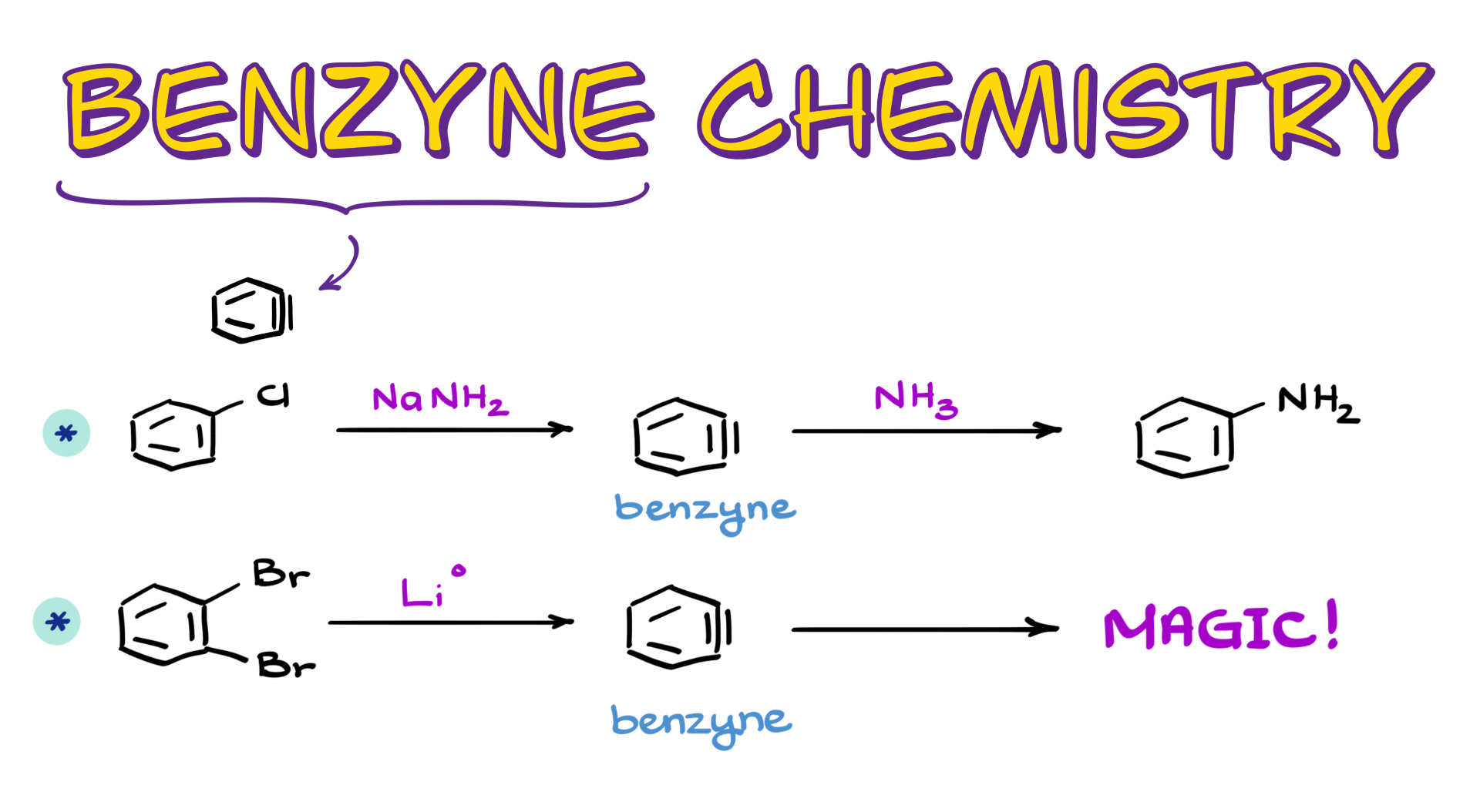

Benzyne Chemistry

In this tutorial, I want to talk about a rather interesting reaction intermediate called benzynes, which look like benzene with a triple bond. Of course, there isn’t a real triple bond there, but this intermediate is well-described and well-investigated. However, the exact structure of this intermediate goes beyond the scope of this tutorial.

