Cascading Claisen into Cope Mechanism Challenge

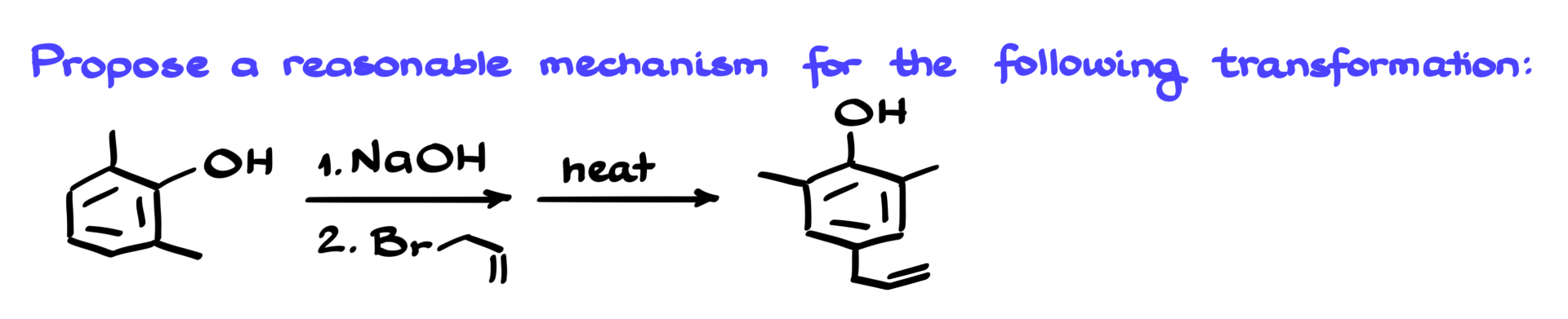

In my Claisen rearrangement tutorial, I gave you this question at the end as a challenge. So let’s break down the mechanism together now.

I’m going to start by redrawing the starting material and adding sodium hydroxide. The sodium is just a counterion here, so it’s not that important—what really matters is the hydroxide, which acts as the base. Since phenols are somewhat acidic, the first step is a simple acid-base reaction. The hydroxide ion comes in, pulls off the proton, and gives us the corresponding alkoxide—or more specifically in this case, a phenoxide. We also get water as a byproduct.

Now, if we think about how favorable this proton transfer is, we can look at the pKa values. The pKa of phenol is about 10, and the pKa of water is around 16. That gives us an equilibrium constant of 1016-10, or about 106, which is very favorable. So we don’t need a stronger base—sodium hydroxide is more than enough to deprotonate the phenol and generate the phenoxide.

Next, when we add the alkyl halide—in this case, allyl bromide—we’re going to see a straightforward SN2 reaction. So I’ll show that SN2 attack like this. As a result, we get a product with a brand-new carbon-carbon bond, formed right here. This is the new bond we just created.

