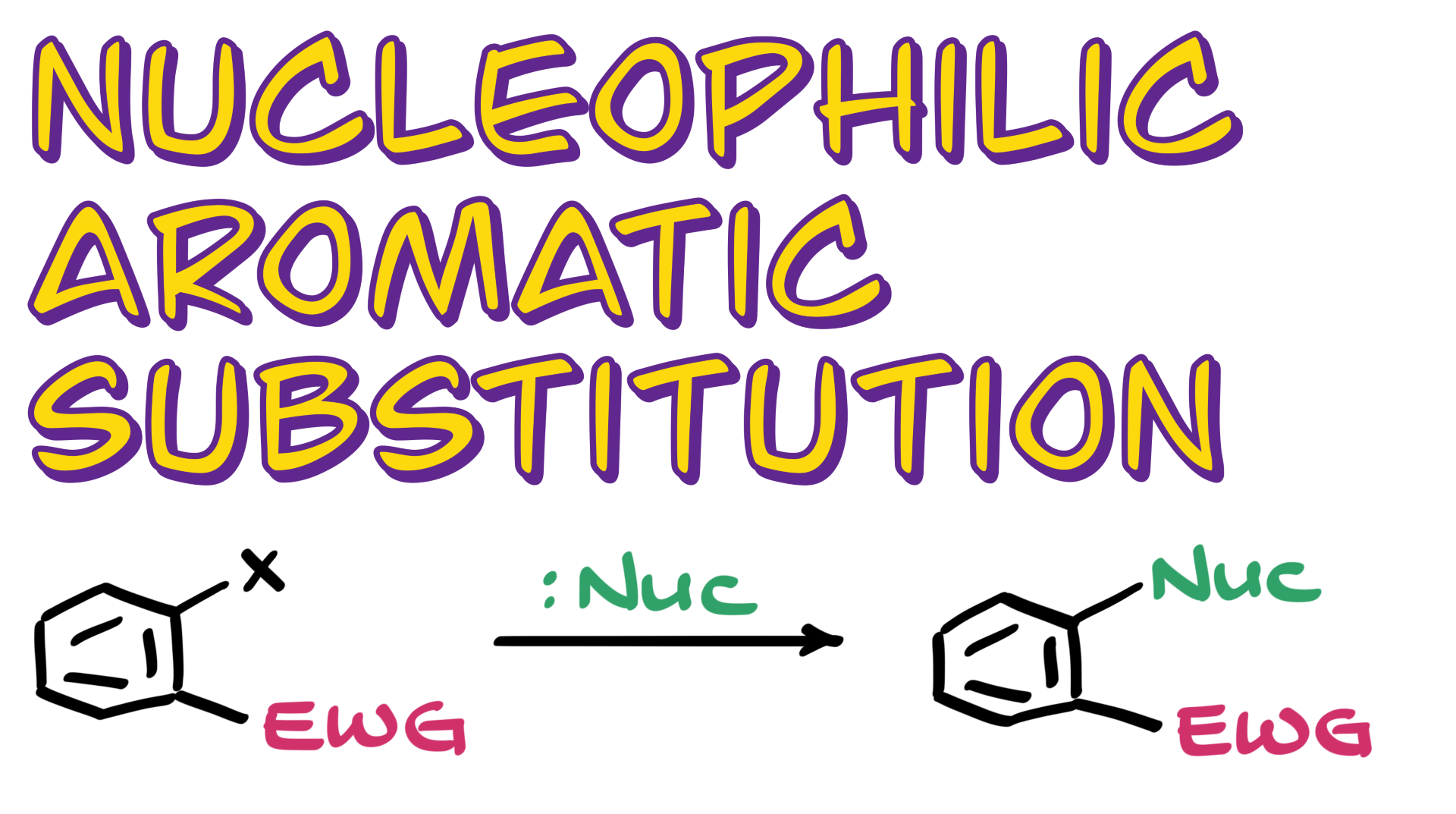

Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution

In this tutorial, I want to talk about nucleophilic aromatic substitution reactions.

