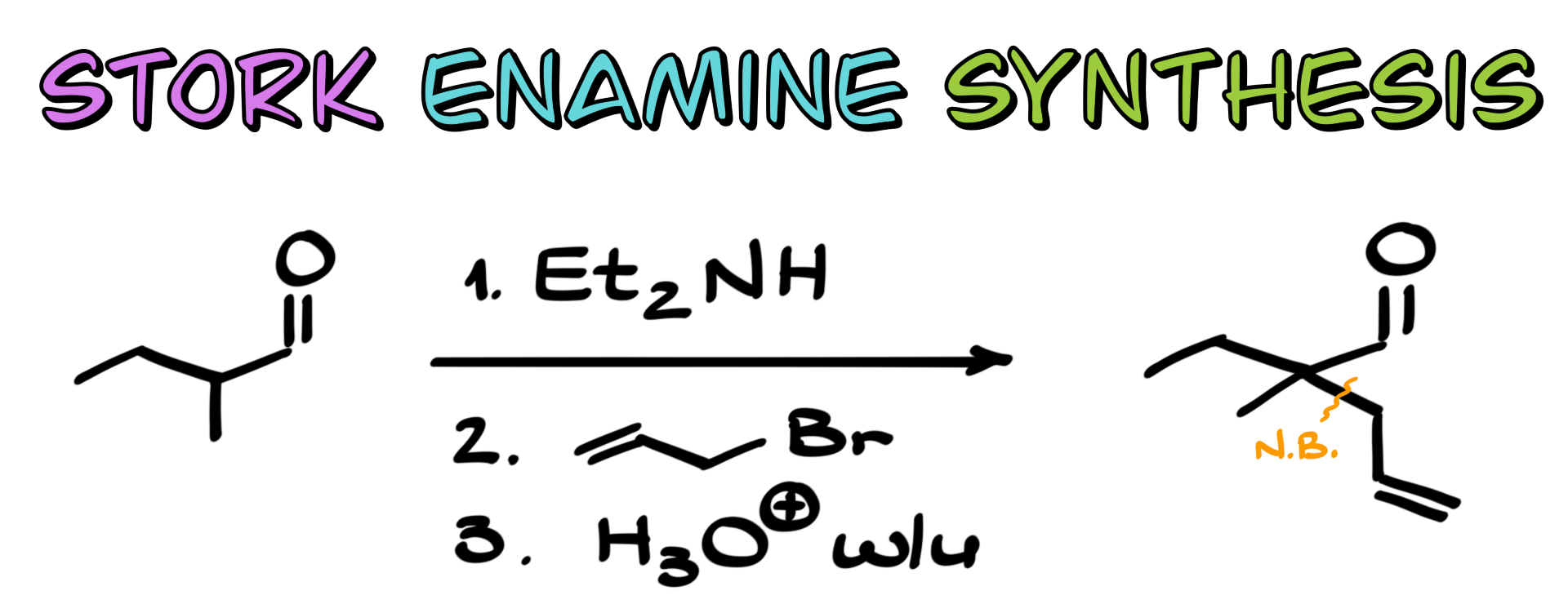

Stork Enamine Synthesis

In this tutorial, I want to talk about the Stork enamine synthesis, which is a useful workaround when classic enol or enolate chemistry may not be a viable option.