Typically, we see benzynes as intermediates in nucleophilic aromatic substitution reactions, but there are other methods to generate these exotic species. So, let’s talk about these fascinating intermediates, starting with nucleophilic aromatic substitution reactions.

Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution (Elimination-Addition)

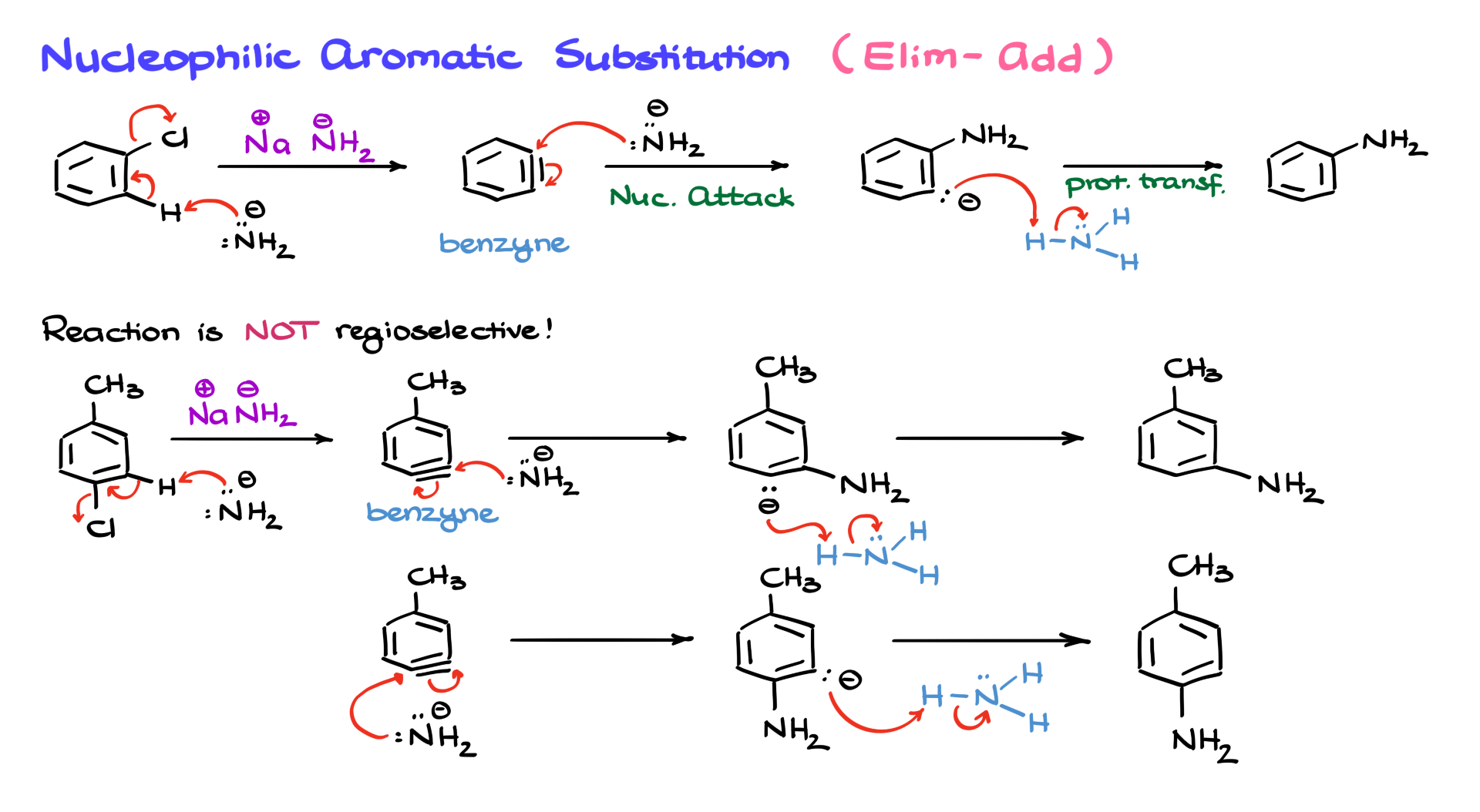

When it comes to nucleophilic aromatic substitution, I have another tutorial where I discuss the addition-elimination mechanism. In this tutorial, we’re going to focus on the elimination-addition mechanism.