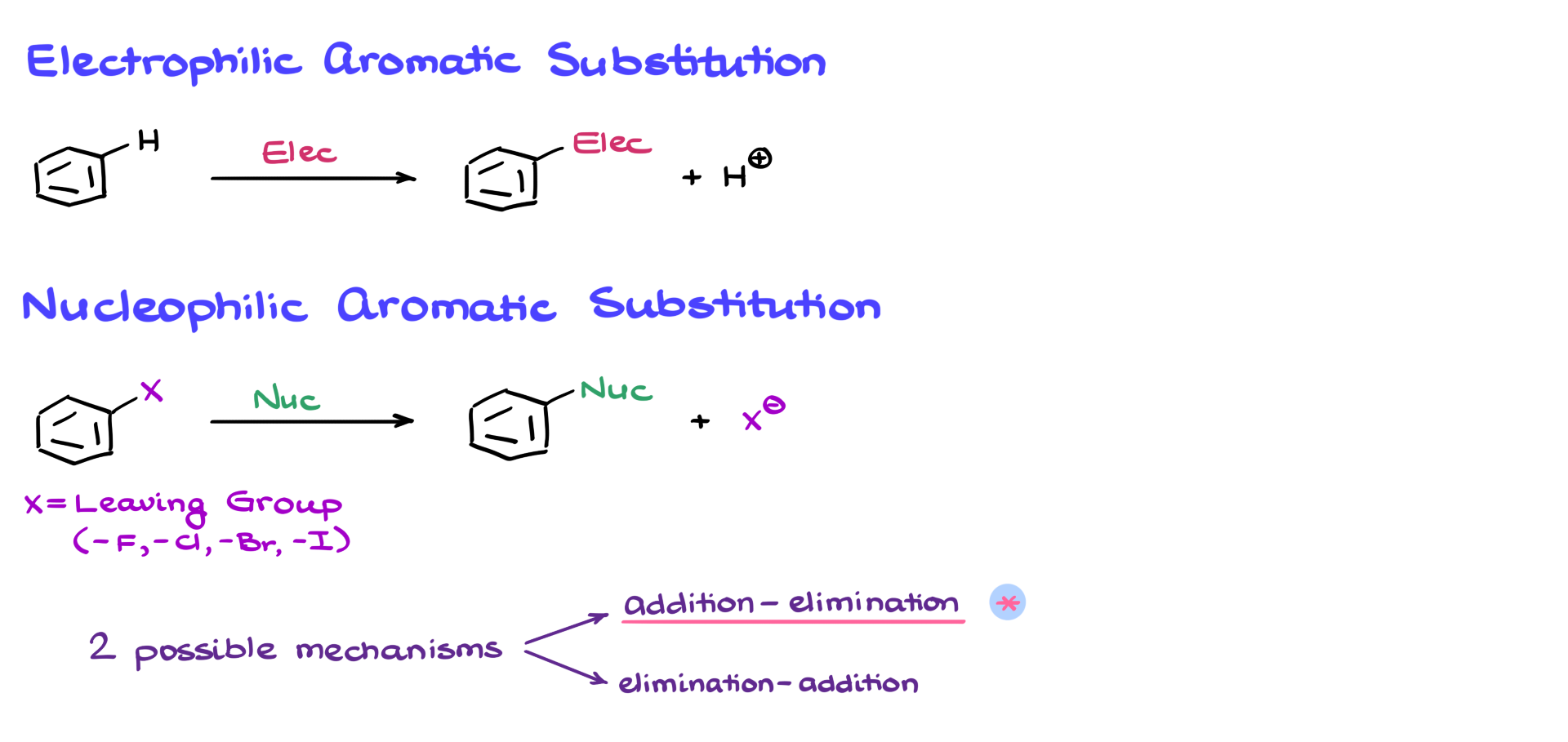

When it comes to electrophilic aromatic substitution, we replace a hydrogen in the molecule with some sort of electrophile. In contrast, nucleophilic aromatic substitution requires an aromatic molecule with a leaving group, which is typically a halide like fluorine, chlorine, bromine, or iodine. And yes, we will be using fluorine as a leaving group, but we’ll discuss that in more detail later.

In this type of reaction, we take the molecule and treat it with a nucleophile, which results in replacing the leaving group with the nucleophile. To make things even more interesting, there are two possible mechanisms for nucleophilic aromatic substitution: addition-elimination and elimination-addition. Not the most creative names, I know. In this tutorial, we will focus on the addition-elimination mechanism, which is the main mechanism you’ll encounter in your course, though we will briefly touch on the other one as well.

Mechanism of the Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution

Let’s go through the mechanism of nucleophilic aromatic substitution.

