Grignard Reaction of Epoxides

In this tutorial, I want to talk about the Grignard reagent reacting with epoxides.

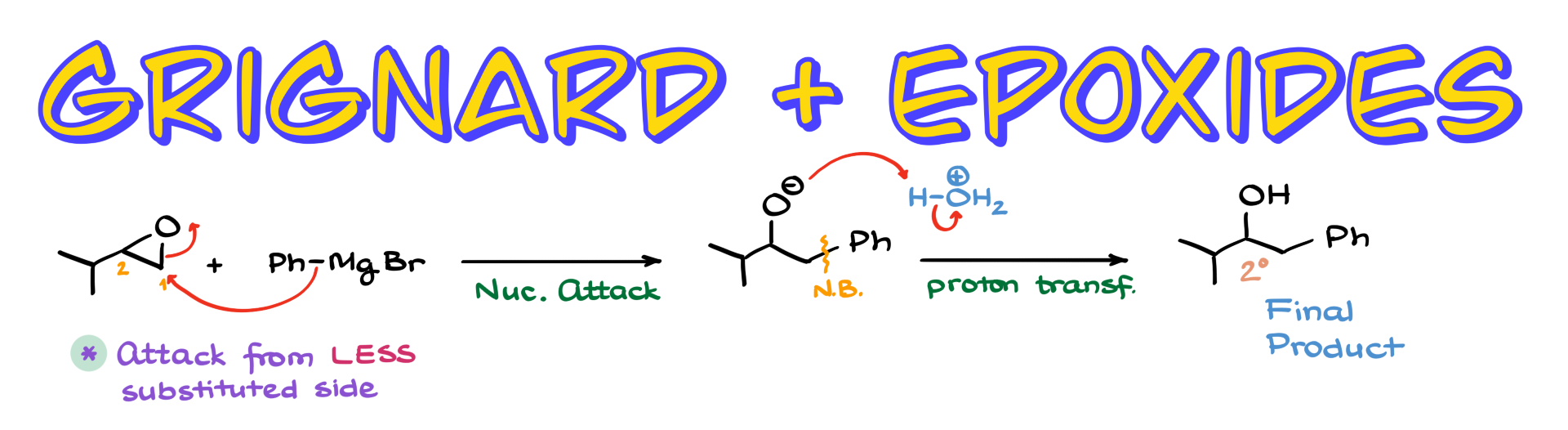

Let’s start with a simple example. Suppose we have an epoxide, and we’re reacting it with phenylmagnesium bromide. This reaction follows a typical epoxide opening mechanism with a strong nucleophile, and in such cases, the attack happens at the less substituted carbon of the epoxide.

If we number the epoxide carbons as carbon 1 and carbon 2, where carbon 1 is the less substituted one, our nucleophile will attack this position. Mechanistically, phenylmagnesium bromide attacks carbon 1, breaking the C-O bond, resulting in an intermediate where a new carbon-carbon bond has been formed.

Since this is a Grignard reaction, we follow up with an aqueous workup. The acidic workup protonates the negatively charged oxygen, yielding our final product, which is a secondary alcohol in this case.

Simple enough, right? Well, let’s look at another example.

