Acidity of Carboxylic Acids

In this tutorial, I want to talk about the acidity of carboxylic acids and the different factors that influence that acidity.

Aliphatic Carboxylic Acids

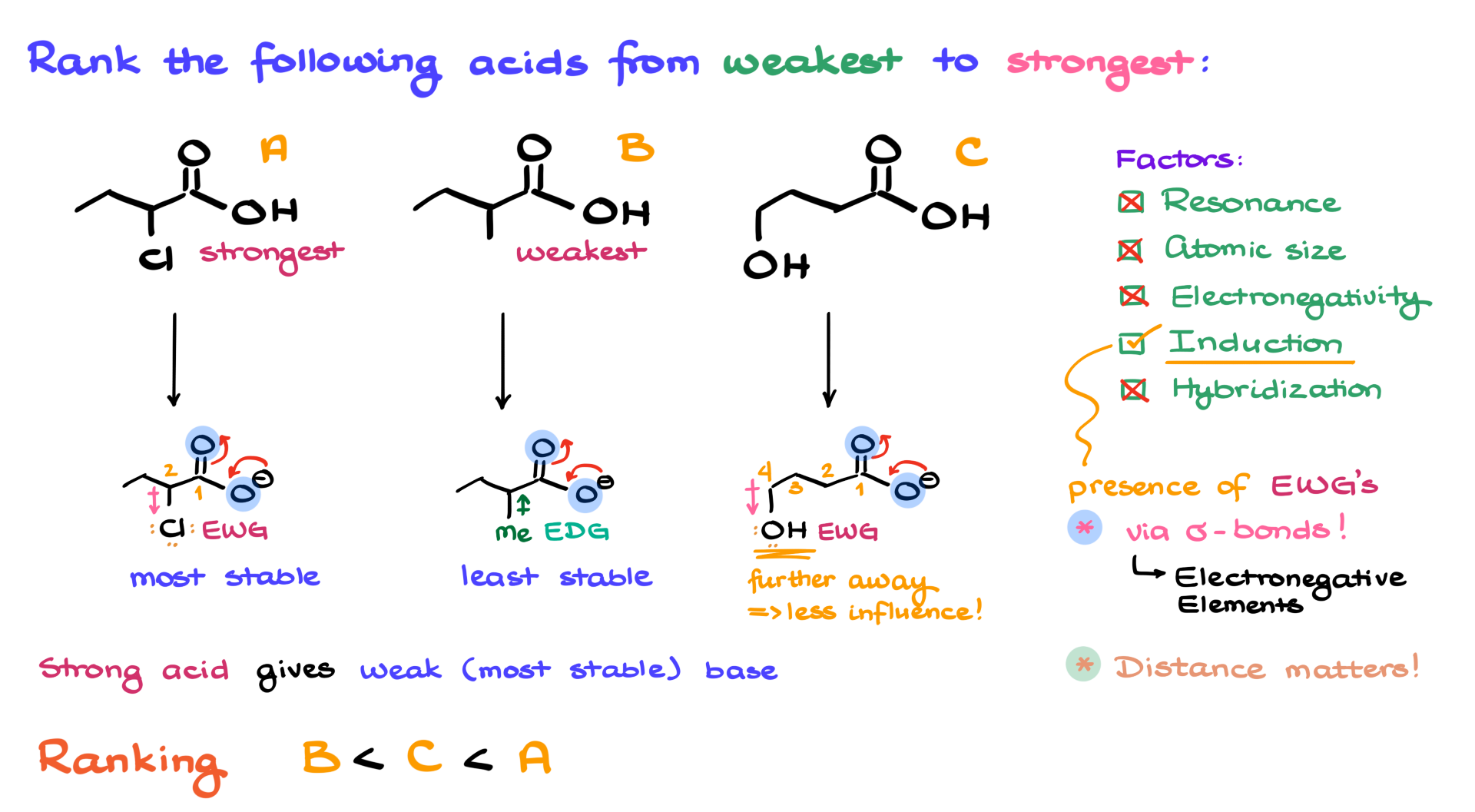

Here’s a fairly common exam question you might encounter on your next test: ranking carboxylic acids based on their strength from weakest to strongest, or vice versa, or even ranking them based on their pKa values. In essence, all of these questions are asking the same thing.

