Benzyne Chemistry Challenge Mechanism

I have an awesome mechanism for you today, so let’s dive right in and see what we’re working with.

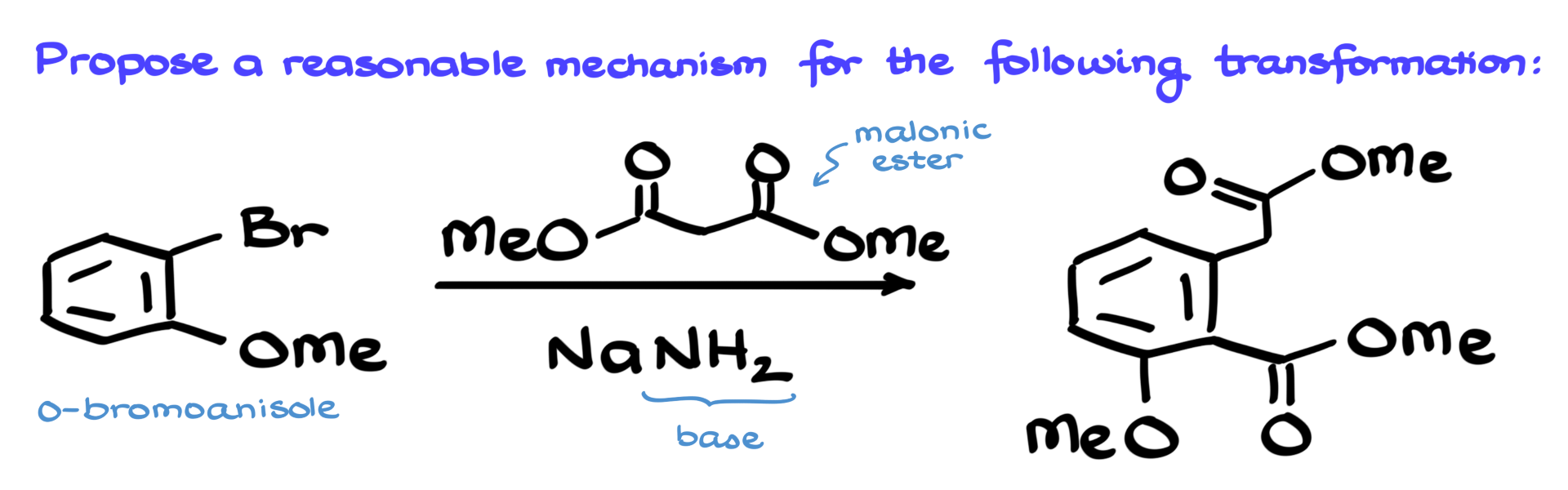

Our starting material here is this o-bromoanisole, and we’re treating it with malonic ester in the presence of sodium amide, which is an incredibly powerful base.