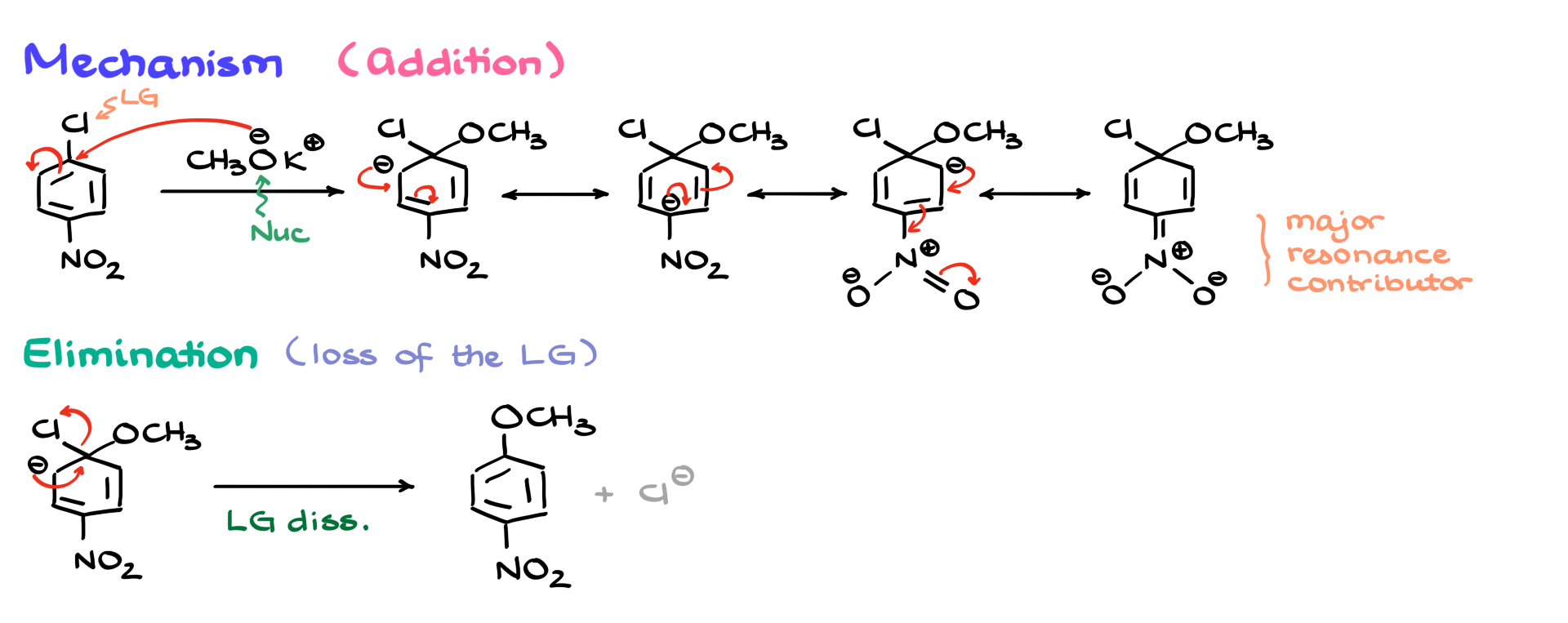

I’m starting with an aromatic compound that has a nitro group and a chlorine positioned para to each other. I will treat this molecule with potassium methoxide. From my preliminary analysis, I can see that chlorine is the typical leaving group here, so it will likely be replaced. The methoxide serves as the nucleophile.

The reaction begins with the nucleophile attacking the carbon where the chlorine is attached, generating a negatively charged intermediate. Similar to electrophilic aromatic substitution, resonance plays a crucial role here. I can draw multiple resonance structures by moving electrons around the ring, leading to different intermediates. Importantly, the nitro group is not just a random collection of atoms—it plays a key role in stabilizing the negative charge through resonance. The structure where the negative charge is on the oxygen of the nitro group is a major resonance contributor and is particularly important for the overall mechanism.

This completes the “addition” step of the addition-elimination mechanism. Now we move on to the “elimination” step, where we lose the leaving group. At this point, the electrons shift back, expelling chlorine from the molecule, leaving us with the final product and Cl⁻ floating around, which we no longer care about.

Role of the Electron-Withdrawing Group

While this mechanism might seem simple, there are a few crucial points to keep in mind.