Essentially, we start with an aromatic compound containing a leaving group—typically chlorine or bromine—and treat it with a very strong base/nucleophile. Since, in this case, we don’t have a powerful electron-withdrawing group to stabilize the negatively charged intermediate, the usual nucleophilic aromatic substitution mechanism won’t work. Instead, we use an amide base to deprotonate the position adjacent to the leaving group, generating the benzyne intermediate.

But that’s not the end of it. Benzynes are incredibly unstable and highly reactive. They typically act as very strong electrophiles. Since we are working in the presence of an amide, which is a nucleophile, the nucleophile can react with one of the carbons in the so-called triple bond, pushing the electrons onto the other carbon. This results in an intermediate with a negative charge on the aromatic ring. At this point, we introduce the conjugate acid formed in the first step, which protonates our intermediate, yielding the final product—an aniline molecule.

Regioselectivity in Benzyne Reactions

While this reaction seems fine on paper, it has a major issue: regioselectivity. The reaction is not regioselective. Let me explain what I mean.

Consider the molecule pictured in the scheme above, p-chlorotoluene. If we carry out the same reaction with sodium amide, the first step involves proton transfer, leading to the elimination that generates the benzyne intermediate. From here, the amide nucleophile can attack the benzyne, forming an intermediate that, after proton transfer from ammonia, yields m-methylaniline.

However, the key point here is that the benzyne intermediate allows for nucleophilic attack at two different positions. Instead of reacting at one site exclusively, the nucleophile can also attack from the other side, leading to a second intermediate. After proton transfer, this results in p-methylaniline. Consequently, instead of obtaining one clean product, we end up with roughly a 50-50 mixture of two constitutional isomers, which is far from ideal for synthetic applications.