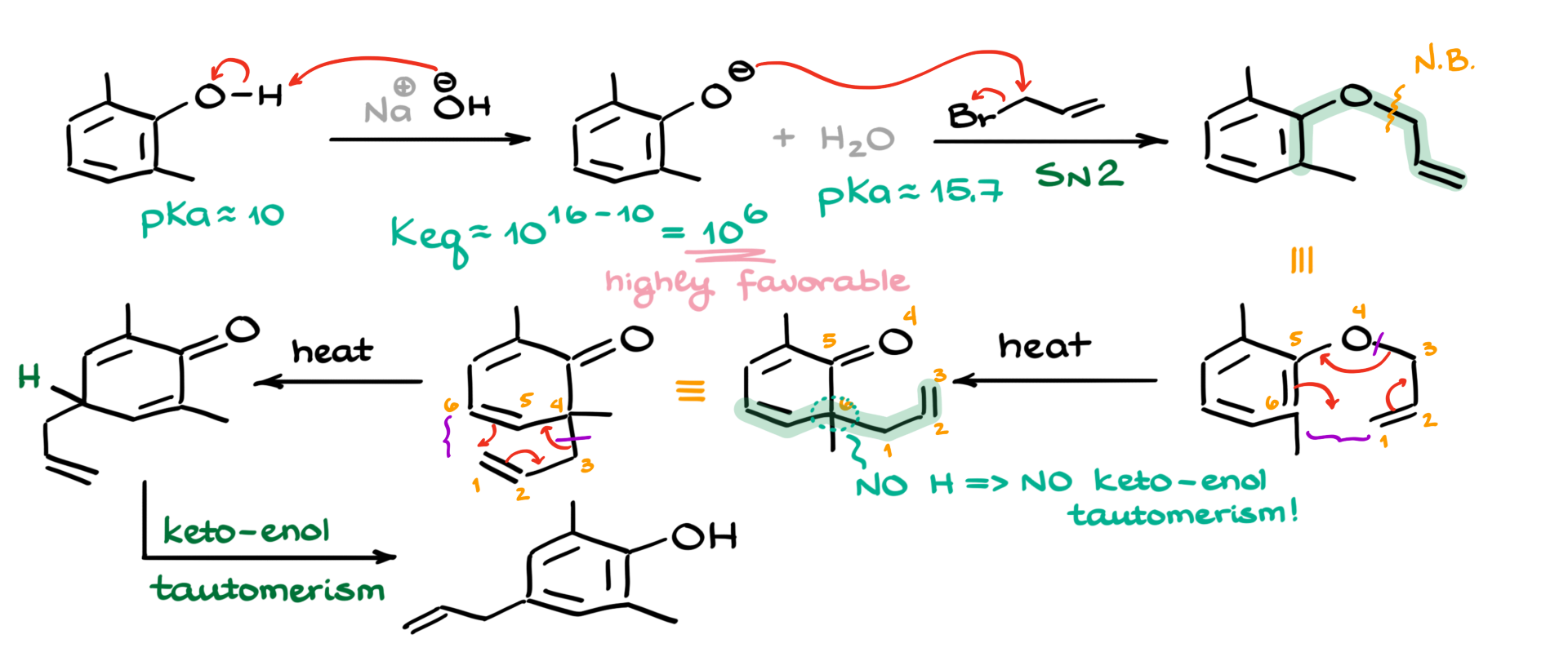

At this point, we can see that this part of the molecule is set up for a Claisen rearrangement. To make things easier, I’ll redraw the molecule and number the atoms: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. During the Claisen rearrangement, the movement of electrons can be shown a few different ways, but I’ll draw it like this. We end up making a new bond between carbons 6 and 1, and we break the bond between the oxygen (atom 4) and carbon 3. So our alkyl group effectively migrates to the nearby atom.

Looking at the rearranged molecule, atoms 1, 2, and 3 are here, with oxygen as atom 4, and then 5 and 6 following. Now, normally after this step, we’d expect a keto-enol tautomerism to regenerate the phenol. However, in this case, we don’t have a hydrogen at the α-position—so no hydrogen, no tautomerism. That means the reaction isn’t stopping here—we’re going to keep going.

Now we’ve got a structure that contains a 1,5-diene system. That opens the door for a Cope rearrangement. Again, I’ll redraw the molecule to make it easier to visualize, and renumber the atoms: 1 through 6. This time, we’ll form a new bond between atoms 1 and 6, and break the bond between 4 and 3. So the electron flow goes like this: this arrow goes here, that one shifts over there, and the last one moves here—giving us the next intermediate.

In this new structure, we do have a hydrogen in the key position, which now allows for the keto-enol tautomerism to occur. I won’t go into the mechanism for that step here, but we can squeeze in the final product right over there.

So as I’ve mentioned before—don’t stop just because you’ve identified one reaction! Always take a moment to see if the molecule can undergo further transformations. In this case, we had a cascade: first the Claisen rearrangement, then the Cope rearrangement, and finally, the keto-enol tautomerism. Pretty cool, right?