl group on carbon 3, the reaction proceeds just like the regular Cope rearrangement with the same cyclic transition state. The key difference comes after the rearrangement—because now you’ve formed an enol as part of your product. Enols are unstable and will tautomerize into carbonyl compounds, like aldehydes or ketones. And because this tautomerization favors the carbonyl under typical conditions, it pulls the reaction equilibrium forward, giving you the carbonyl product almost exclusively, regardless of the alkene stability in the intermediate.

For instance, in a molecule with a hydroxyl on the third carbon and a 1,5-diene structure, redrawing it in a more cyclic form makes it easier to see how the rearrangement plays out. After breaking and forming the proper bonds and flip-flopping the π bonds, you get an enol intermediate, which quickly tautomerizes to an aldehyde. Here, the double bond stability isn’t really important—what matters is that the reaction ends with a stable carbonyl.

One more example that really shows off the synthetic utility of the oxy-Cope rearrangement involves forming a 10-membered ring. These are notoriously difficult to synthesize using other methods. But with the oxy-Cope, you can take a molecule that might not look like your typical Cope starting material, identify the 1,5-diene and OH on the third carbon, and then walk through the same steps—form the 1–6 bond, break 3–4, shift your π bonds. You get an enol, which tautomerizes to a carbonyl, and voilà—a 10-membered ring that would otherwise be a major synthetic challenge.

So, whether you’re working with the classic version or the oxy variation, the Cope rearrangement is an incredibly powerful reaction. It’s been used extensively in total synthesis and the creation of industrial and medicinally important molecules because of its ability to build complex ring systems in a relatively straightforward manner.