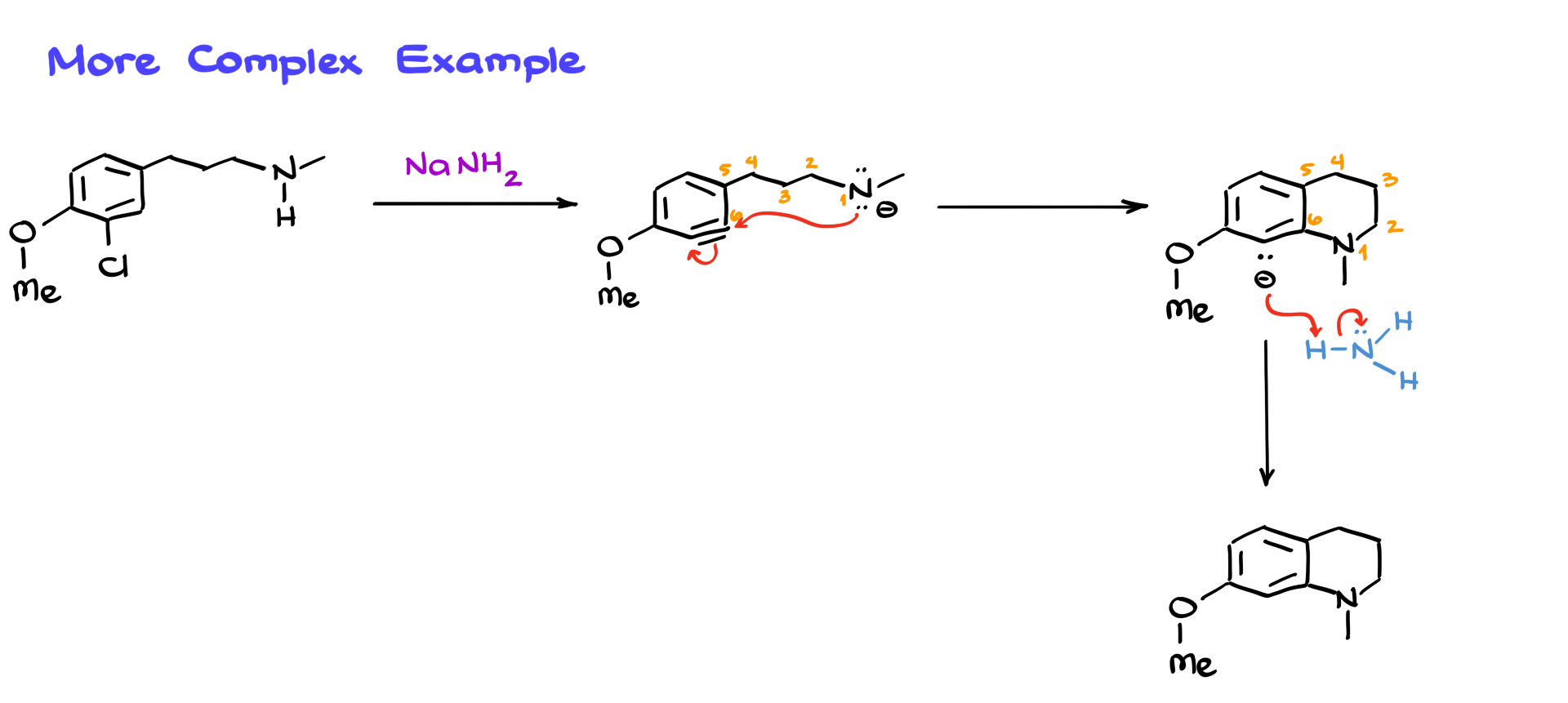

That said, this reaction can still be useful in cases where regioselectivity is not a concern or when only one pathway is possible. Let’s look at a slightly more complex example. Here, we have a molecule with multiple functional groups, including chlorine as our leaving group. When we treat it with sodium amide, elimination occurs as before, leading to the formation of the benzyne intermediate. However, in this case, the nitrogen nucleophile can only attack one specific position due to steric constraints. This results in the formation of a six-membered ring. Because there’s only one possible reaction pathway, we obtain a single major product.

While the nucleophilic aromatic substitution via the benzyne intermediates can be useful, it does have limitations. Using harsh bases like sodium amide or requiring high temperatures—such as when using hydroxide as a base at around 200°C—can be problematic. Many organic molecules are not stable under such conditions. Fortunately, there are alternative methods to generate benzynes that do not require extreme conditions.

