CIP Rules and R/S Stereodescriptors

In this tutorial we are going to look at the R and S stereodescriptors and how to use the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog priority rules to assign those. First, let’s look at these couple of molecules.

These two molecules (compound 1 and compound 2 ) are two completely different molecules. Using the technical terms: these molecules are stereoisomers; enantiomers to be exact. We are going to talk about those in one of the next tutorials, but for now let’s focus on how to name them.

Why do we care so much about naming them? Well, the problem is—if we have each of those compounds in a separate bottle on a shelf—how are we going to label them? One way would be to use the pictorial form and just draw a corresponding structure on a label. This method is, however, not very useful and has some serious limitations.

Historically, there have been several different ways of describing the molecular stereochemistry. The major problem with those methods was the lack of a unified rule system. This problem has been solved by the three chemists:

- Robert Cahn (British)

- Sir Christopher Ingold (British)

- Vladimir Prelog (Croatian-Swiss)

Nobel Prize in 1975 for his research in stereochemistry

The foundations of the system appeared in the 1966 paper by Cahn and Ingold. Later, the system has been further systematized in a 1982 paper by Prelog who prior to that received the Nobel Prize for his research in the field of stereochemistry in 1975. Nowadays, we know this system as the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog Priority Rules, or CIP rules for short.

CIP Priority Rules

Before we dive any further, I want to make a small remark. The CIP rules are used for most but not all types of the stereodescriptors. Within the scope of a typical introductory organic chemistry course, we will only look at the R/S and E/Z stereodescriptors that use the CIP system. Later in the course (typically in the second semester), you’ll learn about the D/L stereodescriptors which are commonly used in glycochemistry (chemistry of carbohydrates).

The CIP rules are based on the group priorities. Group priorities only make sense in relation to each other. A group priority in an isolation when you’re not comparing it to another group is quite meaningless.

First and most important rule is:

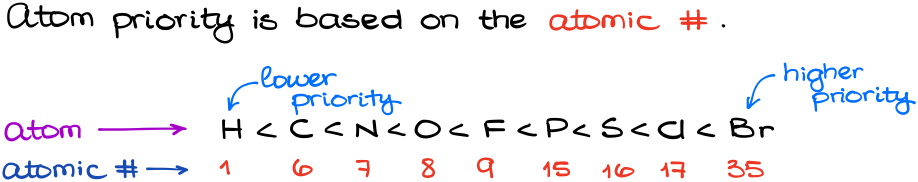

Atom priorities are assigned based on the atomic number. There are a lot of misconceptions and misinformation out there. It’s not atomic mass, or electronegativity, or a group size, or anything else. It’s the atomic number that matters.

Thus, here is what we get for the most common elements in organic chemistry:

So, does the atom mass matter at all? And the short answer is yes, it does. If we compare different isotopes, then we compare their masses. The heavier isotope has a higher priority. This is the ONLY time when the atomic mass matters. Thus:

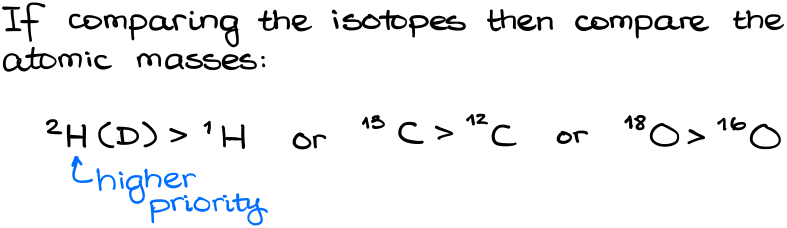

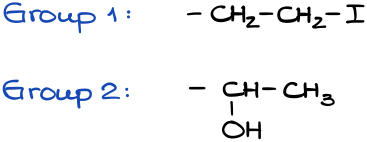

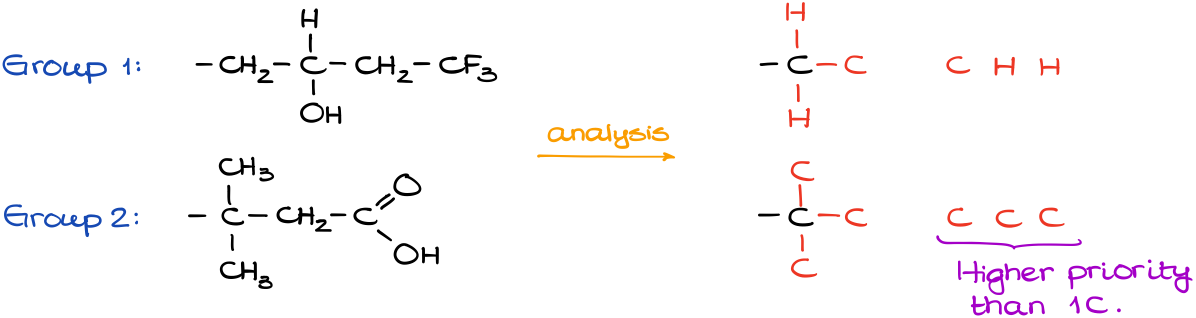

If we have the same atom, then we need to compare the next atom along the chain until we find the first difference. Let’s look at a couple of examples here:

Since the first atom in each group is a carbon (C), we need to look at the next atom along the chain:

In Group 2, we have an oxygen vs carbon and hydrogens from Group 1. This is the first difference between the groups, and this is the only difference that matters. When analyzing the groups to assign the priorities, we always look for the very first difference and once we find it, we ignore it for the rest of the group completely.

Here’s another example:

Once we do a layer-by-layer analysis of these two groups, we quickly see that in the group 2 we have 3 C’s vs only one C in group 1. While the priority of the carbon atom is the same in both cases, we have more carbons in group 2 than in group one. This gives the group 2 a higher priority overall. Notice, just like in the previous case, here we stopped as soon as we found the first difference. The rest of the group is completely irrelevant for the purposes of the CIP rules and the group priority determination.

Traditionally, the highest priority group is given #1 while the lowest priority group is given #4. This is the convention you’re going to see in your textbook, and we will also use this priority in any kind of standardized exam. So, make sure you remember that 1=high and 4=low.

Alright, we have determined the priorities of all the groups, now what? At this point we are ready to assign the stereodescriptor to the atom containing the four different priority groups.