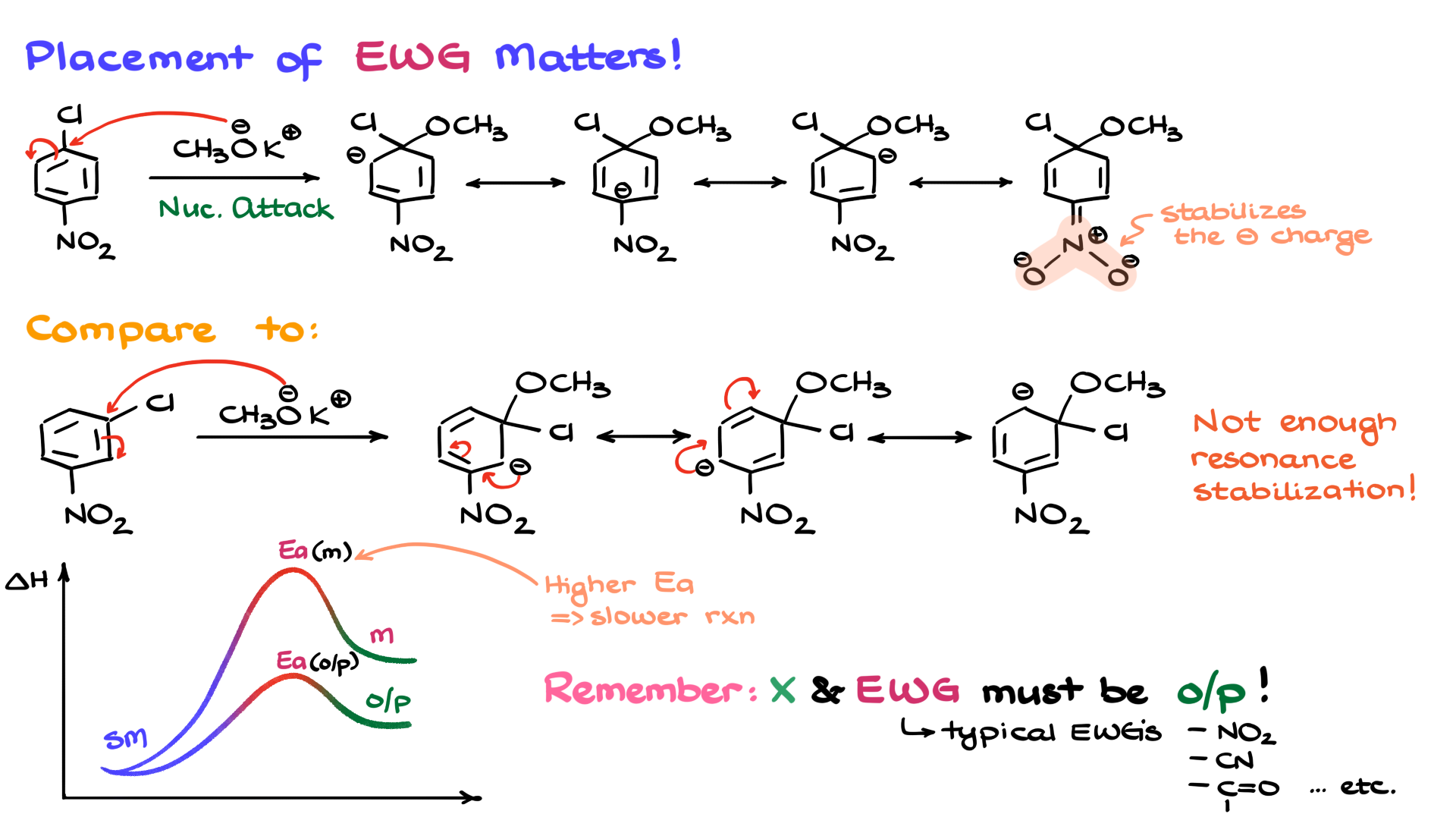

First, the electron-withdrawing group is absolutely essential. Its position matters significantly. Let’s consider what happens if the nitro group is in the wrong position. If the nitro group is not properly positioned to stabilize the negative charge, the reaction becomes much less favorable. To illustrate this, I’ll compare the initial reaction with another scenario where the nitro group is meta instead of para. In this case, methoxide can still attack the position where the leaving group is located, and resonance structures can still form, but they are not sufficient to stabilize the negative charge effectively. Without the nitro group’s stabilization, the reaction becomes significantly slower—perhaps not impossible, but impractically slow.

From a kinetic perspective, I can illustrate this with a reaction diagram showing activation energy. The activation energy for the meta-position reaction is much higher than for the ortho-para reaction because the intermediate is not well stabilized. This means that the reaction at the meta position is much slower. So, the key takeaway here is that the electron-withdrawing group and the leaving group must be ortho or para to each other.

A quick reminder: typical electron-withdrawing groups include nitro (-NO₂), nitriles (-CN), carbonyls (C=O), and anything else that pulls electron density toward itself.