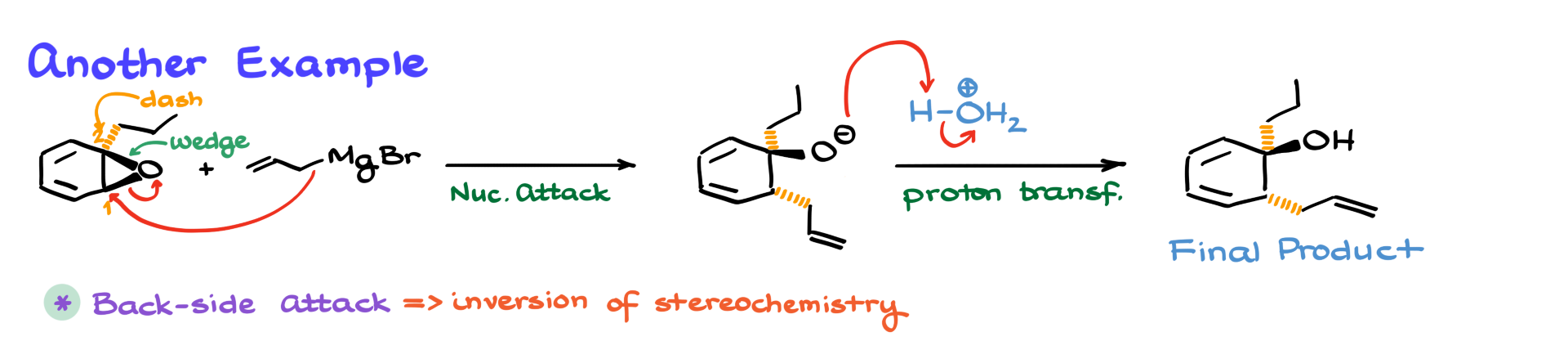

This time, our epoxide is reacting with vinylmagnesium bromide, another Grignard reagent. As before, we number the epoxide’s carbons as 1 and 2, and since carbon 1 is less substituted, that’s where our nucleophile attacks. The vinyl group from the Grignard reagent opens the epoxide at carbon 1, breaking the C-O bond and forming a new carbon-carbon bond.

Again, after the acidic workup, we obtain our final alcohol product. The new bond that was formed is now part of the product structure.

Stereochemistry Considerations

One important thing to remember when opening epoxides under basic conditions (such as with a Grignard reagent) is stereochemistry.

Since this reaction follows an SN2-like mechanism, we always see a backside attack, leading to inversion of configuration at the attacked carbon.

For example, if we start with a chiral epoxide, where a substituent is on a wedge or dash, the product will have the newly introduced group in the opposite direction. So, if the epoxide had a substituent pointing forward (on a wedge), after the Grignard attack, the new group would be positioned backward (on a dash) and vice versa.

Application in Synthesis

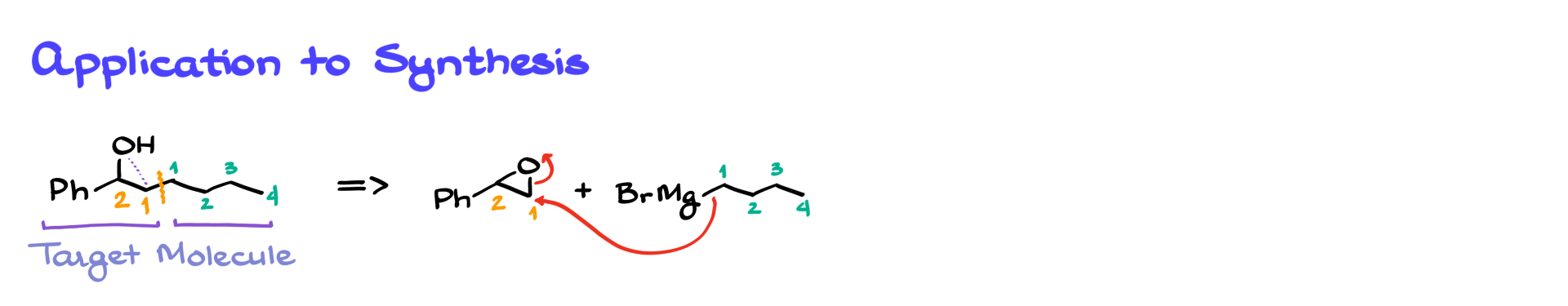

The Grignard reaction with epoxides is particularly useful in organic synthesis because it allows us to form carbon-carbon bonds, which is a key goal in many synthetic strategies. Let’s consider a target molecule and see how we can plan its synthesis using an epoxide and a Grignard reagent.

Suppose we need to synthesize a specific secondary alcohol, and we are determined to use an epoxide opening reaction with a Grignard reagent to achieve it.

To do this, we work backward using retrosynthetic analysis.

The carbon bearing the hydroxyl group in the target molecule was originally part of the epoxide. The new carbon-carbon bond formed in the reaction comes from the Grignard reagent.

By identifying the bond we formed, we can break the molecule into the corresponding epoxide and Grignard reagent that would react to give the target product.