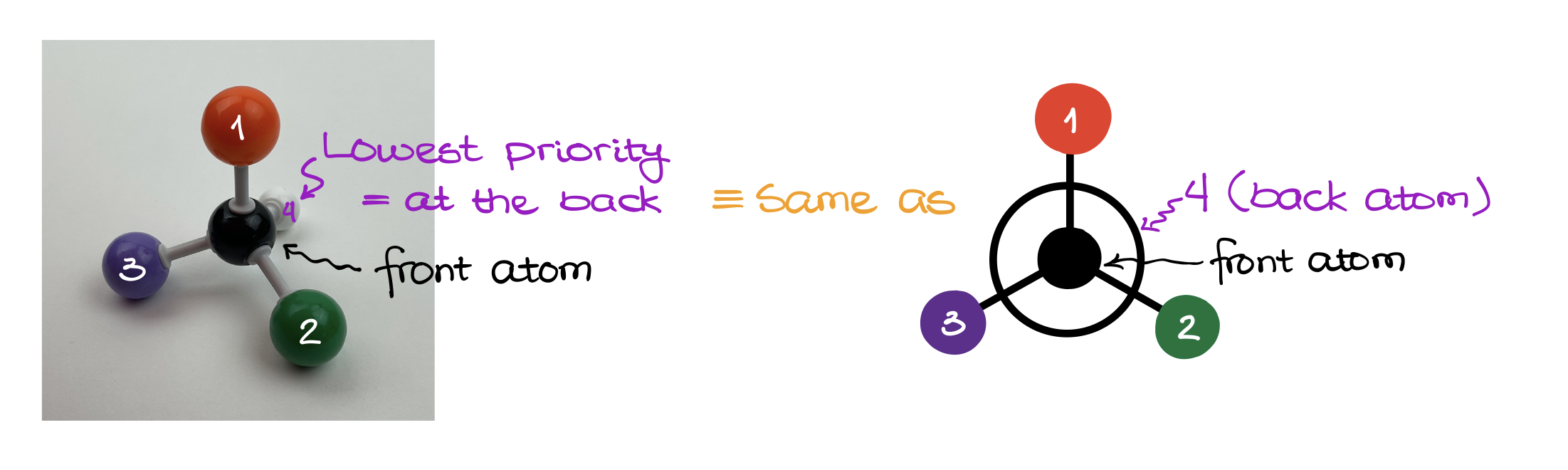

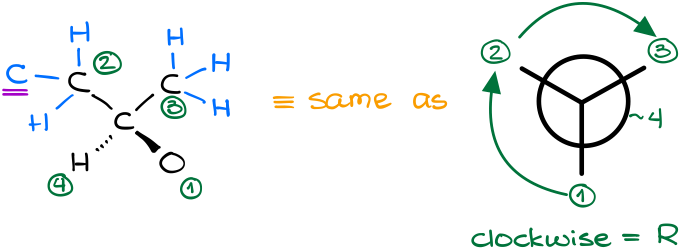

According to the CIP rules, to assign the stereodescriptor, we need to make sure that the lowest priority group (#4) is oriented away from the observer. In other words, the #4 must be in the back. Then, we check how the rest of our groups are oriented in space.

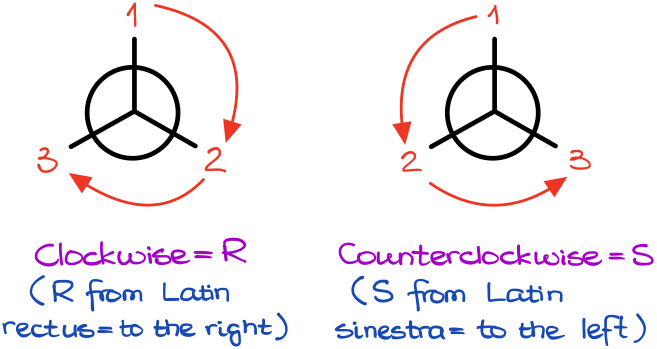

Using the Newman Projections here is, probably, the easiest way of looking at the molecule correctly. And once we reorient molecule and look at it, the group priorities can either follow the clockwise pattern or the counterclockwise pattern.

The clockwise arrangement corresponds to the R-stereodescriptor (from Latin rectus = to the right) and the counterclockwise arrangement corresponds to the S-stereodescriptor (from Latin sinestra = to the left).

Now, when we know the rules, let’s look at a few examples here.

Example 1:

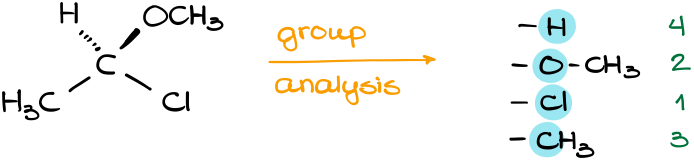

In this example our carbon of interest in connected to four other groups. Since each group is obviously different, we have a chiral carbon and can assign the R or S stereodescriptor to it. Overall, this example is quite straightforward. By quickly checking our groups, we see that they all have a different atom on the very first “layer” of the group. Thus, we just need to compare those first atoms.

As our groups follow the counterclockwise pattern, this molecule is the S-isomer.

Here’s another example. Assign the stereodescriptor to the highlighted atom:

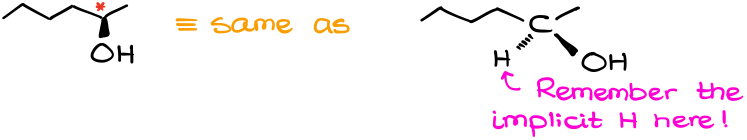

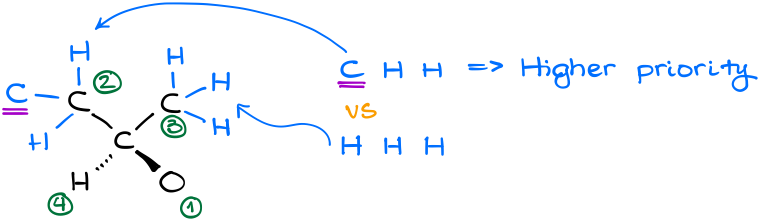

In this example, our carbon of interest is connected to two carbon-containing groups, a hydrogen, and an alcohol (-OH) group. The decision for the oxygen and hydrogen atoms are quite easy. Oxygen has the highest atomic number, so it gets #1, hydrogen has the lowest atomic number, so it gets #4. Carbon-containing groups, however, will require further analysis.

By analyzing our carbon-containing groups, we can see that in the second “layer” or order of connectivity, we have CHH vs HHH atoms. Thus, the group on the left gets the priority.

Since the groups in this molecule follow a clockwise arrangement, this is the R-isomer.

What to do if the lowest priority is not at the back?