Leaving Group is Also Important

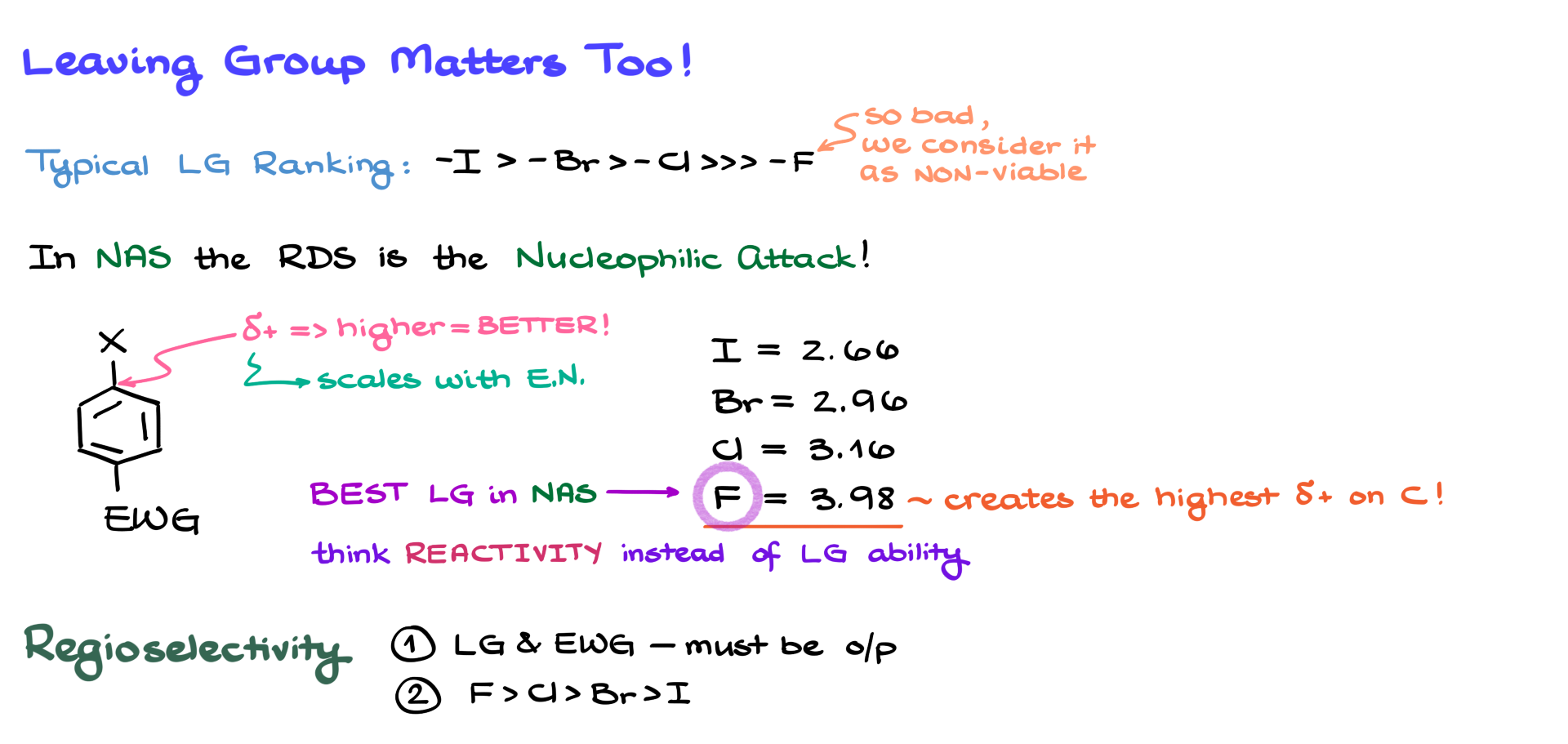

In addition to the placement of the electron-withdrawing group, the nature of the leaving group also matters. Normally, when ranking leaving groups, we think of iodine as the best, followed by bromine, then chlorine, with fluorine being such a poor leaving group that we usually don’t even consider it. However, in nucleophilic aromatic substitution, the key factor to keep in mind is that the rate-determining step is the nucleophilic attack itself.

To understand why fluorine works as a leaving group here, let’s look at the periodic table and examine electronegativities. Iodine has an electronegativity of about 2.66, bromine is 2.96, chlorine is 3.16, and fluorine is nearly 4.0. Because fluorine is the most electronegative, it induces the strongest partial positive charge (δ⁺) on the carbon it is attached to. A higher δ⁺ makes the carbon more electrophilic and more reactive toward nucleophiles. So, despite being a poor leaving group in most cases, fluorine is actually the best leaving group in nucleophilic aromatic substitution. Instead of thinking about leaving groups in terms of their ability to leave, we should think about them in terms of how much they activate the carbon toward nucleophilic attack.

So, when considering regioselectivity in nucleophilic aromatic substitution, the first thing to check is the position of the leaving group relative to the electron-withdrawing group—they must be ortho or para. If there’s still a choice to be made, fluorine is the best leaving group, followed by chlorine, then bromine, and finally iodine if no other options are available.

Example 1

Now that we have the theory down, let’s apply it to some practice problems.