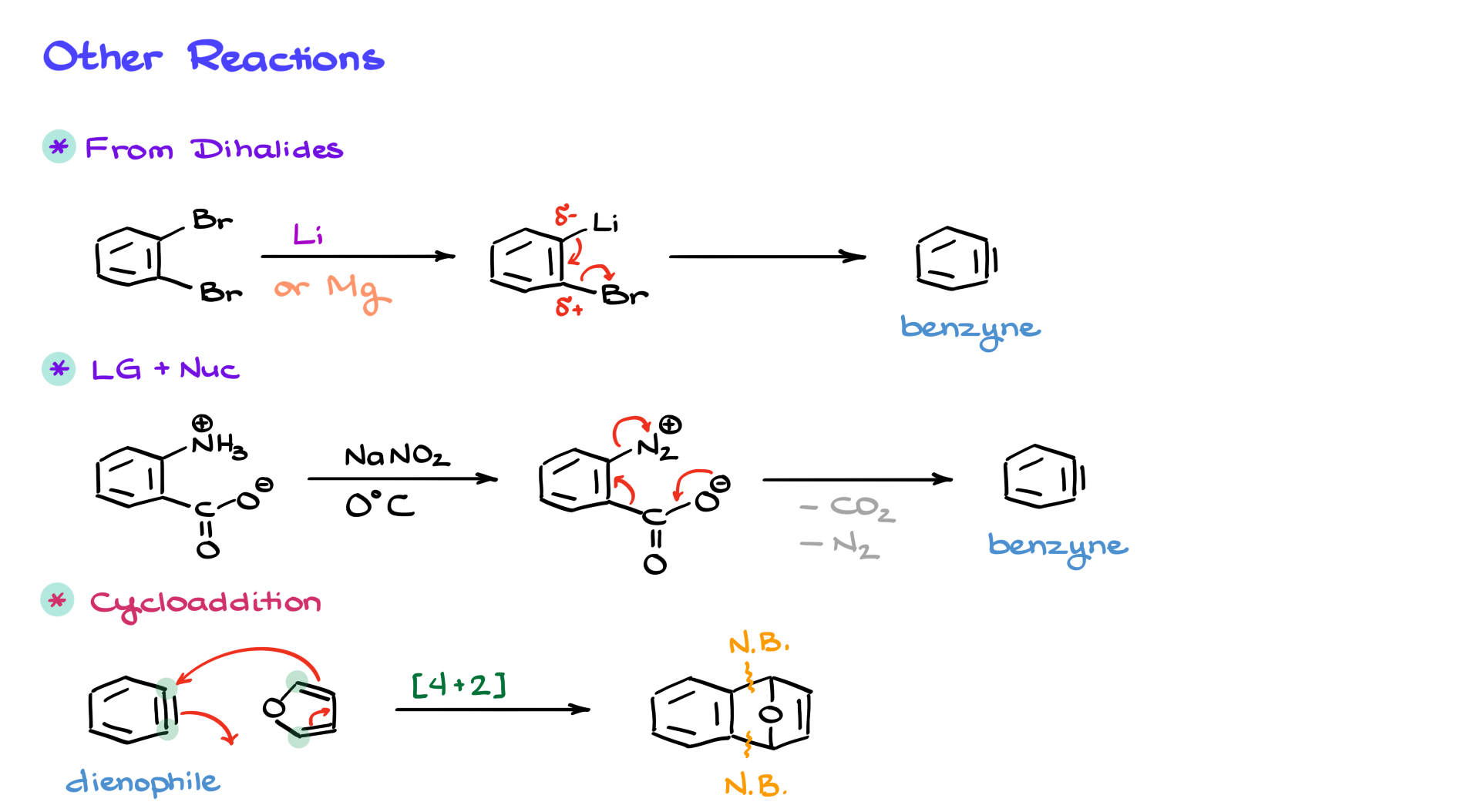

Other Methods of Benzyne Generation

One of the most common methods involves dihalides. For example, if we start with an ortho-dibromide and treat it with lithium or magnesium, we first form the corresponding organometallic compound. However, these organometallic intermediates are not very stable due to the close proximity of a strong nucleophile (the organometallic species) to an electrophilic leaving group. As a result, the system undergoes elimination, expelling the leaving group and generating the benzyne intermediate. This approach allows for benzyne formation under much milder conditions compared to using strong bases or high temperatures.

If organometallic reagents are not desirable, another elegant approach involves diazo compounds and carboxylic acids. One of my personal favorites, which I’ve used many times in the lab, involves ortho-aminobenzoic acid. We first convert the amine to a diazo group via a standard diazotization reaction with sodium nitrite, forming a diazonium intermediate. At this stage, we have a system similar to before, where we have a good leaving group (N2), a nucleophile (the carboxylate), and an electrophilic carbon adjacent to the leaving group. The carboxylate donates electron density, facilitating the elimination of both CO2 and N2, generating the benzyne intermediate under very mild conditions.

Once we have benzynes, they can participate in a variety of interesting reactions. One of my favorites is the cycloaddition reaction. In addition to being strong electrophiles, benzynes are also excellent dienophiles. For example, if we introduce benzynes to a diene, such as furan, they readily undergo a Diels-Alder reaction. This results in the formation of a new tricyclic system, with two newly formed bonds connecting the diene to the benzyne. Pretty cool, right?

While benzynes can participate in many different reactions, the key reaction you need to remember for most courses is nucleophilic aromatic substitution via the elimination-addition mechanism. And the most important takeaway? This reaction is not regioselective, which can be a significant limitation.