Up to this point we’ve only seen examples in which the lowest priority group was looking back. But what if it is not? How are we going to deal with the molecule then? Of course, you can make the molecule out of your molecular model kit or try to imagine it in 3D and then just rotate it around. However, making a molecule from a molecular model kit is time consuming and 3D imagination is not a human’s native skill, so it’s hard to do. Luckily, there’s a simple trick to it.

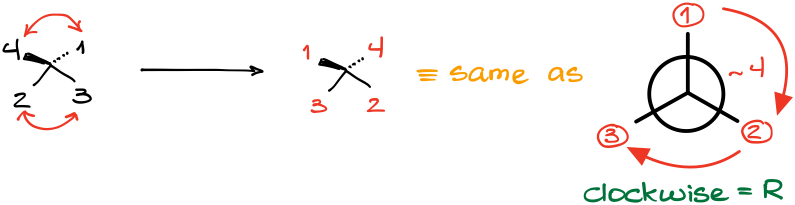

While there are many “tricks” out there, probably the easiest one and the most “foolproof” method is what I like to call a “double flip” method. In a nutshell, if you have a molecule where the lowest priority atom is NOT facing away, you can exchange the positions of two pairs of groups (flip them) at the same time. This creates the same molecule but rotated in space. Let me illustrate this with an example:

After assigning the group priorities in this molecule, we can see that the lowest priority is not facing away from us. So, here’s how the double flip works:

- Redraw just the stereocenter with the priority numbers, but don’t draw the actual groups.

- Exchange the position of two pairs of groups at the same time making sure that the #4 ends up looking away (on the dash).

The result of the flip is the same molecule but rotated in space along one of the axes. This method is generally easier than imagining the molecule in 3D, especially at the beginning when you are only developing your 3D skills.

Now, when you’ve got the basic skills and know how to assign the R and S stereodescriptors, make sure you work through plenty of practice problems. You want to practice to the point when you can assign the stereodescriptors quickly and correctly. While the CIP rules are going to be on the exam right after you cover this topic in your class, this is nothing more than a useful instrument for the future. So, you need to make sure you can assign the R and S stereodescriptors quickly.

CIP Rules for Heteroatoms

Can we only assign the R/S stereodescriptors to carbons? No! Other atoms can have the stereodescriptors as well! In the previous tutorial we talked about the basic rules of how we assign the R and S stereodescriptors to simple molecules. Here, I want to talk about those cases when instead of a carbon atom we have a heteroatom such as S, N, P, etc.