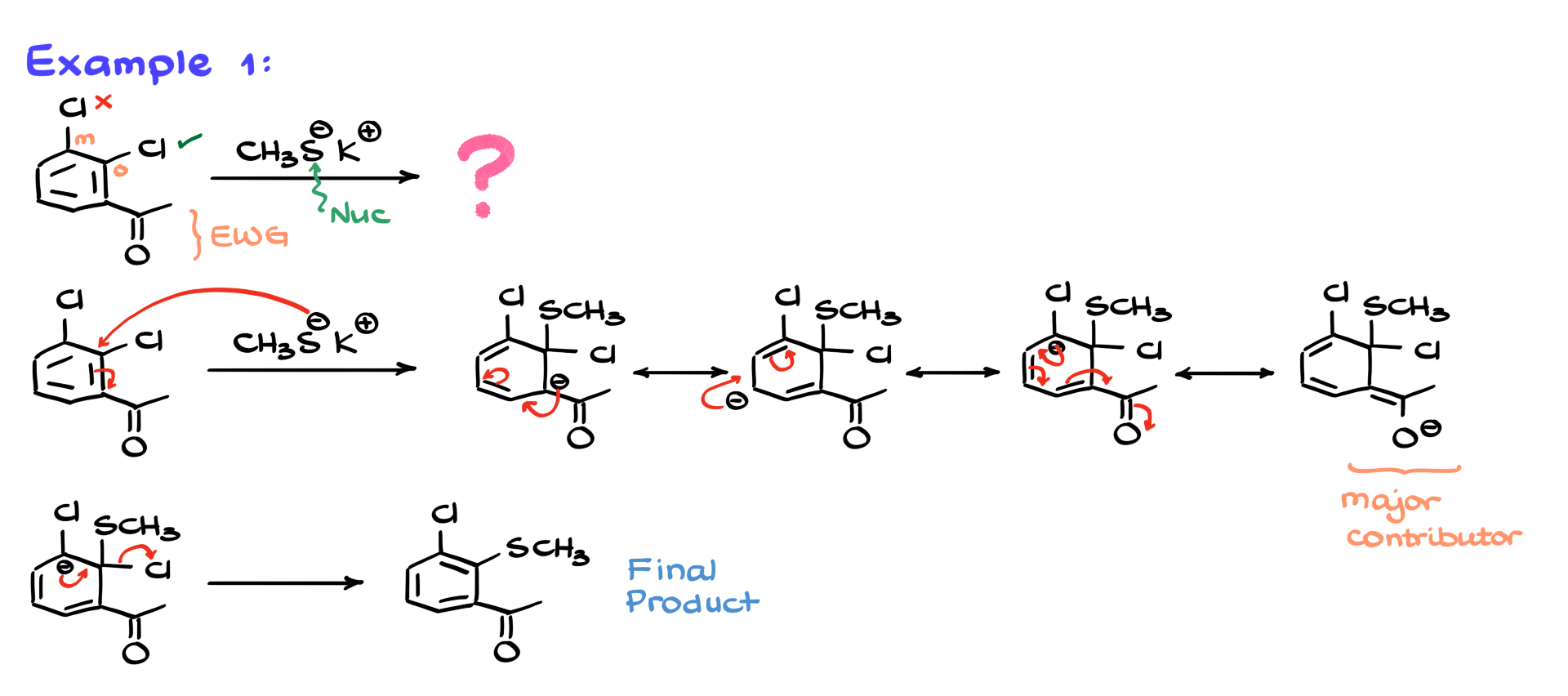

Here’s the first example. I have a molecule with a carbonyl group, which is a typical electron-withdrawing group, and two chlorines. One chlorine is ortho to the electron-withdrawing group, while the other is meta. This means that only the ortho chlorine is useful for the reaction. The nucleophile in this case is a sulfur-containing species.

To draw the mechanism, I start by redrawing the molecule. First, the sulfur attacks the carbon attached to the chlorine, pushing electrons into the ring. This creates a negatively charged intermediate. Several resonance structures can be drawn, just like before. The major resonance contributor has the negative charge on the oxygen, stabilizing it. Next, we move on to the elimination step, where the electrons shift back to kick out the chlorine, yielding the final product.

Example 2

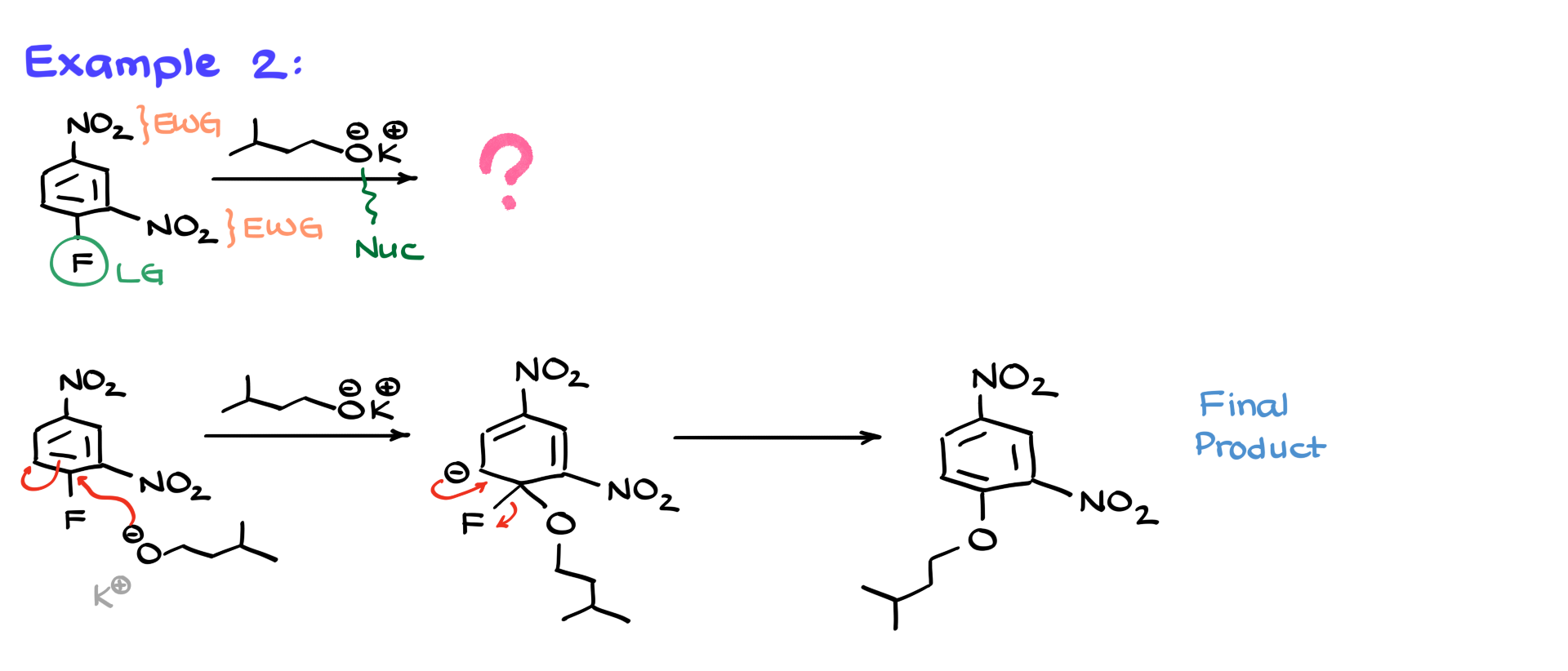

Let’s move on to the next example.