General Scheme of the Stork Enamine Synthesis

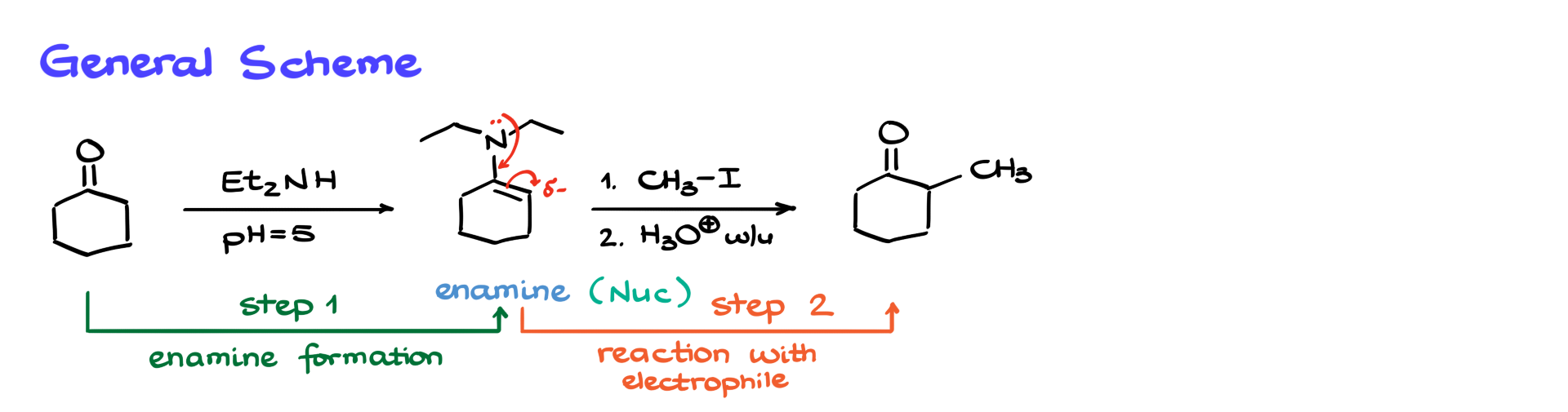

So first of all, what exactly is the Stork enamine synthesis? Well, we start by taking a carbonyl compound, typically an aldehyde or a ketone, and converting it into the corresponding enamine. I have a dedicated tutorial on enamine formation, so if you need a refresher, you can check it out.

Now, coming back to our enamine, there’s something really cool about this species. Enamines are inherently nucleophilic. Because the electron pair on the nitrogen can participate in resonance with the double bond, there is a significant δ⁻ on the carbon, making that carbon relatively nucleophilic. This means that if it reacts with an electrophile, we can potentially create a new carbon-carbon bond. And we know that one of the huge goals of organic synthesis is carbon-carbon bond formation, along with functional group transformations and other key reactions.

Why Bother with Stork Enamine Synthesis?

You might be wondering why we bother with enamine synthesis if we can seemingly accomplish all of this with simple enol or enolate chemistry. Well, there are a few reasons.

- From a synthetic perspective, enamines are stable species, so we can prepare them beforehand and store them for future use. This is especially useful if you frequently use the same starting materials. But that’s a minor advantage.

- A bigger reason, especially when it comes to aldehydes, is that aldehydes are difficult to enolize under basic conditions. Instead of attempting to enolize an aldehyde, which is nearly impossible, we can convert it into a nucleophilic species by forming the corresponding enamine.

- Similarly, under acidic conditions, aldehydes are extremely electrophilic, making their reactions difficult to control. Using enamines allows us to direct the reaction in the way we want.

Alkylation via Stork Enamine

Let’s go through an example to see how this works.

