28. Synthesis of a Dicarbonyl

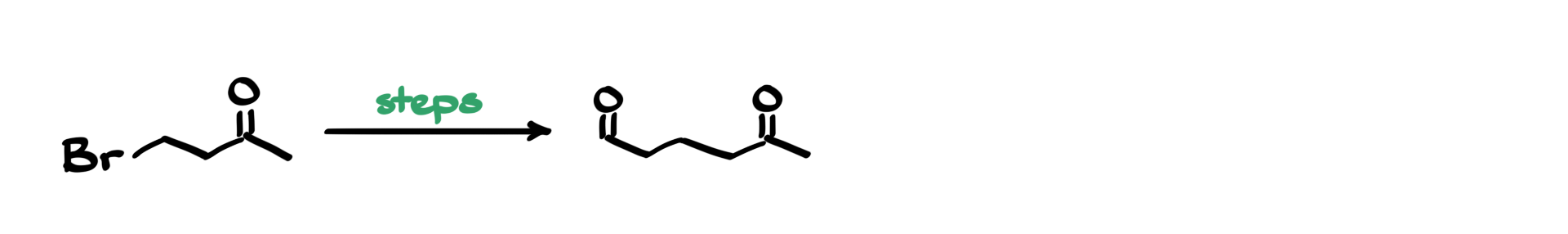

I have a fun synthesis for you today, where we are starting with this β-bromoketone and aiming to synthesize this dicarbonyl compound as our target molecule.

As always, I begin by analyzing both the starting material and the product, focusing on the functional groups.

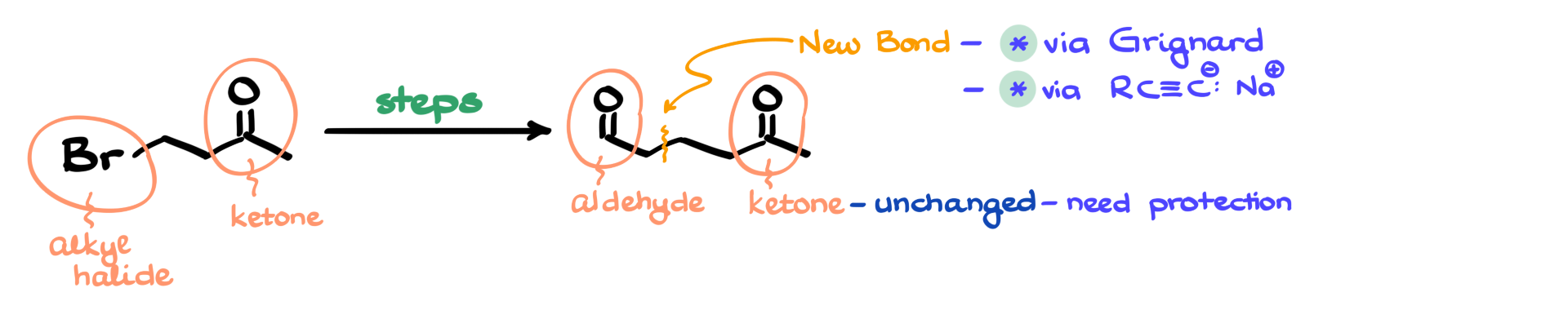

In my starting material, I have an alkyl halide and a ketone. In my final product, I still have a ketone, but I also now have an aldehyde. One key observation I make right away is that the ketone remains unchanged throughout the synthesis. Additionally, by carefully tracking my carbon atoms, I see that I need to form a new carbon-carbon bond.

Now, when it comes to carbon-carbon bond formation, our two main synthetic strategies typically involve either a Grignard reagent or an alkyne-derived nucleophile (such as an acetylide anion). In both cases, the ketone must be protected; otherwise, it would undergo an unwanted reaction with the nucleophile. This means that no matter which approach I take, the first step of my synthesis must be the protection of the carbonyl group.

For this, I will use a classic method: acetal formation. I treat my starting material with ethylene glycol in the presence of p-toluenesulfonic acid as a catalyst, forming the corresponding acetal. Now, with the ketone safely protected, I can proceed with my carbon-carbon bond-forming strategy.