This molecule has two nitro groups, meaning it has even stronger electron-withdrawing effects. We also have fluorine as the only leaving group, and the nucleophile is an oxygen-containing species (an alkoxide). Following the same process, I redraw the molecule and show the nucleophilic attack. Again, multiple resonance structures form, but for the sake of time, I won’t draw them all. The elimination step then kicks out the fluorine, producing the final product. This is a textbook example of nucleophilic aromatic substitution because the strong electron-withdrawing groups and an excellent leaving group make the reaction extremely fast.

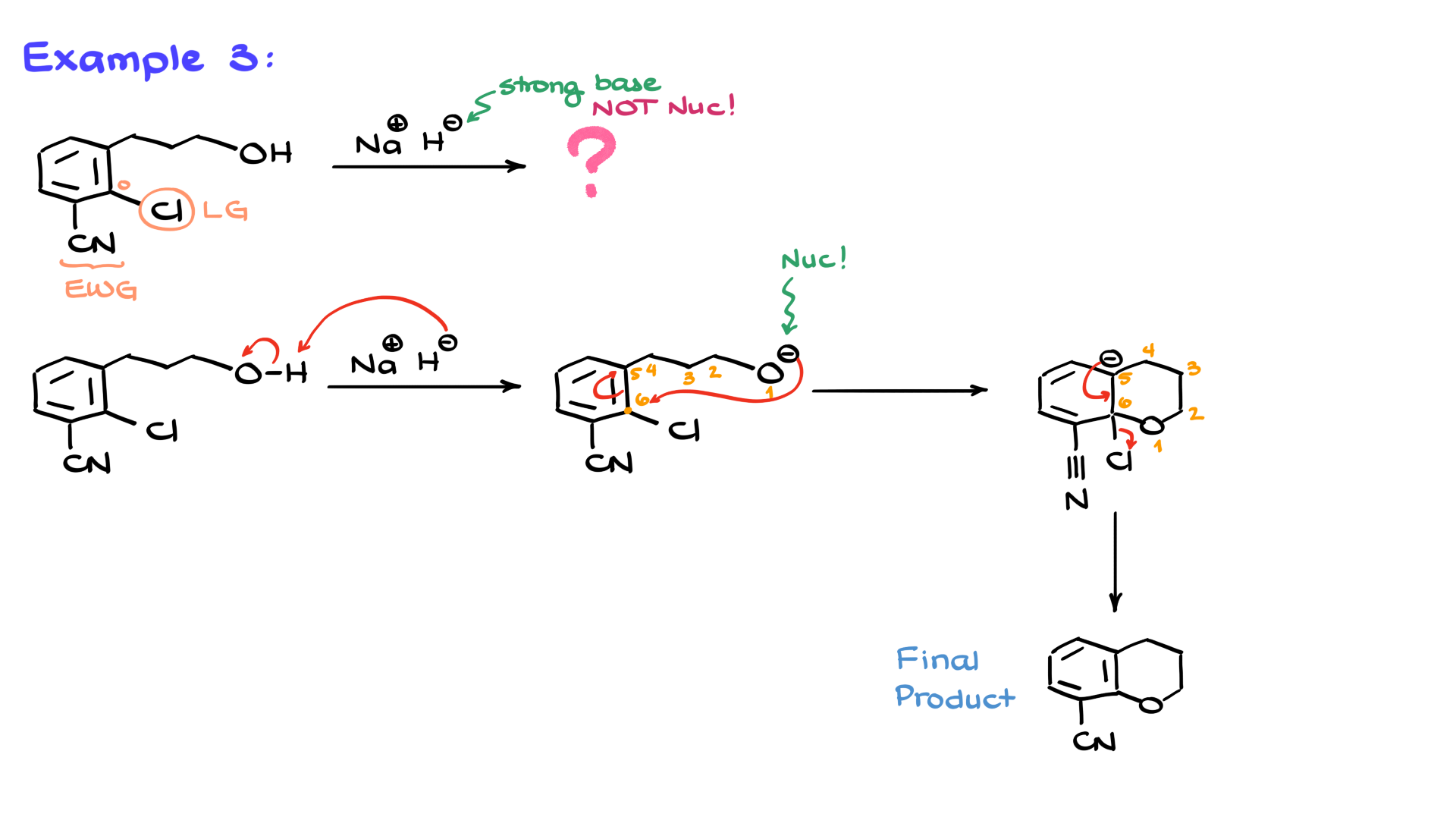

Example 3

Now, let’s look at one more interesting case.