When analyzing the acidity of different molecules, the first thing we typically examine is their conjugate bases and the stability of those conjugate bases. So, let’s start by drawing the conjugate bases of our carboxylic acids and then reminding ourselves of the key factors that determine the stability of negatively charged conjugate bases. These factors include resonance, atomic size of the atom bearing the negative charge, electronegativity of that atom, inductive effects present in the molecule, and the hybridization of the atom with the negative charge.

Looking at these factors from top to bottom, I can see that in terms of resonance, all my carboxylic acids have the same resonance stabilization, so there’s no difference there. Additionally, the negative charge is always on oxygen, so there’s no variation in atomic size, electronegativity, or hybridization in this case either. That leaves us with the inductive effect.

What is Induction?

Now, what exactly is induction? Simply put, induction is the influence of electron-withdrawing groups, which pull electron density toward themselves via sigma bonds. In my example, on the left, I have chlorine, which pulls electron density toward itself. On the right, I have an OH group, which also pulls electron density. However, in the middle, I have a methyl group (Me), which pushes electron density into the molecule rather than pulling it away. Therefore, we classify both chlorine and OH as electron-withdrawing groups, while the methyl group is an electron-donating group.

Since we are focusing purely on inductive effects here, the fact that both chlorine and oxygen have lone pairs is irrelevant. They cannot use those lone pairs to push electron density into the molecule because there is no resonance involving these groups. The only thing that matters is their electronegativity, which allows them to pull electron density toward themselves. However, another crucial factor is distance: the closer the electron-withdrawing group is to the negatively charged region, the stronger its inductive effect.

Looking at my two molecules with electron-withdrawing groups, the chlorine is on the second carbon relative to the carboxylate group, whereas the oxygen in the OH group is on the fourth atom away. That distance is significant—every additional bond that pushes an electron-withdrawing group further from the negatively charged site reduces its influence. The further away the group, the less effective it is at stabilizing the negative charge via induction.

Based on this, I can conclude that the molecule with chlorine will have the most stable conjugate base, while the one with the methyl group will have the least stable conjugate base. The electron-donating methyl group actually destabilizes the conjugate base because it pushes electron density toward the negatively charged carboxylate, which already has a negative charge and does not want more electron density.

Now, remember the key principle of acid-base chemistry: strong acids produce weak (or stable) conjugate bases, while weak acids produce strong (or unstable) conjugate bases. This means that the most stable conjugate base corresponds to the strongest acid, while the least stable conjugate base corresponds to the weakest acid. So, our ranking goes as follows: molecule B is the weakest carboxylic acid, followed by molecule C, and finally, molecule A is the strongest acid. Easy enough, right?