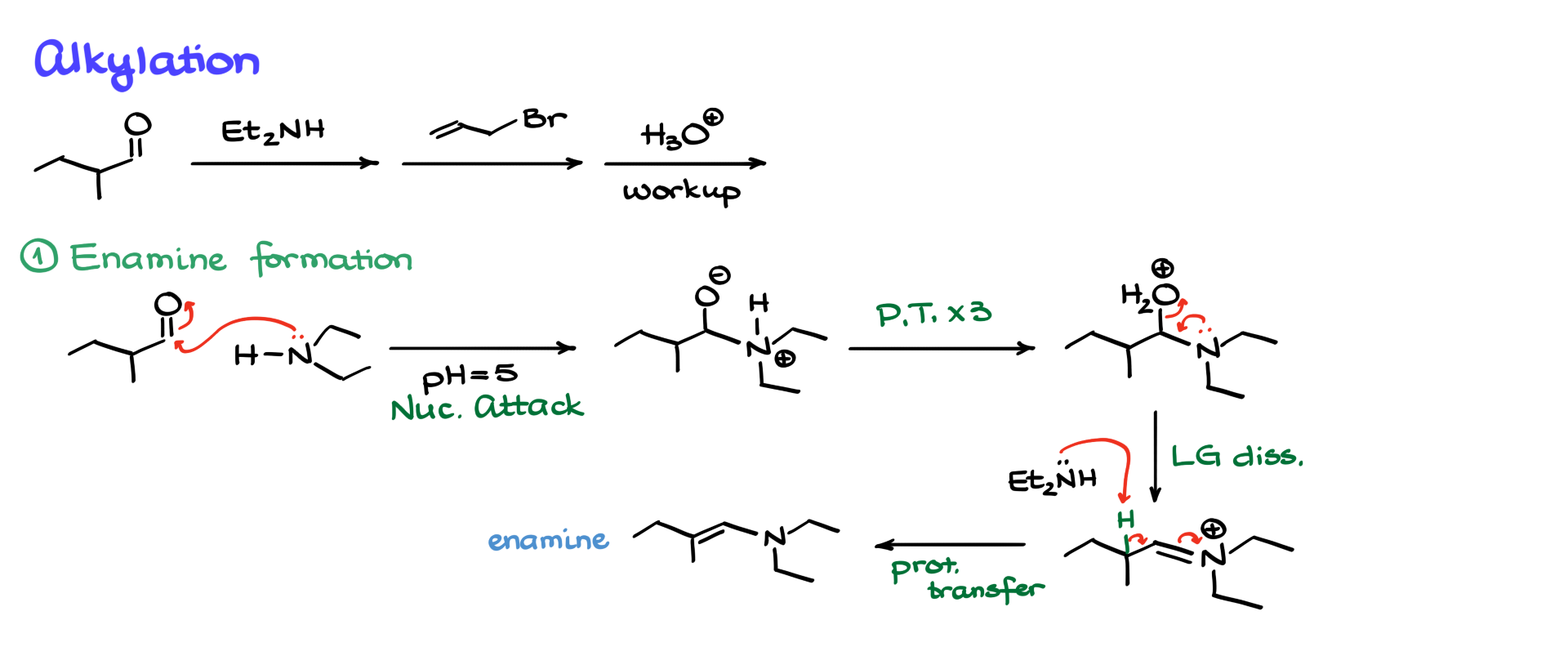

First, we form the enamine. We start by having the nitrogen attack the carbonyl, generating an intermediate. From this point, we undergo several proton transfers—three, to be exact—leading to another intermediate. At this stage, water acts as a leaving group, assisted by the nitrogen, forming an iminium intermediate. This iminium intermediate isn’t particularly stable, so we bring in another equivalent of diethylamine, which deprotonates at the appropriate position, finally giving us the enamine.