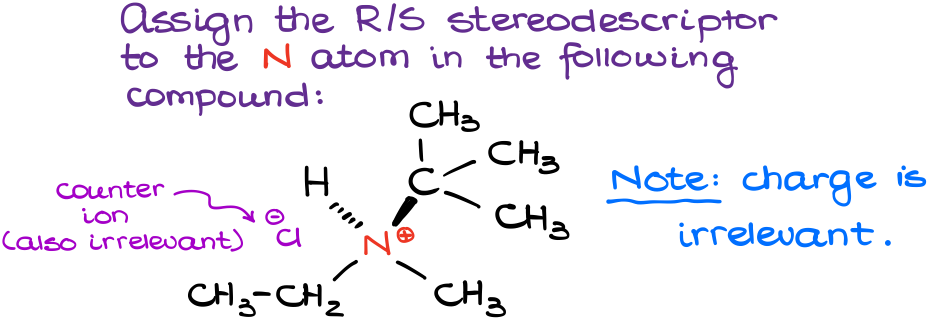

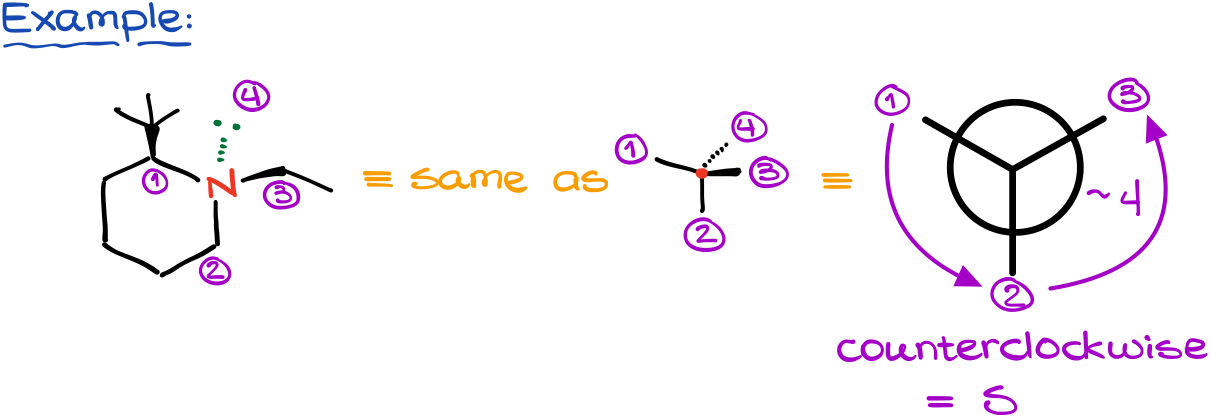

Let’s look at this molecule here:

In this molecule we have a nitrogen atom (N) connected to four different groups. And, if an atom is attached to four different groups, it is chiral. Thus, we can assign a corresponding stereodescriptor to it. Notice, that a formal charge or any counter ions that might be present are completely irrelevant for our analysis. We will only consider what is actually bound to nitrogen.

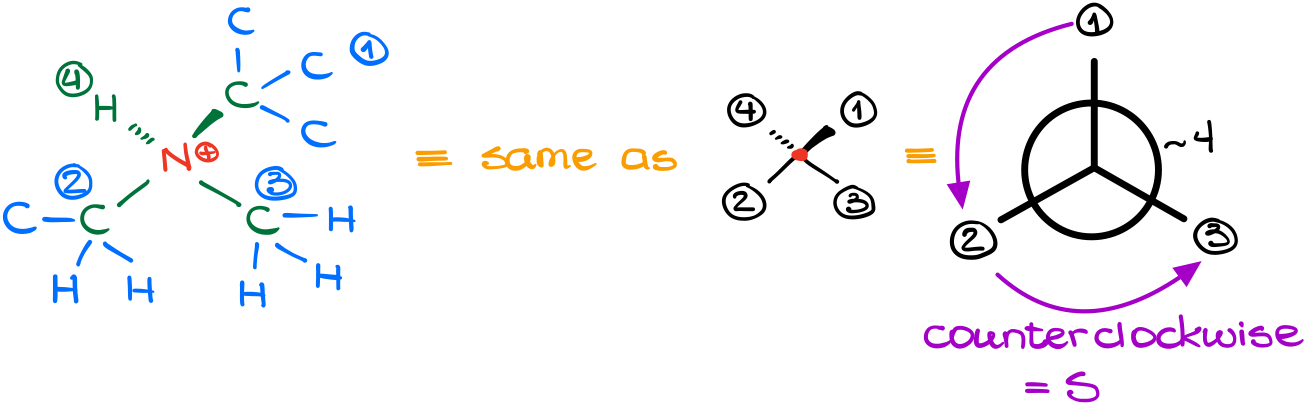

Doing a layer-by-layer analysis the way we’ve learned in the last tutorial, we can easily assign priorities to our groups.

As the lowest priority group is facing away from us, we can assign the stereodescriptor right the way. In this case, it is the “S” isomer.

What if we have an electron pair?

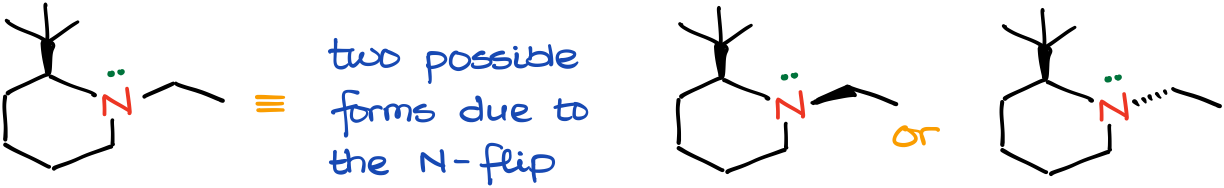

Most heteroatoms contain non-bonding electron pairs. Due to the quantum channeling through the atom, the electron pair can flip-flop thus making any conversation about the stereochemistry of such atoms useless. However, this is not always the case. We can have molecules where the “flip” is difficult due to some steric restraints.