Aromatic Carboxylic Acids

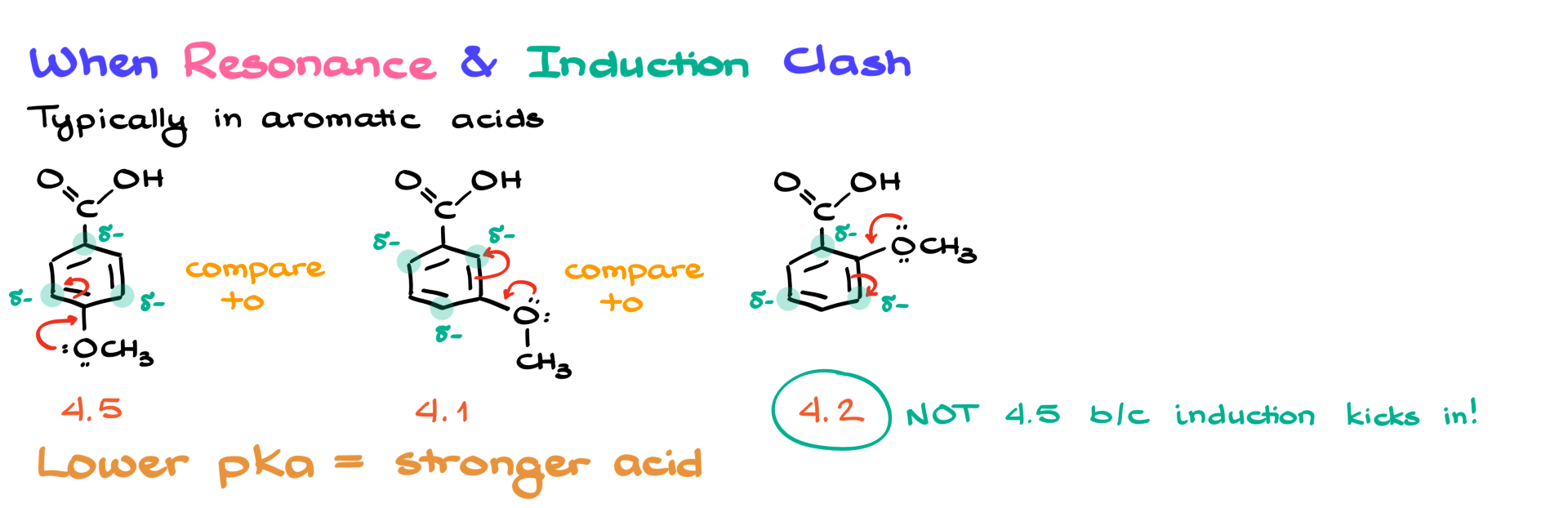

Now, things get a little trickier when resonance and inductive effects clash with each other. Let me explain. This is often seen in aromatic carboxylic acids, so let’s examine these three molecules.

To compare their acidity, I could look at their pKa values. A lower pKa value means a stronger acid. My first acid has a pKa of about 4.5. The second one has a pKa of roughly 4.1, which makes sense because the oxygen, an electron-withdrawing group, is closer to the carboxylic acid, meaning it has a stronger inductive effect. However, the third acid presents an interesting situation. Here, the electron-withdrawing group is even closer to the carboxylic acid, but its effect appears weaker, which seems counterintuitive—until we consider resonance.

The lone pairs on the oxygen of the OCH3 group become relevant here because they can participate in resonance within the aromatic ring, altering the electron density distribution. In the first case, if I examine the different resonance structures, I find that certain positions in the ring develop increased electron density, leading to a partial negative charge. This means that instead of stabilizing the carboxylic acid, this group is actually generating a partial negative charge right next to it, reducing its acidity.

In the second case, where the electron-withdrawing oxygen is positioned further away, the resonance structures place the negative charge in positions that do not directly interfere with the carboxylic acid. As a result, the inductive effect is still felt, making the acid stronger. However, in the third case, even though the OCH3 group is closer to the carboxylate, the resonance effect is now directly influencing the carboxylic acid behavior. Because the resonance is pushing electron density toward the same positions as in the first molecule, the pKa does not drop as much as expected. However, due to its proximity, the OCH3 group still exhibits a stronger inductive effect than in the first example, so the acidity is not as weak as in that case, but also not as strong as in the second example.

[Note: I got curious and I’ve checked a few different sources for the pKa values for methoxybenzoic acid, and looks like there are values 4.08 and 4.2 for 2-methoxybenzoic acid. It does appear that the pKa value is heavily dependent of the temperature, concentration, and how exactly it was measure. So, perhaps, it was not the best set of molecules to illustrate what I was saying there, but nonetheless, this is the idea that your instructor would expect from you on the test. Most of the time, instructors don’t double-check the actual experimental pKa values and go with the “typical” example the way I described it.]

So, when dealing with regular carboxylic acids, we focus purely on inductive effects. However, in the case of aromatic carboxylic acids, we must consider both inductive and resonance effects simultaneously. Keep in mind that resonance effects are typically more powerful than inductive effects, so they must always be taken into account. And that’s all you need to know to rank carboxylic acids based on acidity!