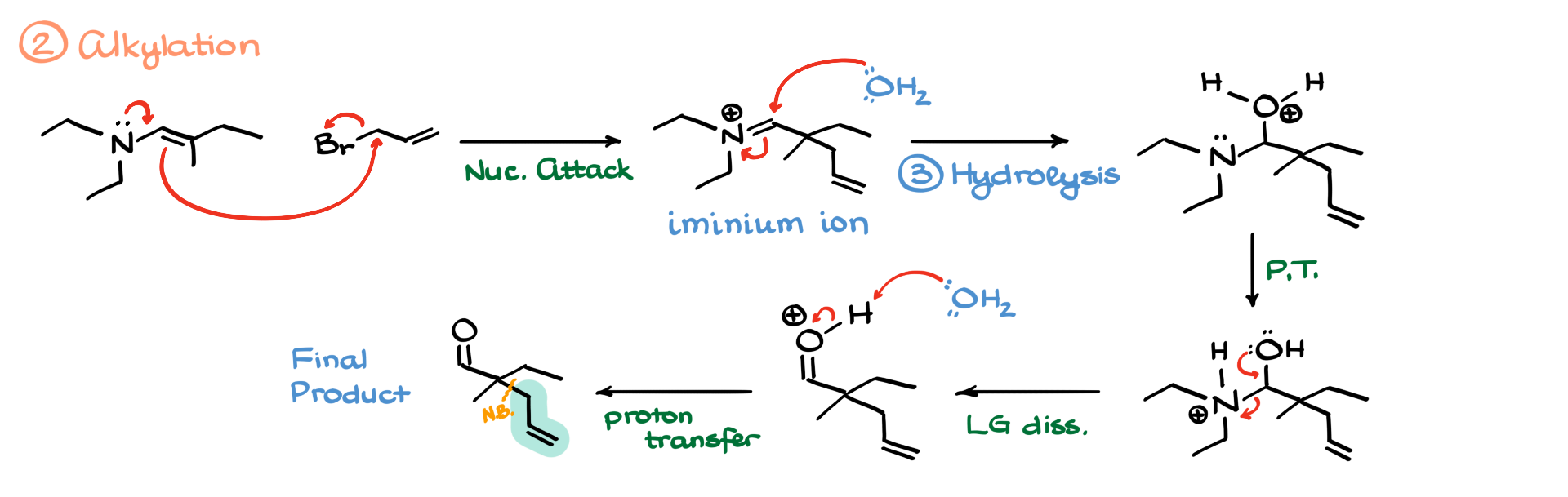

I know I went through this mechanism quickly, but as I mentioned earlier, I have a dedicated tutorial on this mechanism. Now, once we have our enamine, we recall that enamines are good nucleophiles. Next, we proceed with the alkylation reaction. We take our enamine and an alkyl halide, and the nucleophilic carbon in the enamine attacks the electrophilic alkyl halide, kicking out the leaving group. As a result, we form a new carbon-carbon bond, generating an iminium ion.

From here, we move on to hydrolysis. Water attacks the iminium ion, leading to an intermediate, which undergoes further proton transfers, ultimately converting the nitrogen-containing moiety into a leaving group. The oxygen’s electrons help push off the nitrogen, forming a protonated aldehyde. A final deprotonation step then gives us our final product, where we can clearly see the new bond that has been formed.

If you were to attempt this reaction under basic conditions via simple enolization, you’d have a hard time. Aldehydes are so electrophilic that even if you use something completely non-nucleophilic like LDA, the aldehyde would still undergo nucleophilic attack at the carbonyl rather than enolization. While enolizing aldehydes isn’t impossible, it’s extremely difficult. The Stork enamine synthesis provides an excellent workaround.

Aldol Formation via Stork Enamine

Now, let’s look at another example.