For instance, in the molecules above, we have a bulky tert-butyl group which makes it unfavorable for the ethyl group on the nitrogen to stay on the same side of the molecule where the t-butyl group is. By having both substituents in an equatorial position, the molecule achieves the lowest energy, and thus, highest stability.

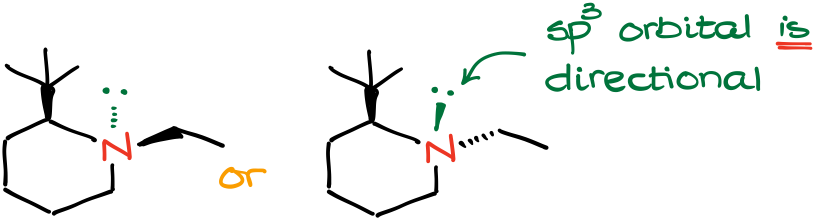

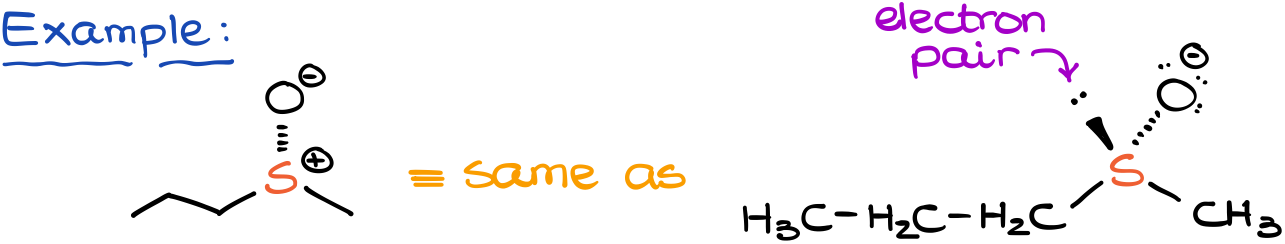

As the electron pair is sitting on the sp3-hybridized orbital, it is directional. For the simplicity of the representation, we can put the electron pair on a “bond” as if it is a substituent of its own.

Now, we can assign our priorities. The electron pair has the lowest possible priority. This means that it is even lower in priority than a hydrogen atom.

This way, when we assign our priorities, we can proceed as usual with our stereodescriptor assignments.

Beware of the implicit electron pairs!

Here’s something important: in organic chemistry we often omit the electron pairs when we draw our structures. However, just because we didn’t show them, doesn’t mean they are no longer there! So, always check for the implicit electron pairs in the molecule before doing any kind of stereochemical analysis. For instance:

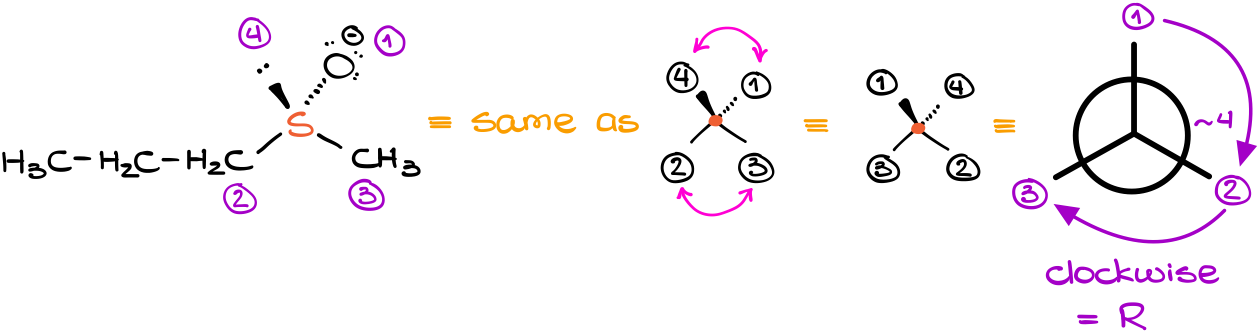

In this molecule we have sulfur seemingly connected to only three groups. This is in actuality is not correct because there’s an implicit electron pair on the sulfur atom. And as the oxygen atom is oriented away from the observer, it means that the electron pair must be looking at us. This brings additional complication because we no longer have the lowest priority group conveniently pointing away from us.

After assigning the priorities like we would normally do remembering to give the electron pair the lowest priority, we can then use the “double-flip” method to reorient the molecule in space. By doing so, we can easily assign the stereodescriptor to our molecule. This molecule is an “R” isomer.