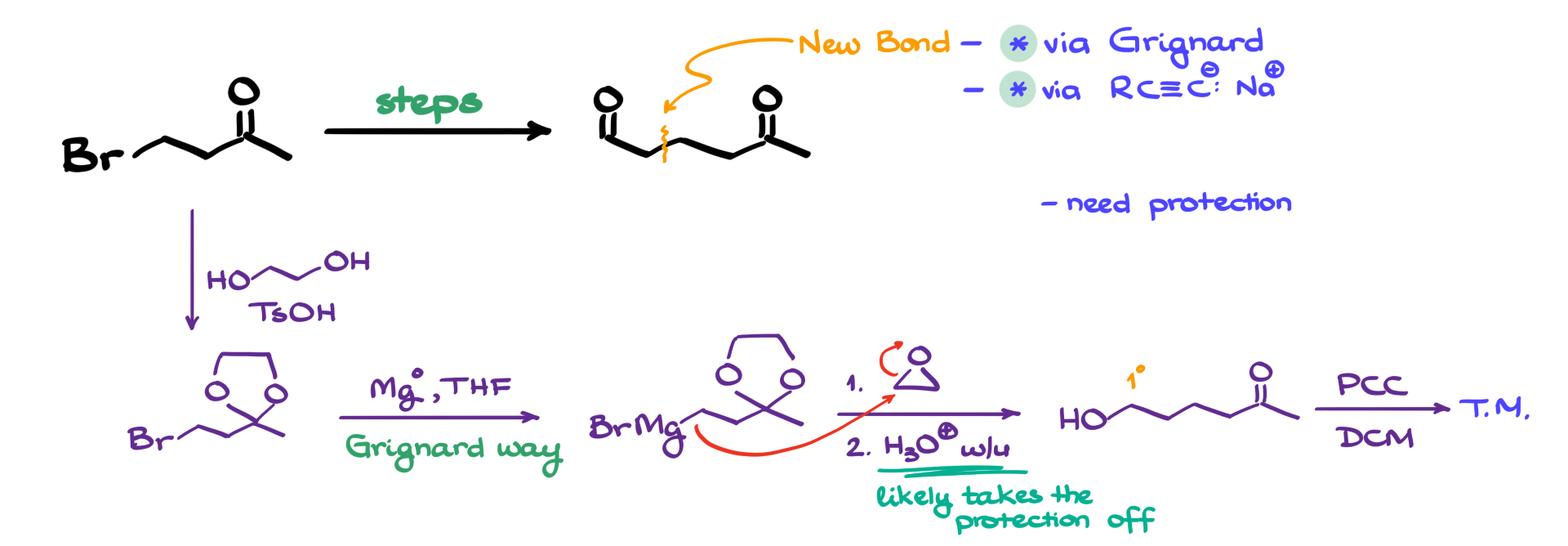

Grignard Pathway

If I go the Grignard route, my next step is to convert the alkyl halide into a Grignard reagent. This is done by treating the molecule with magnesium in THF or dry ether. Once I have my Grignard reagent, I will react it with an epoxide.

The key insight here is that my target molecule has two additional carbon atoms, and there is a functional group on the second carbon from the site of attachment. This strongly suggests an epoxide-opening reaction. So, my Grignard reagent attacks the less substituted carbon of an epoxide, opening the ring. After an acidic workup, we obtain the corresponding alcohol.

Interestingly, during the acidic workup, my protecting group also falls off. Depending on the conditions used, we can remove the acetal protection at this stage, eliminating the need for a separate deprotection step later.

The only remaining transformation is the oxidation of the newly formed primary alcohol into an aldehyde. This can be achieved using PCC, PDC, Swern oxidation, or Dess-Martin periodinane—any of these will work, as long as they stop at the aldehyde stage rather than proceeding to the carboxylic acid. This final oxidation step gives us our target molecule.