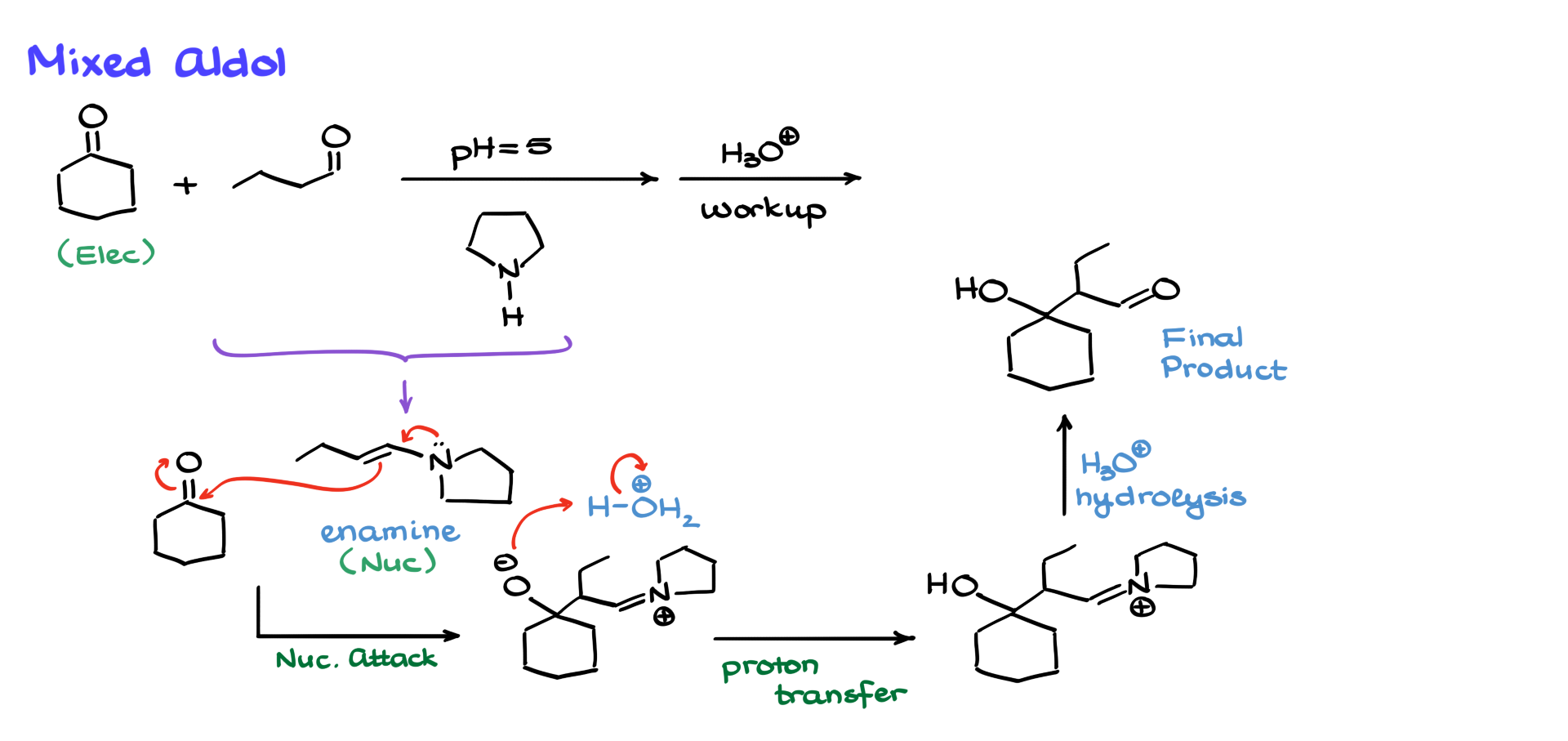

Suppose we want to perform a mixed aldol reaction. In a typical case, the aldehyde would act as the electrophile, while the ketone would enolize and serve as the nucleophile. But what if we wanted the aldehyde to be the nucleophile instead? Without any tricks, we’d be out of luck. However, if we use the Stork enamine synthesis—first converting the aldehyde into an enamine by adding a secondary amine and then performing an acidic workup—we can achieve our goal. Since aldehydes are more electrophilic than ketones, the aldehyde reacts with the amine first, forming an enamine. This enamine now serves as the nucleophile, attacking the ketone’s carbonyl group. After a series of steps, including hydrolysis, we obtain our final product.

While the Stork enamine synthesis may not be the best alternative for mixed aldol reactions—it generally doesn’t give great yields—it’s still better to have some yield than none. And this reaction has been reported in the literature, so with careful execution, it is possible to achieve.