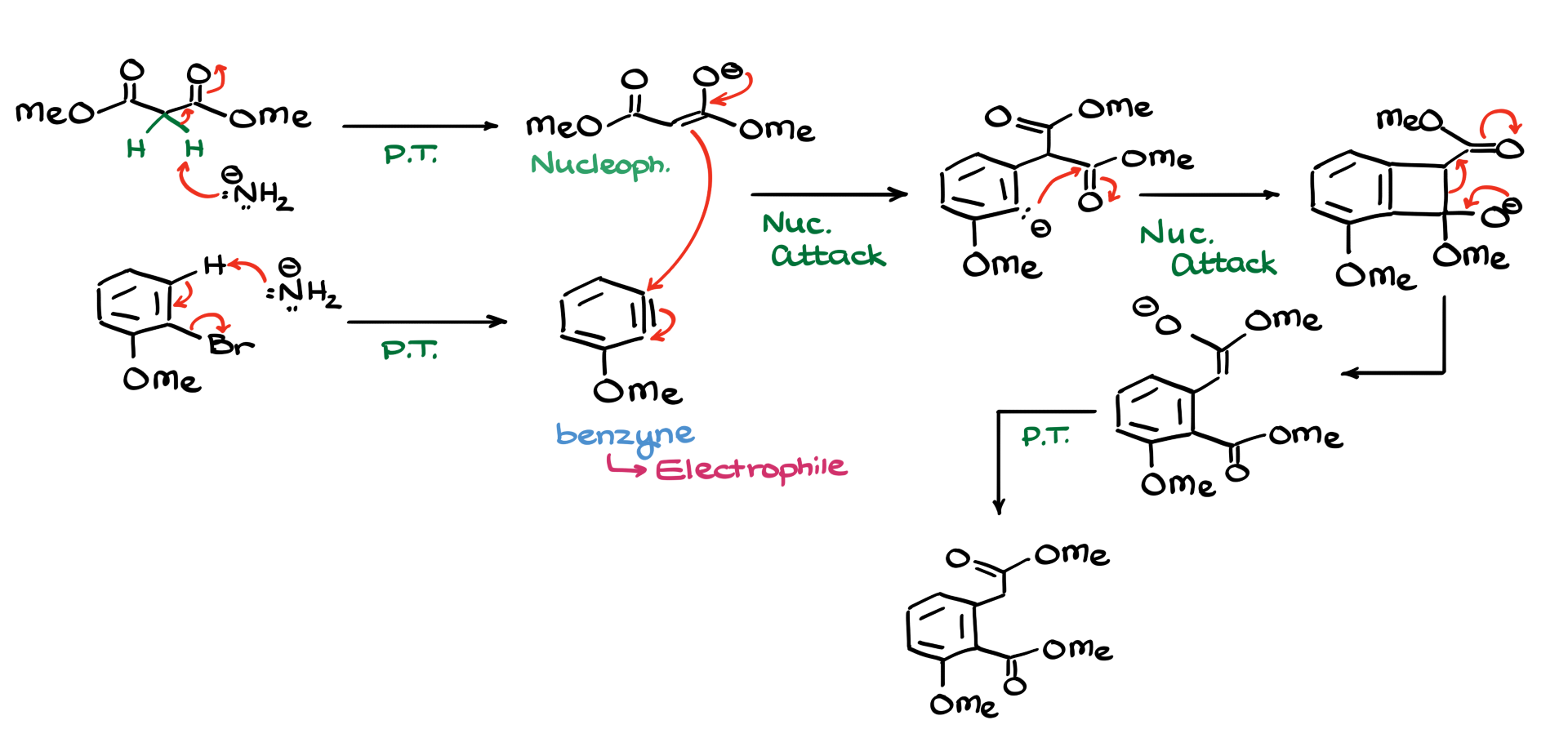

The most straightforward first step would be to take our malonic ester, treat it with sodium amide, deprotonate it, and generate the corresponding enolate. However, the issue here is that while this enolate is a decent nucleophile, we don’t really have anything particularly electrophilic in our system. The bromine on the aromatic ring isn’t a great leaving group, and the ring itself is electron-rich, meaning we can’t even perform a typical nucleophilic aromatic substitution.

But there’s something really cool we can do here. If we take our starting bromide and react it with sodium amide, we can deprotonate it and generate a rather exotic and highly reactive intermediate known as benzyne. Now, the fascinating thing about benzynes is that they are incredibly electrophilic, and conveniently, we already have a nucleophile in our system.

So what happens next? Naturally, the nucleophile is going to attack the electrophile, giving us a negatively charged intermediate. Because of steric hindrance, the nucleophile prefers to attack the carbon of the triple bond that is further away from the methoxide group, since the position right next to the methoxide is a bit too crowded.

At this stage, the negative charge sitting on the carbon of our aromatic ring is extremely unstable. This is an electron-rich system, and that negative charge has nowhere to go—it isn’t stabilized by anything. So what does it do? It reaches for the only electrophile available, which happens to be the carbonyl group. This forms a highly strained four-membered ring intermediate.

Now, four-membered rings are notoriously unstable, and instead of the usual leaving group dissociation that we often see in tetrahedral intermediates, we get something even cooler—a retro-Dieckmann-type reaction that breaks the four-membered ring. This rearrangement leads us to the next intermediate, which, after one final proton transfer, delivers our target molecule.

Isn’t that just crazy? I absolutely love this mechanism!

BTW, this reaction first appeared in the total synthesis paper here: Guyot, M.; Molho, D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1973; 14, 3433.