This molecule features a large aromatic system and sodium hydride as the reagent. But here’s the twist—hydrides are strong bases but poor nucleophiles. So, what’s happening here? Looking at the molecule, we see a leaving group (chlorine) and an electron-withdrawing group positioned correctly. Everything seems favorable except for the nucleophile.

To solve this, I start by redrawing the molecule. Since hydride is a strong base, it can deprotonate the oxygen, generating an alkoxide nucleophile. And since I know how much you all love intramolecular reactions, here’s a nice cyclization for you. The oxygen now attacks an electrophilic carbon in the ring, forming a six-membered ring. This produces another negatively charged intermediate, which undergoes resonance stabilization. Finally, in the elimination step, the electrons shift back to expel the chlorine, yielding the final cyclic product.

That’s it for nucleophilic aromatic substitution! Hopefully, these examples help clarify the mechanism and key factors that influence the reaction. Now, let’s move on to some more practice questions!

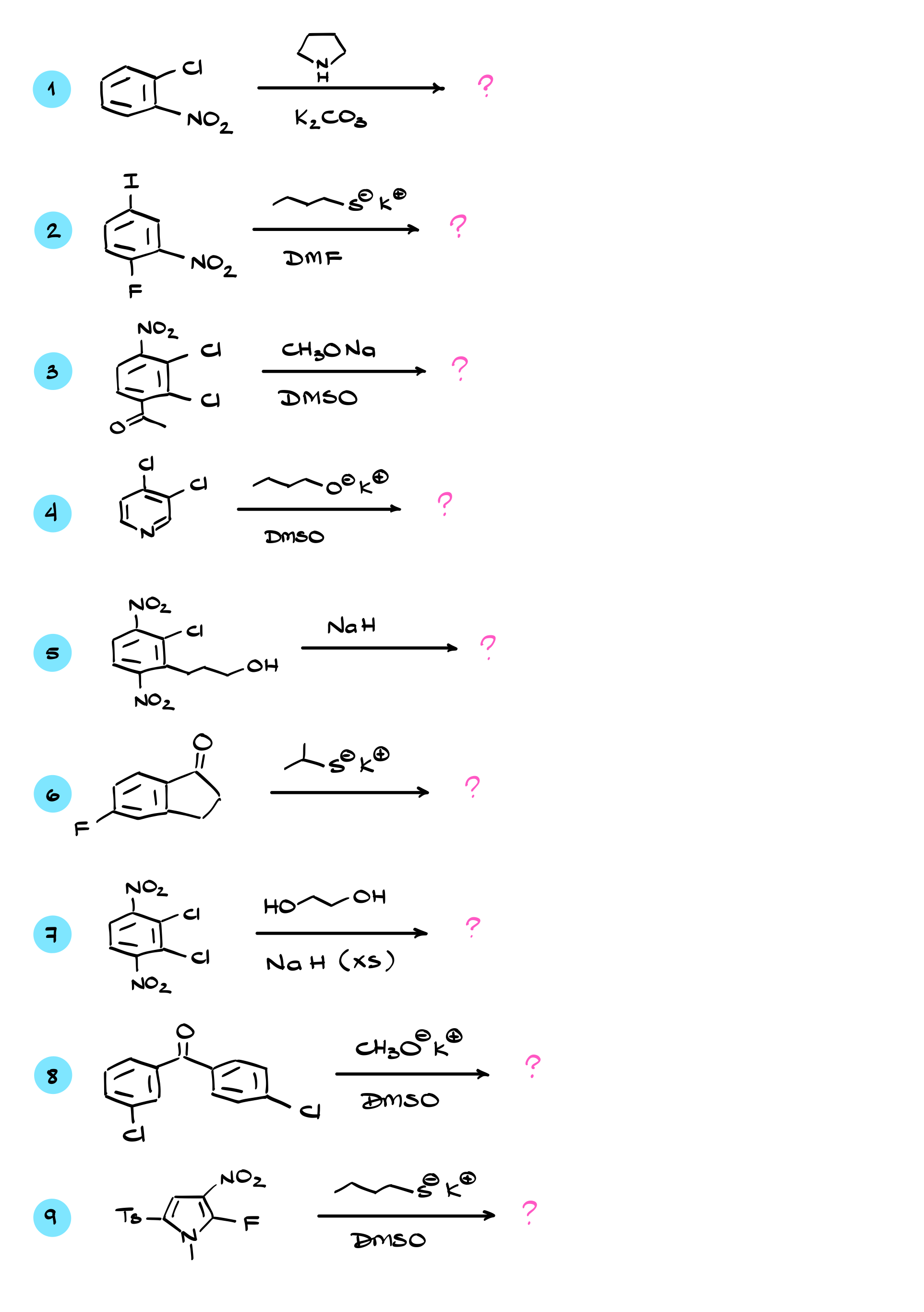

Practice Questions

Would you like to see the answers and check your work? Become a member today or login if you’re already a member and unlock all members-only content!