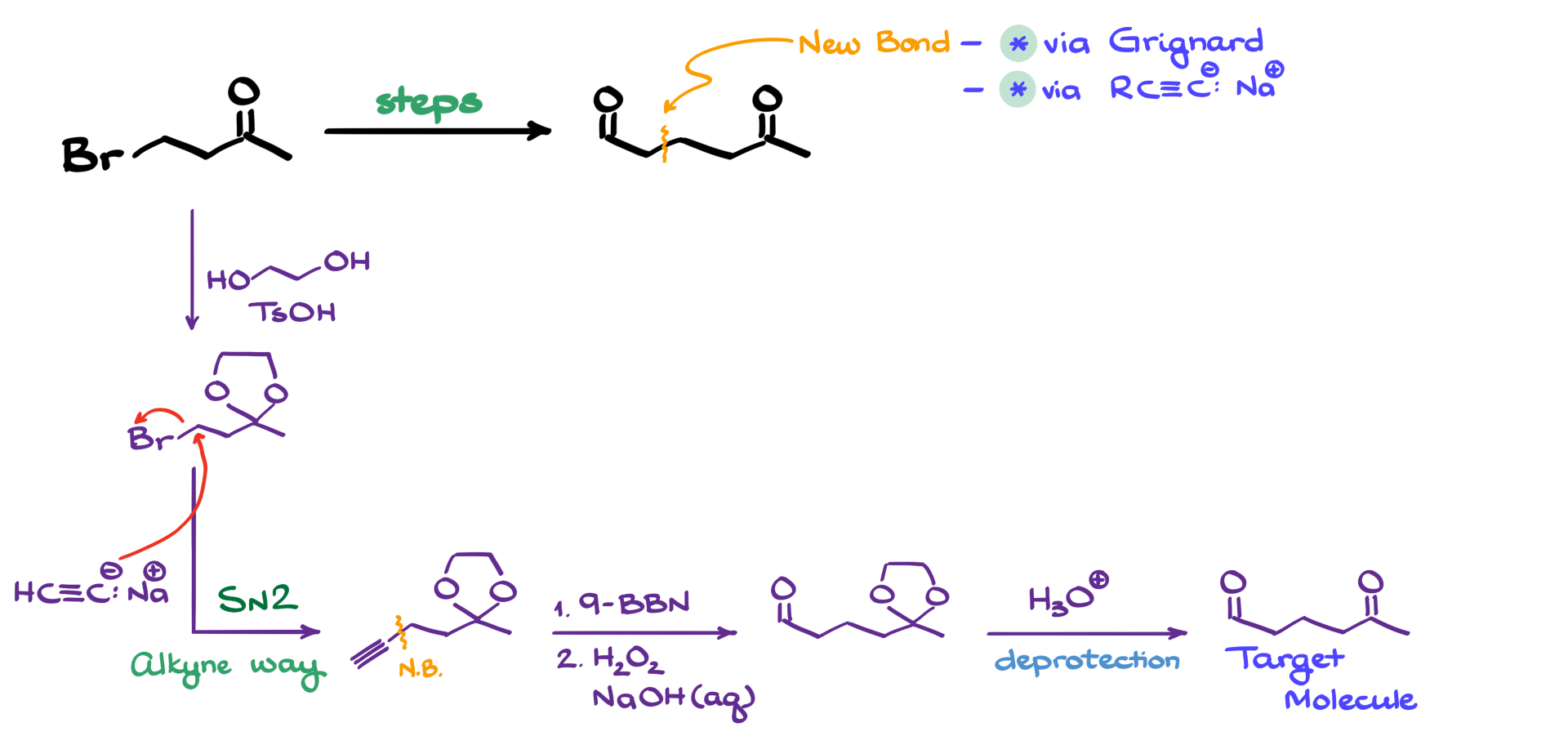

Alkyne Pathway

Alternatively, we could use an alkyne-derived nucleophile to extend the carbon chain. In this case, we introduce the two new carbons by performing an SN2 reaction using an acetylide ion. The alkyne nucleophile attacks the β-bromo-ketone, displacing bromide in a straightforward SN2 reaction. This results in a two-carbon extension, where our newly formed carbon-carbon bond is now in place.

From here, we need to convert the terminal alkyne into the corresponding aldehyde. This can be done using hydroboration-oxidation. For the boron-containing reagent, I choose 9-BBN, followed by oxidation with hydrogen peroxide in a basic medium. After going through the mechanistic steps, including keto-enol tautomerization, we obtain the aldehyde.

The last step is to remove the protecting group by performing acetal hydrolysis, which regenerates the ketone, giving us the final target molecule.

Comparing the Two Pathways

In both the Grignard and alkyne-based approaches, the synthesis requires four steps:

1. Protecting the ketone (acetal formation)

2. Carbon-carbon bond formation (Grignard addition to an epoxide or SN2 reaction with an acetylide ion)

3. Functional group transformation (oxidation of alcohol to aldehyde or hydroboration-oxidation of an alkyne)

4. Deprotection (acetal hydrolysis)

So, which pathway do you like better? Let me know in the comments!