Scope of the Stork Enamine Synthesis

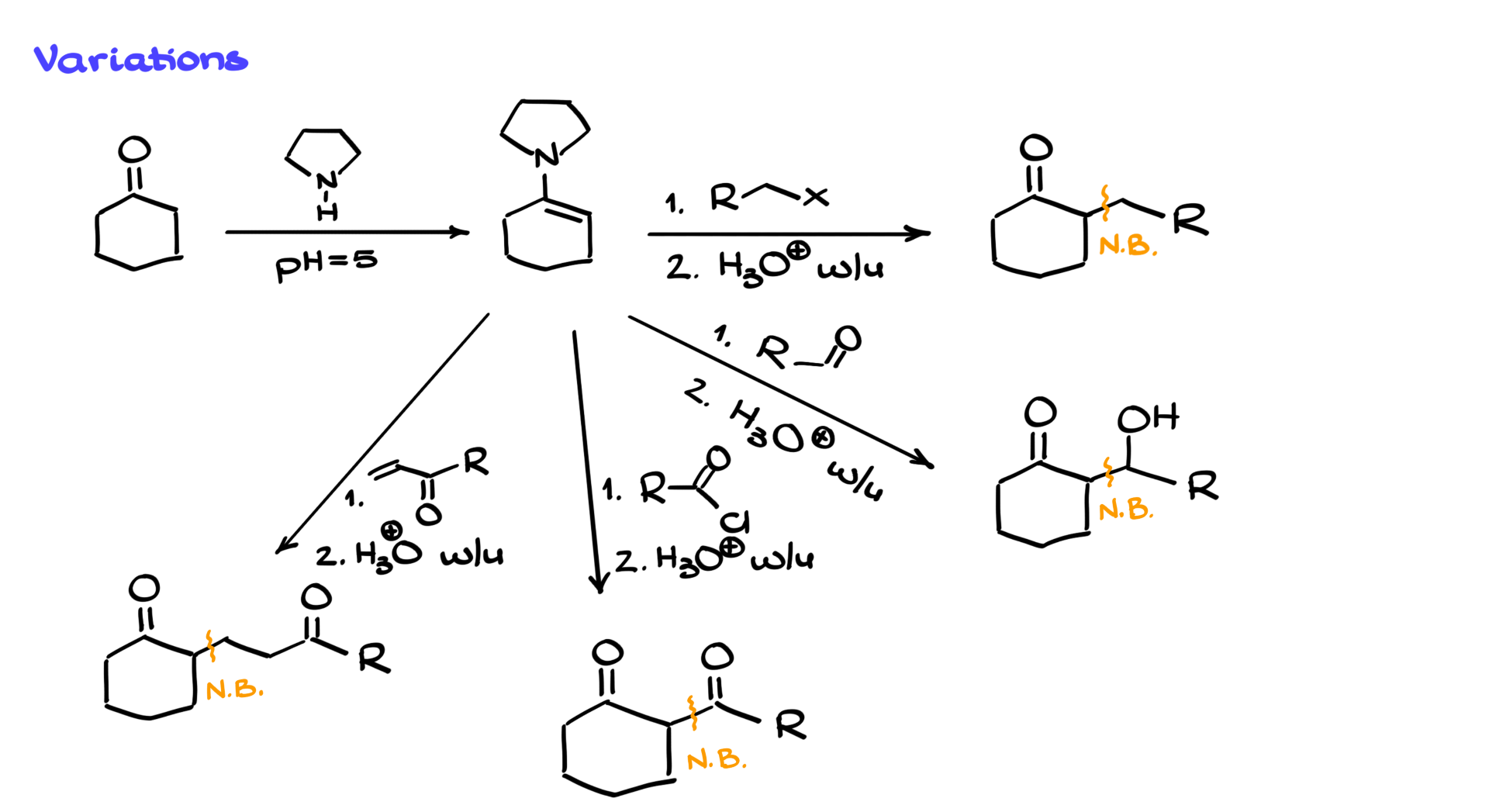

But these are just the beginning. There are many variations of the Stork enamine synthesis.

For example, starting with cyclohexanone, we can convert it into an enamine and then perform alkylation to add a group at the α-position. We can react it with an aldehyde or ketone to form an aldol product, which can then undergo elimination to form an α,β-unsaturated compound. We can also use it in a Claisen-like reaction with acid halides, generating a 1,3-dicarbonyl. Where this method truly shines is in Michael addition reactions. Regular enolates, unless stabilized by two carbonyls, are not very effective Michael donors. However, enamines are excellent Michael donors. This makes the Stork enamine synthesis a great approach for achieving Michael additions with simple carbonyl compounds, yielding good results.

And even that doesn’t cover the full scope of the Stork enamine synthesis. This method is incredibly powerful, and while the examples I’ve shown you are important to remember for your course, there are many other cases where this approach excels.

So, what do you think about the Stork enamine synthesis? Have you encountered this sequence before? Let me know in the comments below!