For example, if we need to form a four-carbon chain extension, we can use butylmagnesium bromide as our Grignard reagent and react it with an appropriately substituted epoxide.

A common mistake students make in these problems is miscounting carbon atoms—either losing carbons or adding extras. To avoid this, always number your carbons on both the starting materials and products to make sure everything adds up correctly. Even if you understand the reaction well, incorrect carbon counting will cost you points on an exam!

Choosing the Best Epoxide for Synthesis

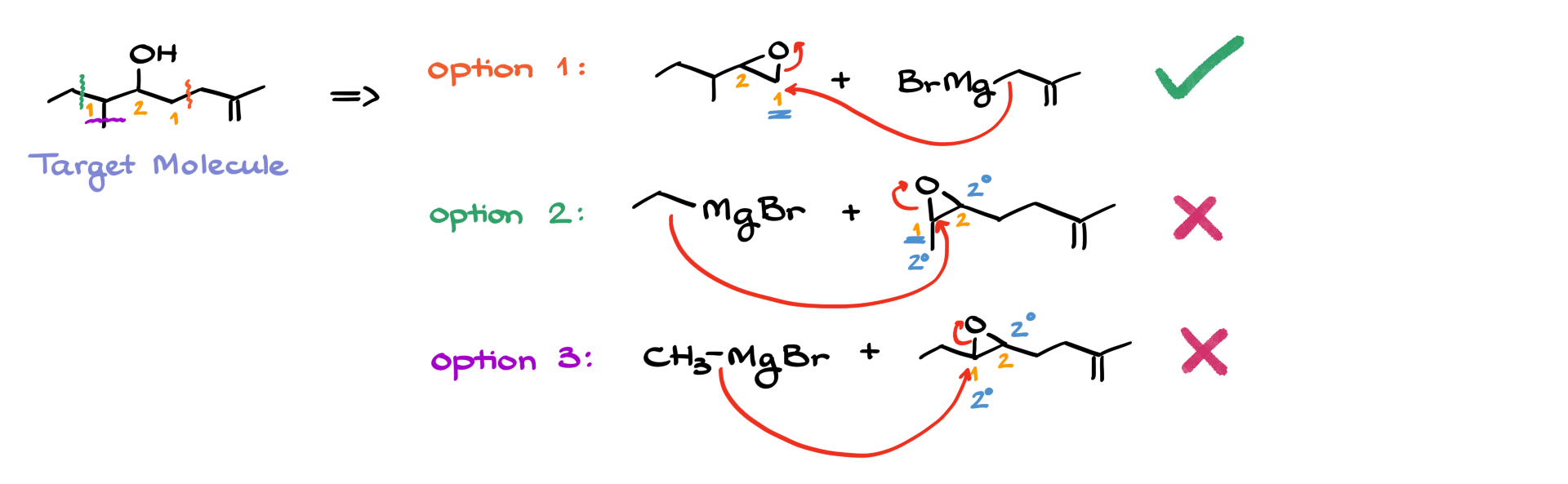

Not every epoxide will give the right product efficiently. Let’s analyze a more complex example where different synthetic options exist.

If we want to make a specific alcohol, we might have multiple choices for how we form the carbon-carbon bond. The epoxide opening can occur at different positions, leading to different possible routes.

For instance, if the target molecule has multiple points where we could form a new bond, we need to evaluate which option gives the best regioselectivity.

- In option 1, we attack the least substituted carbon, which ensures good regioselectivity and a high yield.

- In option 2, we attack a secondary carbon, making the selectivity less reliable.

- In option 3, we attack another secondary carbon, which again leads to poor regioselectivity.

Since options 2 and 3 don’t provide a clear preference for where the nucleophile attacks, they are not ideal. Option 1 is the best choice because it maximizes yield and follows the expected regioselectivity for epoxide openings under basic conditions.

Final Thoughts

While the Grignard reaction with epoxides is a powerful tool in synthesis, it’s not a magic bullet—you always need to carefully analyze regioselectivity and stereochemistry. Not every combination will work, so always check that your epoxide is properly set up for nucleophilic attack at the right position.

So, the next time you’re planning a multi-step synthesis, consider whether the reaction of a Grignard reagent with an epoxide might be a good way to build your target molecule!